For the 10th straight year, October is Dining Month on OnMilwaukee, presented by the restaurants of Potawatomi Hotel & Casino. All month, we're stuffed with restaurant reviews, dining guides, delectable features, chef profiles and unique articles on everything food, as well as voting for your "Best of Dining 2016."

For over 125 years, there has always been a gathering place at the corner of Plankinton and Wisconsin. If the four walls of today’s Empire Building (710 N. Plankinton Ave.) could talk, they would tell colorful stories of nightlife empires rising and falling, formidable fortunes made and lost, and the brave and foolish gamblers who made history happen.

Known for swank sophistication as well as sordid scandal, the first floor Empire Lounge (716 N. Plankinton Ave.) was a gamble from start to finish. Today’s Mo’s Steakhouse occupies a space that traces its nightlife ancestry across multiple Milwaukee nightlife families.

Rise of the Empire

Henry Wehr’s saloon, later the Empire Hotel and Café, was one of the first permanent buildings to ever sit at the intersection of Plankinton and Wisconsin. The first Empire Block, a three-story Teutonic building, rose up around the saloon in 1898. The Browning Building, as it was later known, was one of the first homes of the Wisconsin Humane Society and radio station WEMP (EMP for empire, naturally). The building was known for its iconic rooftop advertisements, including a "smoking chimney" for Camel cigarettes.

Entering the skyscraper era, the tired old Empire Block just couldn’t compete with its more modern neighbors. It was razed in 1927.

On April 29, 1928, the New Empire Building – including the 2,558 seat Riverside Theater – opened for business. Soaring 12 stories above the street, the New Empire included offices, doctors, dentists, shops and a cafeteria. Truly, the modern emporium seemed to have something for everyone – except, during Prohibition, a saloon.

Throughout these dry years, West Water Street was still overserved by John Morgenroth’s nearby saloon at 756 N. Plankinton. The historic four-story tavern, gymnasium and gambling parlor had been in business nearly 50 years, and it served as the Downtown headquarters for sportsmen, politicians and men about town.

Prohibition meant nothing to John Morgenroth and his customers. Morgenroth’s was a civic institution; the same detectives and police officers who occasionally raided the bar were often long-time customers on a first-name basis with its owner. Morgenroth once received a watch made of solid gold from his top customers, which included governors, mayors and the heads of Milwaukee’s wealthiest families. He took care of them, and they took care of him.

Morgenroth was well connected to everyone – including Spencer Tracy, who rented out his upstairs flat, and Jack Dempsey, who visited the bar during every Milwaukee match. At "Honest John’s," nobody went hungry. Huge platters of corned beef and cabbage were offered free to underfed guests. Gambling men of limited means weren’t allowed past the doorman, and any man whose wife complained about his gambling losses would see his money returned (and his future visits forbidden).

John Morgenroth retired in 1931 and died of diabetic complications in 1935. "The city has lost one of its most metropolitan and colorful figures," said the Milwaukee Journal. "He belonged to the age of big pot poker games, where the sky was the limit and a man might lose his actual shirt between midnight and breakfast."

When Morgenroth exited the business, Fred Jordan stepped in. Jordan, a former boxer and notorious gambler himself, reopened the bar as "Jordan’s Sportsman’s Headquarters" after Prohibition. The real business was the gambling operation. The "Manhattan Club," his illegal upstairs casino, was raided on Oct. 24, 1935 and 94 men were arrested. The raid happened during the dinner hour rush and tied up Downtown traffic for over an hour.

Busted several times more between 1935 and 1940, Jordan was on the verge of losing his building when he petitioned the Common Council for a new liquor license. The Empress burlesque house had already been razed for a parking station, and rumor had it the unseemly saloon would be next.

The rumor was nowhere near true. Morgenroth’s saloon later housed Baron’s Gay 90s (1952-1958) and the original location of Nino’s Steak Round-Up. Under Nino Costarella’s leadership, Nino’s would grow to a chain of over 30 restaurants in four states. After being progressively damaged by a series of kitchen fires, Nino’s vacated 756 N. Plankinton (where it boasted the first restaurant boat dock on the Milwaukee River) in 1970, and the building was razed for parking in 1972. The last Nino’s steakhouse in America closed in Sheboygan in 2011.

Nonetheless, Fred Jordan got his license and moved his business to 716 N. Plankinton Ave. Out went the Empire Hat & Shoe Co., and in came the Empire Bar. Let the good times roll!

From watering hole to wonderland

The original Empire Bar was just one long, narrow, dark tavern. Decked out in dark woods with hints of brass, the bar was a popular happy hour spot for employees of the Empire, Pabst, Caswell and Plankinton buildings. Although capacity couldn’t have exceeded 20 customers, the bar was consistently busy.

As the story goes, a young piano player from West Allis offered to help Fred Jordan get his business off the ground. He was already playing at the nearby Red Room Bar for $35/week, but was willing to cut the Empire Lounge a deal. Not willing to invest in a piano, Fred Jordan told the entertainer he was overpaid and sent him on his way. That entertainer would later command $50,000 a week, performing in Las Vegas under the name Liberace (to be fair, Jordan wasn’t the only one who passed over Liberace. Another Milwaukee supper club owner, so enraged by Liberace’s untapped success, got into a fight with his booking manager in 1955 that left one of the men dead).

Jordan had a hit on his hands, but as an Elm Grove resident, he didn’t have the city residency required of Milwaukee liquor license holders. While the Common Council debated whether or not to revoke his license, state beverage tax agents raided the bar in 1944 and found mismarked liquor bottles with diluted contents. The chief of police requested that the city shut down the Empire Bar. With two strikes against him, Jordan wasn’t betting on a third. In 1945, he put the business up for sale and moved on to new ventures, including Jordan’s (8801 N. Port Washington Rd.).

Following a sensational bankruptcy and divorce, Fred Jordan opened a bar and grill at 621 N. Broadway in 1959 following the demise of the Pink Glove, one of Milwaukee’s first known gay bars. He later opened Jordan’s Tavern at 219 E. Michigan (now the Swingin’ Door Exchange) where he was charged with gambling in 1967. In 1994, Fred Jordan died at age 95 in Wood, Wisconsin.

Enter Alex J. Korchunoff, the popular proprietor of Korchunoff’s Tavern (1341 W. Highland Ave.) and a former West Division football star. Alex and his wife Billie would grow the business to greater heights than anyone could have imagined. At the Empire Bar’s 10-year anniversary party, Alex announced an exciting – and ironic – new concept that reinvented the bar forever.

"The piano bar innovation is certainly catching fire in Milwaukee," reported the Milwaukee Journal. "It has progressed from the novelty stage to the point where its absence almost becomes conspicuous. Starting as a spark, the piano bar has since burst into flame – shedding its luminosity at The Crest, Holiday House, Tic-Toc, Scalers and Jimmy Fazio’s. Last night, we heard that Korchunoff’s Empire Lounge will be added to the list shortly."

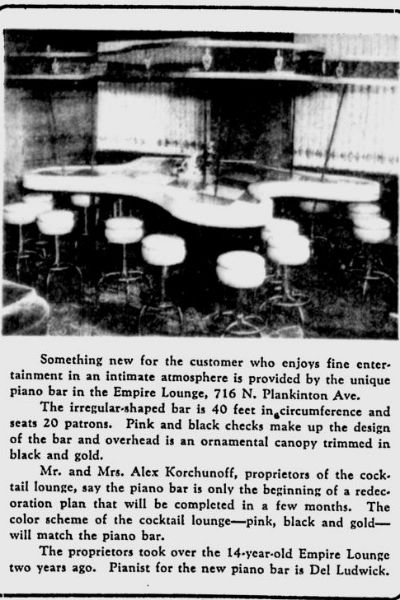

The Korchunoffs expanded into an adjoining retail space and doubled the size of their business. Both rooms were completely redecorated in pinks, blacks and golds. No longer just a bar, the renamed Empire Lounge promised "discriminating drinks" with "atmosphere supreme" and resident performers.

Cocktail waitresses were required to be single, over 21 and able to wear costumes. The Empire Lounge hired only the city’s best bartenders and only the nation’s best live entertainment. It became an exclusive, elegant and upscale nightlife destination throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Any untoward reputation inherited from Fred Jordan was quickly forgotten. Despite two unusual "raids" in 1961 (for a waitress in a full-body bunny costume) and 1962 (for lower lounge lighting than police preferred), the Empire Lounge had a sterling police record.

The Korchunoffs became the hero and heroine of Milwaukee’s high society. News reports of their social, charitable and business activities were published in local papers, along with photos of their family vacations. They were living the American Dream.

Changing times, changing hands

Although the Empire Lounge was growing, the Downtown office market was shrinking. The Empire Building was only half full, and long-deferred renovations were deferred even further by a "Downtown freeze" on new construction. While the Korchunoffs kept the Lounge in top-notch condition, the same could not be said about the eleven stories of outdated office furnishings above. In 1953, the Empire’s owners tried to sell it to the State of Wisconsin, who opted to build in the Civic Center area instead.

In 1956, the Empire Building (and nearby Banker’s Building at 208 E. Wisconsin) sold to the owners of the Empire State Building in New York City. A year later, the Empire was sold again to a Chicago developer who promised (and underdelivered) a half million dollars of improvements. When the building sold in 1961 to Joseph Zilber, president of Towne Realty, it was still half empty – and the new Marine Bank Plaza was causing tremendous competition in an aging Downtown. With occupancy down to 30 percent, Towne Realty invested significant dollars to bring the Empire back. Plankinton and Wisconsin was still considered the busiest intersection in Downtown Milwaukee, after all.

After running the Empire Lounge for over 25 years, Alex and Billie Korchunoff exited the nightlife business, their corporation and their marriage, which ended in divorce in 1972. Although Alex and Billie eventually married others and left Milwaukee, they both returned to Wisconsin in their senior years. Alex and Billie have both passed away, but their family members remain in Milwaukee to this day.

William Kling was named Empire Lounge owner/operator in 1972, although it’s believed that Alex Korchunoff remained a silent partner. Given the Korchunoffs’ hard work building a high-end reputation, it’s hard to imagine they were thrilled with the Sexual Revolution that followed their exit.

In October 1973, the bar was sold for $10,000 cash. Soon after, print ads appeared, announcing "Empire Lounge: It’s NEW!" How new it was. The Empire Lounge now offered an "intimate atmosphere for couples" sordidly lit in hot pink light bulbs – and exotic go-go dancers nightly after 7 p.m.!

"The venerable old piano still plays," commented a Milwaukee Sentinel reporter, "although it’s more likely to be adorned with a coquettish kitten these days than a respectable candelabra." Big name pianists’ names were replaced by the names of dancers: Bambi, Vixen, Cocoa, Candy and – good grief – Charlie Brown. Sex was selling – but it was selling too well.

Strip joints like the Downtowner, Brass Rail and Ad Lib had already brought adult entertainment to Westown. By the time the Empire Lounge joined this circuit, Downtown didn’t just have a thriving red light district: It had an open prostitution market powered by hundreds of weekend visitors from the Great Lakes Naval Base.

"The hookers are everywhere: along the sidewalks, mingling with the sailors as they walk along the street, standing in doorways and sitting in restaurants," said the Milwaukee Journal in October 1973. "Although nobody knows how many prostitutes are working Downtown on a typical weekend, estimates from police officers and Downtown businessmen range from 30-70 on the streets alone."

"Long before the first spit shined shoe hits Milwaukee streets, the bar managers are hustling squads of strippers and go-go dancers from bus to bus, shouting at sailors and promoting their businesses," reported the Journal in July 1974. "Hurry, hurry," hollered one manager as he ran along the curb "The Empire Lounge, boys, two drinks for the price of one at the Empire Lounge."

Sailors were frequently robbed, drugged and beaten up by hookers and their pimps. When they weren’t being lured into the Towne, Antlers, Wisconsin or Belmont Hotels, they were lured to faraway "trick pads" by single women in Downtown bars.

After six Downtown bars, including the Empire Lounge, were busted for prostitution in summer 1974, Ald. Kevin O’Connor implemented new penalties for bar owners. "We are cracking down on street solicitation," said O’Connor, "and we need to prevent business from moving indoors. We cannot let bars become havens for prostitutes."

At the height of the women’s liberation movement, Downtown bars reacted to the situation by banning single and unaccompanied women from the premises. Local women’s groups found the ban discriminatory and offensive as it all but accused any independent woman of being a prostitute. The controversial ban remained in effect at some Downtown venues into the 1980s.

Tougher times called for tougher leadership. In May 1975, Joseph Enea slyly acquired the Empire Lounge. Having worked at the Balistrieri family’s Ad Lib, Downtowner, Melody Room and Scene nightclubs, Enea was an expert in the highs and lows of the Milwaukee strip joint scene. Yet, oddly enough, he wasn’t interested in running the Empire Lounge as a strip joint. Jealous of the longterm success of Angelo Aiello’s Mint Bar (422 W. State St.), Enea saw an opportunity to make cold hard, uncomplicated cash by converting the Empire Lounge to a gay bar.

This was a strange move, considering the Empire Lounge had already been appearing in national gay guides for years. The GLIB Guide commented in 1973, "Different '40s décor, hosts straight early and becomes gay as night falls."

Due to Enea's police record and the Ad Lib’s tax burden, he was unable to get a bar license. According to FBI reports, Frank Balistrieri was unsympathetic: His stance was that Enea had gotten himself into trouble and would have to get himself out of trouble on his own. With a little help from his friends, including two license holders serving in name only, Enea launched his new Empire Lounge concept in summer 1975.

The switch was disastrous. Operating as an eccentric piano bar for over 20 years, the Empire wasn't ready or willing to embrace the disco beats of gay liberation. Enea lost not only the troublesome go-go crowd, but also the faithful older gentlemen who had been discretely visiting the Empire on the down low for decades. Enea underestimated how much Empire Lounge patrons valued style, sophistication and, most of all, privacy. Under legal and financial heat, and substantial tax liens, Enea closed both the Empire Lounge and the Ad Lib within six months.

Enea was later accused of criminal trespassing after selling off the Empire Lounge’s fixtures and furniture, including the iconic piano, in November 1975. Following a sudden stroke, he passed away at age 44 in March 1976.

By that time, the Empire had been bought, renamed "Airlines Empire Lounge" for reasons unknown and refocused on cocktail lounge chic. Roger Emerson, who had a hand in running The Beer Garden (3743 W. Vliet St.), is believed to have been involved in the resurrection. Gone was the ban on single women; ads beckoned to secretaries to enjoy classic cocktails in a cozy, comfortable afterhours environment.

However, it didn’t last. The space was vacated again in 1978, and the Empire Lounge name was permanently retired.

After the fall

Nightclub operator Sal Monreal, late of Club Monreal (1566 W. National Ave.), El Cid (1570 W. National Ave.) and The Bull Ring (1532 E. Belleview Pl.), took over the space with the San Francisco Pub from 1979 to 1982. The Baker Street Tavern later replaced it, but little is known about that property.

Piano music finally returned to the Empire Building in 1993, when the Clock Steak House moved into the expanded Empire Lounge space. After 50 years at 715 N. 5th St., the Clock had moved to 800 N. Plankinton Ave. in 1979 when its original home was razed for Time Insurance parking.

"Walking into the Clock Steak House was like walking into a Humphrey Bogart movie, complete with 1940s décor," said the Milwaukee Journal. Its pink historical placemats told tales of gamblers, sporting girls, underworld types and the well-to-do all gathering for schmaltz and butter-fried steaks. Owner Oscar Plotkin, once regarded as a "top man" in the Downtown gambling scene, managed the business until the day he died. According to legend, Liberace once played the Clock Steak House’s original location but was kicked out for being underage. Claude Dorsey stepped in as the Clock’s resident solo and singalong piano man and stayed for almost 40 years.

The Empire Building’s street level façade was refreshed, and the Clock Steak House absorbed a small retail storefront at the building’s north end. Unfortunately, after 68 years in business, the Clock Steak House quietly closed in 1997.

The short-lived Grille 720, owned by Royal Taxman, occupied the space from 1997 to 1999.

Echoes of the Empire

In June 1999, Johnny Vassallo opened Mo’s – A Place for Steaks at 720 N. Plankinton Ave. For 17 years, the award-winning restaurant has served up upscale ambience, atmosphere and spirit rarely found elsewhere in the city. With live piano music, sizzling steaks and classic cocktails, Mo’s has kept high-end hospitality alive and well on Plankinton Avenue, but at other Mo’s locations across the country. Of course, few visitors to this Downtown destination have any idea what came before – and as time goes on, even those who do remember will eventually forget.

Still, decades after the Empire Lounge’s closing, its echoes can be heard on Plankinton Avenue nightly. And it’s a six star experience that would make its Westown neighbors and forefathers – Henry Wehr, John Morgenroth, Fred Jordan, Nino Costarella, Oscar Plotkin, Alex Korchunoff and their successors – rather proud.