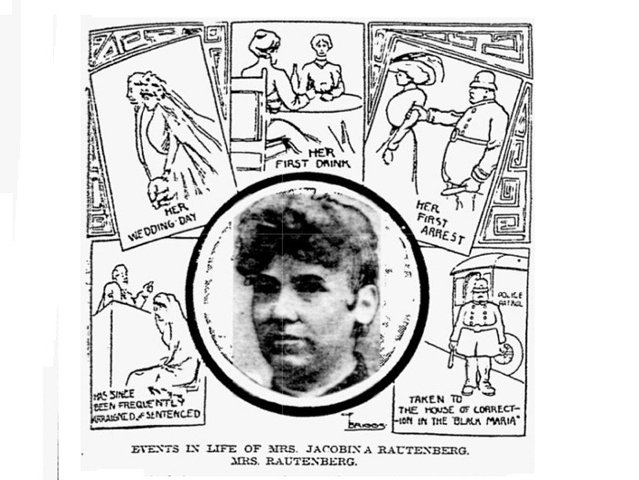

Jacobina Rautenberg's repeated arrests for public drunkenness from the late 1890s up to her death in 1935 made headlines, and as the newspapers kept score – "Add one for Jacobina," "Going up: Jacobina makes it 128," "Jacobina again refills, record mounts to 141" – that distinctive first name became as familiar in its own right around town as Pabst, Miller and Schlitz.

When the papers weren’t yukking it up about the old soak who spent so much time at the House of Correction the superintendent’s children considered her their aunty, they steeped her in sob-sisterly pathos.

"Groping her way through life, she finds no hand held out to her with succor," wrote Claude Chesley Manly in The Milwaukee Journal on Nov. 15, 1911. "If society had reached out a hand of pity and helped her to regain her footing after her first fall, if she had been put into the hands of competent physicians until her newly acquired craving for alcoholic stimulants had been overcome, if she had been reformed instead of punished – she might today be a worthy wife and mother and a respected member of society."

Jacobina herself was ambivalent about her drinking. She drank, she said in 1913, "to drown out my troubles." But she had been anything but morose at her 75th court appearance a few months earlier that year.

"Make it light, judge," she told the magistrate. "This is the diamond jubilee!"

A native of Germany, Barber moved to Milwaukee as a young girl with her parents. According to a 1928 story in the Journal, Jacobina’s English "was learned at the Third Ward school. Her father died young. Jacobina married a sailor of the Great Lakes. A ship’s accident crushed his leg and his sailing days were over. A daughter died from diphtheria."

Husband William Rautenberg became a door-to-door peddler of fruits and veggies.

"Then he met this woman – a married woman, too," said Jacobina in the article. She followed him one day and confronted the lovers.

William threatened to break her neck on the spot, and "there was never any peace after that … He used to beat me if I complained. I was jealous, of course, at first. Then I turned him away, but I always took him back."

In a newspaper story 17 years earlier, however, Jacobina had remembered her introduction to alcohol differently. She was at her home at 529 Orchard St. on an October day in 1899 when a female friend came calling with a quart of whiskey.

"…It was the first time in her life that Jacobina Rautenberg, mother and housewife, was drunk," recounted the story. "A discussion over some trivial matter began between the two drunken women and angry words and blows followed."

Jacobina went to jail for the first time.

The Rautenbergs had two grown sons, William Jr. and Frank. When the above article was printed in 1911, Jacobina and Frank were both serving sentences at the House of Correction for drunk and disorderly.

"During the past two years neither the mother nor son have been out of prison for more than 10 days at one time," said the Journal.

William Sr. had paid so many fines for his wife "that a mortgage rests upon his home."

Three months later, a Journal reporter interviewed Jacobina’s "hard working man" on the eve of her release.

"She has a key to the house," William said. "I don’t know whether she will come home or not. I am satisfied that it will be the same old story. I’m getting too old now to keep track of how things go with her. She lost interest in herself years ago. However, I will not turn her out."

"If (William) would be kind to me I wouldn’t drink a drop," Jacobina said in 1913 at the House of Correction. "My hand I give you on it."

Eventually William passed out of the picture and Jacobina found a new scapegoat.

"Women are to blame," she said in 1928. "That woman (her husband’s girlfriend) was. What did she want to tempt a married man for? The girls today are to blame. What for do they want to go riding with fellows they have never seen before? You can’t tell me they’re not to blame."

She had just gotten out of jail again and was living with Frank at 614 Second Ave. It was a tender homecoming.

"It’s too damned bad they didn’t keep you out there for 30 days," growled her son.

When Prohibition went into effect in 1920, Jacobina reportedly went on the wagon for a whole year. After she fell off, she imbibed whatever was available at speakeasies or from moonshiners whose product she derided as "fusel oil" but drank anyway.

Riding the streetcar she tried to be cagey, hiding her hooch in a basket, covering it with newspapers and putting a prayerbook on top of the papers. She’d end up asleep in some doorway or singing, dancing and directing traffic on a busy street.

In 1926, Jacobina took the pledge. "Never again!" she told a Milwaukee Sentinel reporter at the House of Correction. "I’m never going to drink anymore!"

But her resolve didn’t even last for the length of the interview. "Except maybe for a little nip of wine," Jacobina amended.

"It is not because I care for the drink," she once said. "It is to drown out my troubles … When there is unhappiness and great trouble, then it is the drink that helps … Just a little and then a little more, and ach – there is no more trouble. You forget it ever was and you grow so happy and so comfortable and so glad."

She was playing traffic cop when hauled in for the 129th time on June 21, 1928. It was a milestone reported throughout the country because it broke the Milwaukee record for arrests long held by Ned Hogan, an earlier famous tippler.

"Boosters of the idea of the true superiority of the weaker sex point out that Jacobina has seldom if every been arrested for anything but being drunk," noted The Journal, "whereas Mr. Hogan, previous record holder, frequently had to throw a brick through a window in order to get out to the House of Correction."

The Associated Press crowned her "the world’s most arrested woman" when Jacobina was booked for the 140th time on Aug. 9, 1929. Judge A.J. Hedding told her he would suspend her sentence on her promise not to get arrested again for at least a month. Jacobina agreed.

Five days later she was back in Hedding’s court after getting pinched at a rowdy party at a friend’s house. "It’s not my fault," Jacobina told the judge. Her friend had "made" her get drunk.

A year later, Milwaukee Sentinel reporter Dixie Tighe got an investigative assignment from the City Desk. "Jacobina Rautenberg has not been arrested for a long, long time. Go see what’s the matter."

Tighe found her in the county infirmary, crippled by rheumatism. Jacobina was almost 74, but with her smooth skin and bright eyes, wrote Tighe, looked 60. Anticipating a "cranky, surly woman who would probably be hardboiled about the interview," instead Tighe found a sweet old gal who "loves to laugh, and there are still many things that amuse despite the fact she has had a long life of unhappiness and hardships of mind, heart and body."

"If I had been happily married I should never have found trouble through drink," Jacobina said. "I was married when I was not quite 16. My husband loved me oh-so-much then; he was jealous, attentive, kind. But he drank too much. He struck me cruelly. I should have left him then, I know. But there were my children – I wanted to make things go."

She had advice for young women: "Have a good time – observe, get magic glasses and look straight through men."

"Who knows," she said with a twinkly smile as Tighe departed, "maybe I’ll marry a nice old soldier and be happy."

Jacobina died alone at 81 on July 24, 1935.

The headlines on her obituaries in the city’s two major dailies illustrated the media’s confliction regarding Milwaukee’s most besotted citizen.

"Jacobina loses troubles for good as death comes," said the Journal.

"Drinkingest Old Lady," headlined the Sentinel.