Eliza Blue was hard on the eyes, but not in the way Donald Trump thinks that about Carly Fiorina.

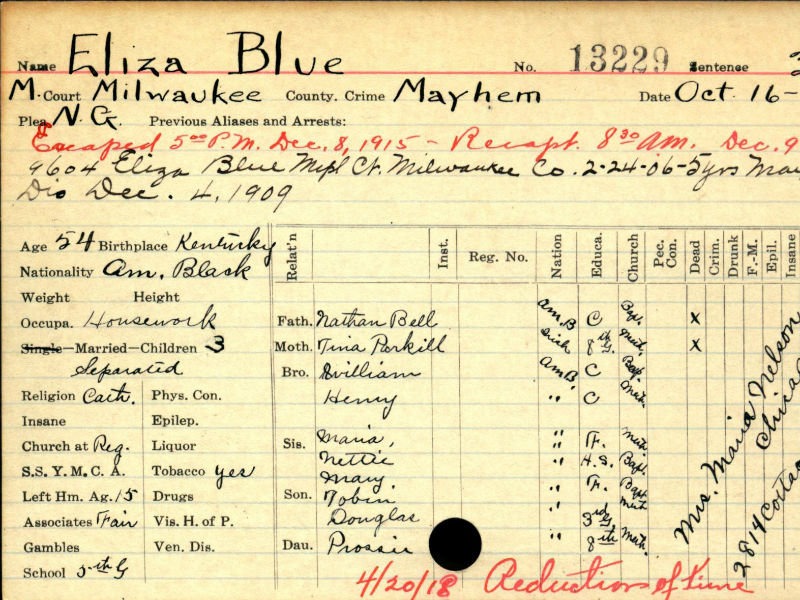

In 1905, the Milwaukee woman permanently blinded a man by throwing acid in his face. Ten years later, Eliza blinded another man the same way.

She was also Milwaukee’s greatest escape artist since Harry Houdini left town. As she was being taken from the courtroom following her second conviction in 1915, Eliza escaped from custody. She was captured, escaped again, was recaptured, escaped a third time, was recaptured again – and, when finally locked up inside the state penitentiary at Waupun, became the only female ever to escape from there.

According to a 1929 newspaper story, before any of the above happened, Eliza Blue was already famous as "the only Milwaukee mother ever to give birth to a son with two heads."

Whether Tobie Blue was actually endowed with two craniums – earlier newspaper stories referred to him as "deformed," "afflicted" and "half-witted" – and whether, as the Milwaukee Sentinel article also reported, he did a brief stint as a circus freak, is uncertain.

But his mother fiercely loved him, and his younger siblings Flossie and Douglas, and that’s why Homer Chavers ended up with a face full of concentrated lye on Nov. 1, 1905.

He and the Blues had separate rooms in a crowded tenement called the "Dove Cote" near 3rd and Wells Streets, then part of the Downtown section known as "The Badlands" for its concentration of black residents, gambling joints and fleshpots.

When Chavers came home and found Tobie Blue in his room, he not very kindly threw the 8-year-old boy out.

"In the colored district Eliza has won a reputation by her battles for her children," the Sentinel reported. "Any remark which she considered derogatory to her babes … transforms the woman, it’s said, into a tigress."

Toby went crying to his mother, she opened a can of lye and pounded on Chavers’ door. Her face was the last thing he saw.

In jail three months awaiting trial for assault with intent to commit mayhem, Eliza was a one-woman "reception committee, general entertainment committee, cheerer of depressed spirits and jester-in-chief," reported the Journal. "(The) women’s ward is a queer conglomeration of the bad, and the half bad and the vicious and the ashamed, and they all look toward black Eliza for relief and amusement. And ‘Liza does not fail them." When a doctor asked if there was anything she needed, Eliza said a prescription for a can of beer would be nice.

At her trial, noted the Journal, she "appeared more like a child, pleased and interested by the novelty of a new experience." Eliza ignored Chavers, sitting with bandages over his disfigured face, and whatever questions she didn’t feel like answering. Her only outward show of concern came before Judge A.C. Brazee sentenced her to Waupun (the state women’s prison at Taycheedah didn’t open until 1933) for five years.

"Please, Judge, I hope you’ll see that my children are taken care of," she said. They went to the Home for Dependent Children.

Though Judge Brazee declared that Eliza’s maximum-allowed sentence was inadequate punishment for breaking "the windows of the soul of (Chavers) forever," and in spite of a couple of bad conduct write-ups for "disobedience, insolence, threats and bad language" at Waupun, she was released from prison 14 months early on Dec. 4, 1909.

And for resorting to lye again to settle an argument with John Gallis when they were drinking in her Badlands apartment on Sept. 26, 1915, Eliza got just three years. But she didn’t count herself lucky until a guard let her take an unsupervised bathroom break after her sentencing, and she found a window open wide enough for her to wriggle out of and commence what Eliza later said was more fun than she’d ever had in her whole life.

Five hundred cops combed the city for her, but she still managed to make it to Mequon and talk her way aboard a northbound train.

Nabbed by a Sheboygan policeman when she got off there, Eliza told him she had a suitcase on the train. The gullible cop went to get the non-existent luggage, and Eliza took off. The next day Police Chief E.N. O’Connell of Plymouth, 14 miles west of Sheboygan, spotted Eliza eating popcorn on a train about to head west and took her off. As they arrived at the police station, reported the Sentinel, Eliza "dashed up an alley, slid in a basement window … lay in a coal bin until they discovered her, and then climbed the stairs of [a] five-story building and got on the roof. The chief fired several shots in the air as she sped away.

"…Finding all adjoining buildings too small for a jump, (Eliza) returned inside and hid in a clothes closet. By this time the building was surrounded by hundreds and the police were inside."

Rooted out of her hiding place, "Milwaukee’s incorrigible colored lady" (Sentinel) was brought back here. The next day, Eliza ostensibly tried to commit suicide by turning on the gas in her room at the jail. But Sheriff Edmund Melms said her real objective was to be taken to the hospital where she could try to escape again.

All of which makes the following sentence from the Journal almost too fantastic to believe:

"The officers did not manacle the woman when they took her to Waupun."

Six weeks later, on Dec. 8, 1915, Eliza became the 65th inmate to escape from there since 1852.

Warden Henry Town and the guards were dumbfounded that their 5-5, 135-pound, 54-year-old prisoner was somehow able to hoist herself up to a window at the top of a 22-foot wall, climb through and drop down on the other side. Later they added six feet to the wall, but for decades afterwards the opening in it was referred to in wonderment as the "Eliza Blue window."

Fifteen hours after she went on the lam, Eliza was picked up in a cornfield on the other side of Waupun. Her only other recorded transgression in captivity was "talking insolent to [a] matron" once, and on April 20, 1918, she was released.

Eleven years and four days later, Eliza Blue was back in front of a judge for being drunk and disorderly – and thrilled about it because now she wanted to escape into prison.

"I been for years tryin’ to get back amongst my friends," she told Judge George Page. "I wants to go back to Waupun, where I got me a lot of pals. That Mister George Benson, deputy warden, was the nicest man ever I see!"

Benson, as it happened, was now on the staff of the Milwaukee House of Correction. Eliza was delighted for the opportunity to renew acquaintances with him for 10 days, and couldn’t get there fast enough.