For more on "Making a Murderer" and other potential suspects, click here.

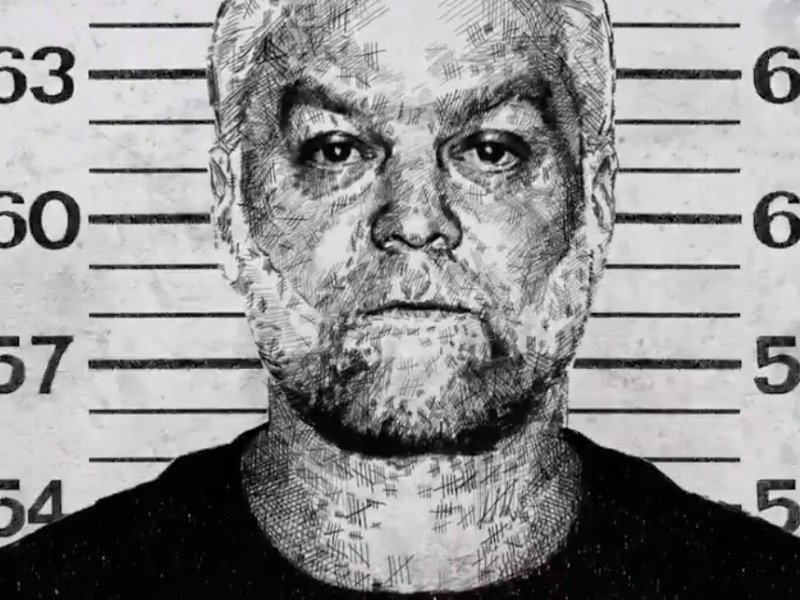

Did Steven Avery murder photographer Teresa Halbach? I’m not sure anymore. He might have. Some in Manitowoc County law enforcement have a lot to answer for, though.

Furthermore, Avery’s very cognitively slow, mumbling and malleable nephew Brendan Dassey, who was only 16 when Halbach died, probably deserves a new trial. Dassey’s conviction – he is not eligible for parole until 2048 – strikes me as potentially being the greatest miscarriage of justice here, coming as it did without any grounding in forensic evidence against Dassey.

It should strike fear in anyone who truly understands the awesome power of government, especially when wielded against a cognitively challenged special education student who was lacking money, intellect and social capital.

I'm realizing these things after binge-watching Netflix’s 10-episode true-crime documentary "Making a Murderer" over the weekend.

The documentary series, which is garnering rave reviews and escalating social media buzz, depicts Wisconsin as a snowdrift-covered backwater filled with kohlrabi-growing rubes, junk yards, cigarette-smoking weathered-faced frizzy-permed people who could use a trip to the dentist and colorless – possibly corrupt – cops who wear ill-fitting suit jackets that look like they came out of the wardrobe chest of a 1970s-era TV police series.

Officials are already blasting back hard, claiming the documentary is unfair and slanted toward the defense. They’re right about the last part. It’s definitely slanted toward the defense.

Also: Do we really have accents like that? Well, I grew up in northwestern Wisconsin, so I know we kind of do. The series reminded me of the Coen brothers’ movie "Fargo," with a burn pit instead of a wood chipper and, sadly, a very real victim: Halbach, who died at 25.

Before watching the series, I was certain that Avery was guilty. Dassey too. Both disgusted me, actually. I am not a person who usually buys into the "cops framed me" type of defense. If you are from Wisconsin, as I am, you probably remember Avery. He was the Manitowoc County man with the flowing blonde beard who served 18 years in prison for a sexual assault that DNA later proved he did not commit.

The Wisconsin Innocence Project helped free him and, for a time, he became a cause celebre to Wisconsin politicians, Democrats and Republicans alike. It was weird to watch a parade of politicians from Wisconsin’s past on Netflix, from Peg Lautenschlager to Jim Doyle. I also saw a bunch of lawyers and reporters I’ve met and landscapes I’ve driven.

Not long after Avery’s release, with his civil suit against Manitowoc County law enforcement heating up, Avery was charged in the murder of Halbach, who was at his family auto salvage yard to photograph a van and whose bone fragments were found in a burn pit next to his trailer. He is serving life in prison without the possibility of parole.

The series did what I didn’t expect, though: It slowly changed my perceptions about the cases. By the time the final episode had finished, I was convinced that Dassey’s conviction is deeply flawed (his attorneys still have a pending appeal in federal court on his behalf). I am not saying Dassey didn’t do it. I don’t know who killed Teresa Halbach. I am saying everyone deserves fair representation.

I am less sure regarding Avery’s complicity. Maybe he did do it. There are things pointing in his direction, clearly. Is that reasonable doubt? Maybe. There are serious questions remaining, such as:

How the heck was it possible that Manitowoc County had publicly turned over the Halbach murder investigation to another county – due to Avery’s heating up and pending civil suit against Manitowoc County – yet it was a Manitowoc law enforcement officer who found a central piece of evidence inside Avery’s trailer (Halbach’s car key, with his DNA on it), after no one else saw this key during repeated earlier searches over the course of eight days?

This was an officer who had just been deposed in Avery’s highly contentious civil suit against Manitowoc County, which was why the Manitowoc County’s Sheriff’s Department supposedly backed out of the investigation in the first place. The depositions had occurred just days before the murder. Pretty odd, even though cops from another county were supposed to be watching.

And how was it that a Manitowoc detective found another key piece of evidence in Avery’s garage that everyone else had also missed – a bullet with Halbach’s DNA on it– and only found it months later, after searching by four other officers earlier had failed to find it? Pretty odd indeed.

Why did another Manitowoc officer who had just been deposed call in Halbach’s license plate to dispatch the day she was reported missing but before her car was found on the Avery property?

Why did the state crime lab analyst who accidentally contaminated a key DNA sample ask for a waiver to get around protocols that said contaminated samples should be ruled inconclusive and retested? (There was not enough of the sample left for retesting). This same analyst provided key hair sample evidence against Avery in his earlier sexual assault case, the sexual assault it turned out that he didn’t do. Weird, eh?

Frankly, if questions remain, that’s at least somewhat the fault of Manitowoc officers, who should have known better, simply stayed away and let others handle it. Now, there’s this odd overlay of characters turning up both in the past shameful wrongful conviction case of Avery and in this case too – and finding key evidence, no less, that others somehow missed. They could have avoided it. They should have.

There were essentially three key pieces of forensic evidence in Avery’s case: Halbach’s car key found in his house, the bullet in the garage and the blood of Avery and Halbach found in her car. There were other things that pointed to Avery, of course, in addition to Halbach’s bones in his burn pit. She was seen on his property, although numerous others lived on the property too, including other adult males. And her van was found in the salvage yard.

How was it, though, that there was literally no Halbach blood evidence found in Avery’s garage or home if Halbach was brutally murdered there? Not a speck. Why did the key not have Halbach’s own DNA on it?

Why did some of what might have been Halbach’s bones turn up miles away from the Avery property?

Why weren’t others who lived on the property or who knew Halbach more thoroughly investigated?

Why was there a small hole pierced in the top of a vial of Avery’s blood from the earlier sexual assault kit, and why had the seal on it been broken? The defense claimed this blood was planted in Halbach’s car; prosecutors presented controversial and rare FBI testing to counter that.

Why would Avery commit a murder – especially of someone who would be instantly traced to him – when his life had taken a turn for the better, and he was poised to likely become a multi-millionaire? If he did do it, why would he leave evidence (the key, her car on his property) lying around, especially when he had a car crusher on the property and had been through the nightmare of a false conviction? Is that something someone who knows he’s a target does? Halbach was not reported missing until three days after she was seen photographing the van.

If your instinct is to say this is all ridiculous, that Avery and Dassey did it, without watching the series, you should watch it first. See if your opinion changes by the end of episode 10. Mine did. I get that it’s constructed entertainment-style reality told through the defense advocacy perspective (this is unusual in our true-crime fixated media where, whether it’s Scott Peterson or Officer Darren Wilson, the accused is generally painted as guilty, even before trial, because the media imply it’s so). However, the earlier media accounts – which is how most of us gained our understanding of the trials – were also constructed reality, in a sense.

Normally, I am not a fan of such "trials by media" in which the rules of evidence go out the window, and both sides don’t get a fair shake or equal time. That’s why I think, in Dassey’s case, a new trial in another courtroom should be in order. I admit that I haven’t read every shred of evidence in the cases, nor did I sit through either trial. I’m not a juror; I’m just a pundit with a keyboard.

However, the documentary is painstakingly built upon a literal and shockingly impressive mountain of video, audio and paper record evidence, collected over 10 years by two documentarians who started filming before the Halbach trial and actually moved to Manitowoc for years, turning viewers into eavesdroppers of real-time intimate family and attorney conversations.

This is not the reconstructed documentaries we usually see; it’s riveting stuff, filled with nuanced human characters, such as Avery’s overalls-wearing, common-sense talking, salvage yard owning elderly dad and his endlessly devoted mom. In some ways, it’s a parable about class and how devastatingly difficult it is for the poor and outcasts of society to go against the power of the state. You have to be rich or a celebrity to have a fighting chance.

I admit that my impressions of the case before the documentary derived from casual exposure to Wisconsin news coverage – mostly two things.

I remember then Calumet County DA (and special prosecutor) Ken Kratz – yes, the same DA who later resigned in a sexting scandal – reading the extraordinarily long, graphic and disturbing criminal complaint live in a press conference. I heard it on the radio. It was impossible not to have an emotional reaction of utter visceral disgust upon hearing the horrifying details. I remembered that this complaint seemed largely based on a "confession" by Dassey, Avery’s 16-year-old nephew. Pretty persuasive stuff. I went back and reread the complaint after watching the Netflix series and, untethered from the video and audio accounts, it remains grim stuff that enrages you into thinking Avery and Dassey did it.

But that only raises more questions.

Why didn’t then DA Kratz call Dassey to the witness stand to testify against Avery? You read that right. That big confession? He didn’t use it against Avery.

Why wasn’t there blood in the house if Dassey’s account was true that she was murdered in Avery’s bed? Were jurors really able to get the prejudicial pretrial publicity out of their minds? If Kratz didn’t think Dassey’s confession(s) were strong enough to introduce in his case in chief, why did he think they were strong enough to send Dassey to prison on? Kratz is now a private attorney in Superior.

However, I thought the most troubling passages of video dealt – bizarrely – with Dassey’s own defense team. Why did Dassey’s earlier defense attorney seem so determined to get him to enter a guilty plea when Dassey repeatedly said he didn’t do it? Why did his defense team private investigator cry on the stand when shown a photo relating to Halbach? Why did he appear to badger Dassey into changing his written statement – which originally said Dassey didn’t do it, in great detail – and to instead write one admitting guilt, including with diagrams the PI seemed to somewhat direct?

Why was it OK for law enforcement investigators to interrogate a 16-year-old with extreme cognitive slowness without a parent or lawyer? Why did his lawyer allow this? You read that right. Dassey’s lawyer allowed the cops to interview him without a lawyer present. How is that being a good lawyer?

Why did the defense team’s private investigator send an email to Dassey’s lawyer that trashed the Avery family as being a bunch of criminals? According to the Appleton Post-Crescent, "In the e-mail … sent May 9, 2006, to (the lawyer), he (the private investigator for the defense) wrote about the Dassey family, ‘This is truly where the devil resides in comfort.’ (The PI) also wrote that a friend of his suggested, ‘This is a one-branch family tree. Cut this tree down. We need to end the gene pool here.’"

What?!

These were the people working for Dassey, mind you.

Why did the jury not hear other parts of Dassey’s comments, in which he said things were put in his head? Or more expert testimony about the fallibility of confessions, especially of juveniles, and especially when not backed up with forensics? Why did Dassey’s later lawyer tell the jury that Dassey may have observed Halbach’s body in the burn pit, when Dassey had repeatedly denied this point to his own lawyers? It is all kind of creepy. Dassey’s excessively grinning first lawyer is pretty hard to get out of your mind.

You have to watch and listen to the many videotapes and audio segments of Dassey "confessing" and then "unconfessing" – you have to hear his slow-moving mannerisms and see his fogged over eyes and dim demeanor – in contrast to the skilled, intelligent, adult investigators, to really understand the problem here. At one point, he thinks he gets to go back to school after confessing to murder. Watch it. It’s hard to put into words. You have to hear him. Then watch him cave into his own defense team’s insistence that he put down evidence of guilt in writing and drawing as he repeatedly insists he’s innocent.

I am not prepared to say for sure that the uncle and nephew didn’t do it, though, particularly when it comes to Avery. If Avery didn’t do it, who did? Why didn’t Avery testify? (Yeah, I know that’s his right). If someone planted the bones in his burn pit, how did they manage to do this undetected? Ditto with the car. If someone else killed her, how did her car end up back on his property? Why was Dassey’s confession so detailed?

How would this work exactly for the cops to plant Avery’s blood in Halbach’s car? Again, they vociferously deny this. Were they really that determined to avenge a civil suit that would have held the county, not them, personally liable? Isn’t it often said that, when it comes to crimes, the simplest answer is usually the right one? Could it be possible that they planted evidence to make a case stronger against a man who was really guilty?

It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to see why Avery would be suspected – he was the last guy to see her alive, that we know of, and her bones were found in his backyard. I can understand how the jury got there. On the other hand, it’s not like he wasn’t convicted wrongfully before. He was, and some of the same people contributed to that. All very weird.

I am reminded of something one of Avery’s excellent defense attorneys said near the tail end of the series. He said that he almost hopes Avery did do it, because if he didn’t, the idea of this man who was once wrongfully convicted being set up again is nightmarish and horrific. Avery maintains he’s innocent. He’s literally back full circle, in prison, trying to prove it against great odds.

Of course, Halbach will never get to live past 25. I can’t imagine the pain her family has gone through, and now to see it dredged back up. They didn’t participate in the documentary, although her brother’s press conferences are prominently featured in it.

Absent new science, Avery’s best hope is to prove who really did it, if he didn’t, I suppose. That was woefully lacking in the series: Who are the other suspects? There were numerous other adult men living on the property, not just Avery, but the defense was barred from raising other possible suspects in court. Maybe Netflix worried about liability. Who else had the opportunity? The ability? The motive?

"Making a Murderer" raises lots of questions, but those two may be the biggest: If Avery didn’t do it – and that’s just an if – who killed Teresa Halbach? And why?

Jessica McBride spent a decade as an investigative, crime, and general assignment reporter for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel and is a former City Hall reporter/current columnist for the Waukesha Freeman.

She is the recipient of national and state journalism awards in topics that include short feature writing, investigative journalism, spot news reporting, magazine writing, blogging, web journalism, column writing, and background/interpretive reporting. McBride, a senior journalism lecturer at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, has taught journalism courses since 2000.

Her journalistic and opinion work has also appeared in broadcast, newspaper, magazine, and online formats, including Patch.com, Milwaukee Magazine, Wisconsin Public Radio, El Conquistador Latino newspaper, Investigation Discovery Channel, History Channel, WMCS 1290 AM, WTMJ 620 AM, and Wispolitics.com. She is the recipient of the 2008 UWM Alumni Foundation teaching excellence award for academic staff for her work in media diversity and innovative media formats and is the co-founder of Media Milwaukee.com, the UWM journalism department's award-winning online news site. McBride comes from a long-time Milwaukee journalism family. Her grandparents, Raymond and Marian McBride, were reporters for the Milwaukee Journal and Milwaukee Sentinel.

Her opinions reflect her own not the institution where she works.