"Bar Month" at OnMilwaukee is back! For the entire month of March, we're serving up fun articles on bars, clubs and beverages – including guides, the latest trends, bar reviews, the results of our Best of Bars poll and more. Follow along with the #DrinkOnMke hashtag too. Grab a designated driver and dive in!

LOUISVILLE, Kentucky – You could call it the house that bourbon built.

But it might be more accurate to describe the Fort Nelson distillery, 801 W. Main St. in Louisville, as the house that Michter’s re-built.

When the owners of the revived brand – which had its roots in Pennsylvania – announced that they’d open a distillery on Main Street in 2011, it was a pioneering move. No one else was distilling downtown at that point.

But by the time the facility finally opened to the public in February 2019, the landscape had changed dramatically and now there are at least eight other stills in operation nearby.

How did that happen?

"We were the first ones in modern times to announce a downtown distillery," says co-owner Joseph Magliocco. "We had a wonderful announcement in front of the building.

"Then two weeks later I got a terrifying email that there was imminent danger, a catastrophic failure of the building. It was not good."

Thanks to decades of vacancy and neglect, and the removal of interior floors that had been contributing to stability, the long wall running along 8th Street had bowed out 23 inches at the roof.

"At that point we hadn't closed (on the sale)," Magliocco recalls. "I don't remember the exact contract, but I think we had a pretty good reason for saying, 'hey, you know, this due diligence discovered something that's quite expensive and quite terrifying'."

Michter’s, he means, could have walked away.

But it didn’t.

Instead, it spent an unexpectedly large barrel full of money – nearly $8 million – and eight years renovating a dilapidated building into its gorgeous new Whiskey Row home.

Why?

"I really like architecture, I studied it a bit when I was in college and I loved it," says Magliocco. "I still love architecture, and it just seemed like a wonderful old building. It's also a great location, right opposite the Louisville Slugger Bat Factory museum, which gets over 300,000 visitors a year. We're down the block from the Frazier History Museum (the official Kentucky Bourbon Trail welcome center), which is great. So it seemed like just an amazing building in a wonderful location.

"Fortunately, my partners were willing to do what we needed to do to save the building."

The Fort Nelson Building

The roots of the building – located in the West Main Street Historic District, which is on the National Register of Historic Places – are a little cloudy, though we know it’s long been called the Fort Nelson building because it sits on the site of the second on-shore fort along the banks of the Ohio River in Louisville. (Fort-On-Shore downriver was the first.)

The one-acre fortification was completed in 1781 by troops under George Rogers Clark, who served as the Kentucky militia leader for much of the Revolutionary War. It sat between Main Street and the river and 7th and 8th Streets. The site of its main gate is now occupied by Fort Nelson pocket park.

The current building on the site was completed in 1890 and is erected of brick and stone with cast iron elements, in an area renowned for its collection of cast iron facades.

The architect is unknown, and even the completion date seems uncertain, as different sources refer to it as dating to the 1870s, 1880s, 1890s and, most specifically 1890.

Numerous sources say that the building survived the famous Louisville Cyclone tornado of 1890, which sheared the top floors off an adjacent building. It also survived the two great floods of 1913 and 1937.

Whoever designed the place – which stands tall, lit like a beacon at night – created a beauty.

The four-story building has beautiful Romanesque arches and a regal peaked, overhanging corner turret made of cast iron and stone on the top floor. Along the 8th Street side, constructed of red brick, there are bays of arched windows capped with stone hoods.

The cast iron and stone facade is adorned with capitols and my favorite feature is the fenestration on the front. Two large arched windows on the second floor support three smaller ones on the third floor, which, in turn, hold up the four even smaller ones on the top floor.

If you’re inside the building, you immediately know which floor you’re on just by looking toward the front windows.

On the exterior west wall is a ghost sign advertising the Fort Nelson building and one of its previous tenants, which, over the years, have included Hetterman Brothers Cigar Manufacturers (1893-95), J. Zinsmeister & Brother Wholesale Grocers and Coffee (1897-1910), Bouvier Specialty Photo Manufacturing Co. (1911-14), Mahan Products coffee roasting (until 1929), Maury-Cole Coffee Roasters (1929-35), Ben Snyder Department store, which used it as a warehouse (1942-74) and River City Airplane Works (1982).

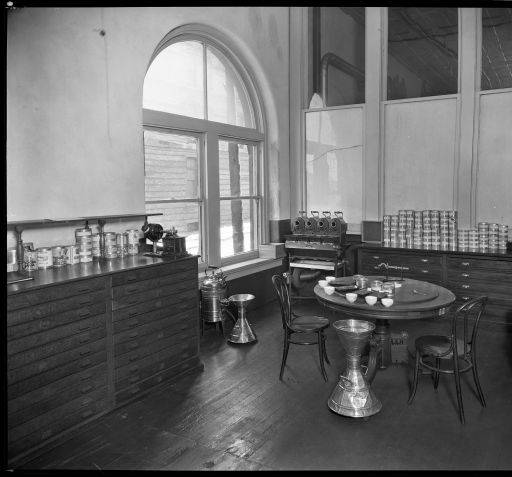

The Mahan's coffee cupping room. (PHOTO: University of Louisville archives)

A coffee company brewed up plans for a java museum in the building, which it later donated to the city. The museum never materialized.

In 2009, then-owner Paul Bariteau and two others were severely injured when a staircase collapsed inside and sent them plummeting about 30 feet.

Perhaps the most intriguing occupant, considering the current owners, was N. M. Uri Wholesale Whiskies.

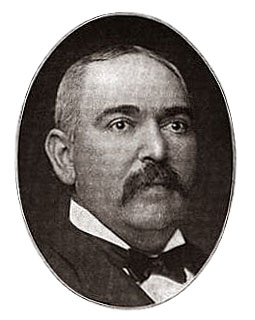

The son of German immigrants, Nathan Uri’s sister Amanda married Isaac W. Bernheim, who is is legendary in the bourbon industry. Uri (pictured at right), joined Bernheim Brothers’ whiskey business in 1875, but struck out on his own in 1891.

After launching a wholesale business, Uri bought the former Gwynn Springs distillery four miles north of Bardstown, in Nelson County, in 1903 and renamed it International Distillery.

Uri’s wholesale business was in the Fort Nelson building from 1916 until 1919, closing – as did his distillery – when Prohibition arrived, though a walled up doorway in the basement has led some to speculate that the building’s connection to whiskey didn’t end with the dawn of a bone-dry America.

Did this doorway lead to a Prohibition-era tunnel? Some say yes. (PHOTO: Michter's)

Michter’s

Michter’s has a history that pre-dates even the construction of the original Fort Nelson.

Founded in 1753 by Swiss Mennonite farmer brothers Johann and Michael Shenk, the distillery near Schaefferstown, in eastern Pennsylvania, is said to have received a visit in 1778 from General George Washington who purchased whiskey to warm his troops during the long winter at Valley Forge, about 50 miles to the southeast.

Upon Johann’s death in 1827, the distillery became the property of his son-in-law John Kratzer, who sold it a year before his death to another family member, Abraham Bomberger, in 1861.

Bomberger’s wife was Johann’s great-granddaughter, Elizabeth Shenk Kratzer.

When the distillery was shuttered by Prohibition, it had been owned by the same family for 167 years.

According to BourbonScout.com, Bomberger’s reopened after Repeal and it was then sold a number of times, and was, for a time, called Penndale, before it was sold to Louis Forman in 1942.

After Forman’s short-lived ownership of the distillery, it became Kirk’s Pure Rye Distillery and then Pennco, when it was again purchased by Forman, who renamed it Michter’s, a combination of the names of his sons Michael and Peter.

Michter’s declared bankruptcy in 1989 and county officials took over the property, which was falling victim to the elements and vandals.

In 1997, New York liquor importer and producer Chatham Imports' president Joseph Magliocco partnered with Dick Newman to buy the brand.

Sourcing whiskey from the likes of Heaven Hill and Barton, Michter’s became sought-after, leading Magliocco to plan a new distillery on Main Street in Louisville – which has the Butchertown-made Vendome copper still and the wooden fermentation vats from the Pennsylvania distillery – and a bigger distillery in the suburb of Shively.

Distilling at Fort Nelson

On July 6, 2011, hopes ran high as the mayor and governor joined Magliocco at 8th and Main Streets to announce the return of distilling to downtown Louisville.

"Michter’s new distillery not only creates jobs for Louisville, it brings a significant bourbon presence to downtown while also saving a historic treasure in the Fort Nelson building," said Mayor Greg Fischer that day.

Then, on July 22, the letter arrived from engineering firm Structural Services Inc.

"Since the building construction is non-reinforced masonry, a sudden catastrophic collapse is possible. A sudden building failure could be initiated by progressive lateral movements, a wind event or a seismic event. A building failure would affect the building directly adjacent to the west and the public spaces to the north east and south."

The City of Louisville immediately instituted lane closures on 8th Street in case of collapse.

Michter’s pushed forward, closed on the building in 2012 and hired Louisville architects Joseph and Joseph, which has experience working on distilleries, to spearhead the project.

"The solution was to build essentially a steel cage structure inside the building and then tie the brick to the steel," says Magliocco.

"That was the only way to save it. Otherwise we could have kept the facade and ripped down the building. It would've been probably a lot faster and a lot cheaper, but obviously, we don't think that would have been as good a result.

"It was a complicated project in that you're working on this beautiful 1890s building and you're working in a downtown environment and you're trying to shoehorn a working distillery into it. There were a whole bunch of different challenges."

Some of those challenges are right there for the naked eye to see when you visit Michter’s today. The 400,000-pound steel cage is plainly visible inside the building, the first floor of which houses the distillery, shop and tasting room in a multi-story space, and a bar at the top.

Outside on the 8th Street side, you can see a series of star-shaped elements. Those are where the cage is bolted to the exterior structure.

Back inside, you can see a severe vertical crack toward the rear that has been laced back together via a series of steel straps.

The result is that the building is surely as strong as, if not stronger than, ever.

When I visited, our personable and knowledgeable tour guide Jordan Hamilton was reassuring.

"It is a very safe building. Our contractors and architects have all said in the event of an earthquake, this is exactly where they want to be. A: because of the safety of the building. B: in my opinion, probably because all the whiskey we keep in here. It would be a good place to hole up for a while if you had to. I don't foresee that happening today, but if it does, we're in safe hands here in this building."

No one seemed worried. The tours were booked solid the November weekend I visited Louisville, the shop was doing brisk business and there was nary a seat to be had upstairs at the bar.

The space is airy and bright, with a modern vibe, but with exposed brick to remind us of its vintage. And if you look closely, you can see where there was once an interior staircase – perhaps the one that collapsed – reminding us of that low point of the Fort Nelson building’s history.

Less than a year after Michter’s long-overdue grand opening date, Joseph Magliocco sounds like an eternal optimist.

"We're very fortunate," he says. "A lot of the other distillers have done great work downtown. Other people have done great work downtown, too. It's created a critical mass ... I think that the different distilleries that people can now visit here actually create a critical mass that helps everybody."

With the highly acclaimed Peerless barely a five-minute walk away and the Evan Williams Bourbon Experience just across the street, there is definitely a hot spot of three highly celebrated whiskeys right there in a very short stretch of West Main Street.

"Michter's is not a huge brand but whether we're doing it or not, the goal was to make the greatest American whiskey," says Magliocco, brushing aside countless accolades for his whiskey.

"We have a lot of really good people working really hard to try to produce really good stuff. And the building just seemed like a little jewel. It just seemed to really fit well with the brand and the history of what we're trying to do."

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has be heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.