MANITOWOC – To try and understand what all of this has been like, take a trip to Manitowoc County.

About an hour and a half north of Milwaukee but still 30 minutes shy of Green Bay, on a flat and flavorless stretch of Interstate 43 where – on this January day – the drab, white-and-brown landscape of snowy farmland is touched up only by red barns and blue flashing police lights going the opposite way, past the adult book store and the anti-abortion billboard in seeming juxtaposition, past the fireworks shop and the Kellnersville sign with no options listed under gas and attractions, and just south of the county line, there’s an exit for State Highway 147 toward Maribel/Mishicot.

Take it.

About five miles east of I-43, on an unremarkable and until-recently uncongested stretch of WI-147, past the archery range at Maribel Sportsman’s Club and the leafless trees of the Richard J. Drum Memorial Forest, over the bridge spanning partially frozen West Twin River but not as far as that of East Twin River and between two Christmas tree farms, with black smoke billowing from some bonfire too distant to send a smell and only the sounds of tires on asphalt and the whoosh of passing cars, there’s an intersection with a wooden post and two chillingly non-ironic signs bolted to it: Avery Road, Dead End.

Take it.

About 400 yards down the road, past the black-and-yellow "Avery’s Auto Salvage" billboard, adjacent to a great gravel quarry with its menacing DANGER warning that reads "Active Pit: Keep Out!" and onto an unpaved path behind a row of dense pine trees that, unlike their counterparts naked in winter, hide everything beyond them, there’s a green trailer with peeling paint and, parked in front, Dolores Avery’s Hyundai Elantra with its handicapped permit and a candy cane hanging from the rearview mirror.

A meeting here was mutually agreed upon 64 hours prior, but now there’s no answer at the door after numerous knocks. The Avery’s Auto office is closed, and two dogs – one tiny mongrel inside the home and a squat basset hound outside – are barking hostilely, knowingly, because this isn’t the first time they’ve encountered an interloper. And then, suddenly, there’s a red sedan speeding down the driveway straight at the visitor, drawing alongside at the very last second, spitting out an angry Charles Avery shouting through his cigarette that, "We ain’t doing no interviews!" and offering a very severe suggestion to get the hell off the property.

Definitely take it.

Back at the entrance to Avery Road, there’s a minivan pulled over with a cell phone pointed out the window snapping pictures of the signs. In front of the infamous "Avery's Auto Salvage" display, there are dozens of footprints in the snow, where locals grumble that looky-loos take smiling selfies to post on Facebook. And just a quarter-mile down the highway, an out-of-place Prius pulls a U-turn on two-lane 147, narrowly avoiding getting stuck in the icy ditch to double back and check out the notorious property belonging to the junkyard family that for so long wanted to leave the world alone – but now can’t get the world to let it be.

It is here, amid the farmland and the fields and the forest and the fires, in this barely corporated, backcountry no-man’s-land – the remote reaches of the 21st-most-populous county in Wisconsin – where humble is the default persona and everybody knows everybody, that internet curiosity has found its epicenter. It is here that a grisly tragedy a decade ago recently spawned a sensationally engrossing documentary that’s become an instant phenomenon and, in the process, made Manitowoc the current capital of popular culture.

A few miles east of the property on WI-147, which becomes Main Street in Mishicot (population: 1,442), regulars at a local bar disdain the lurid limelight cast on their hometown. In nearby Two Rivers, they say the unwanted attention will get worse before it gets better. And in the city of Manitowoc, the county seat with that courthouse and that sheriff’s department, nearly 14 rural miles south of the Averys, they’re already sick and tired of this whole thing.

While true-crime fanatics obsess over every possible theory, piece of evidence and alternative suspect, and a nation of Netflix-viewers calls for pardons, new trials, punishment for law enforcement (including, disturbingly, death threats to sheriffs) and a revamping of the entire U.S. justice system, the people in the place where everything actually happened are simply not interested.

Manitowoc County residents, caught in a murder-made media maelstrom they never asked for and are not benefiting from, just wish it would all go away.

The case, the documentary and now the fallout. This is the story about the story about the story.

A county fatigued

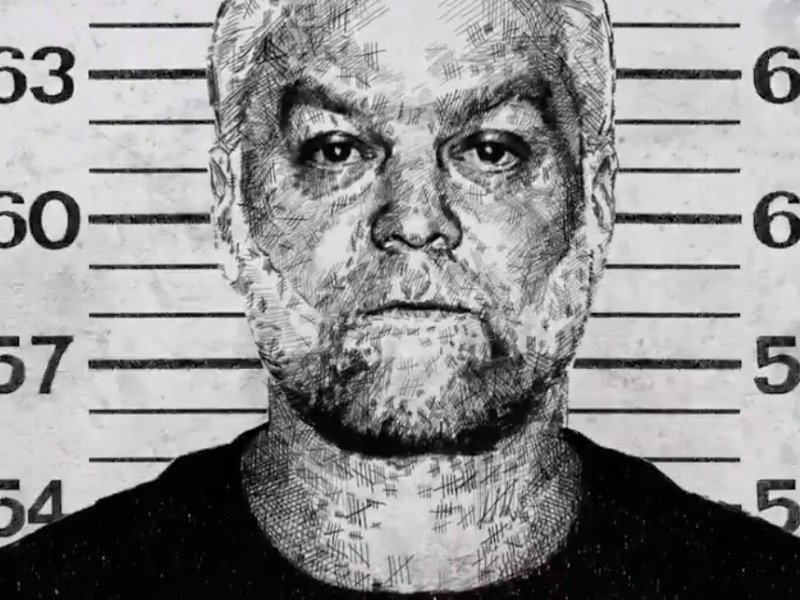

"Making a Murderer" chronicles the surreal story of Steven Avery’s exoneration of a rape for which he spent 18 years in prison and his subsequent conviction of the murder of Teresa Halbach, for which he’s now serving life in prison. It particularly focuses on Avery’s trial, raising serious questions not only about police procedure and suspect investigation, but also about the systemic, socioeconomic issues of criminal defense. By now, though, everyone knows that.

The web television series appeared on Netflix last month, one week before Christmas. What took documentarians Laura Ricciardi and Moira Demos 10 years to fastidiously film and painstakingly produce was, within days, binge-watched by millions, thanks to critical acclaim and breathless word-of-mouth and social-media buzz. America collectively injected itself with the compelling thriller, streaming the 10 hour-long episodes and then satisfying cravings by discussing the show on social streams and consuming all content that concerned it.

This website provided plenty; it was often the vanguard of original information in the wake of the documentary. And while countless hours spent poring over courthouse records and interviewing jurors unearthed more shadiness than even "Making a Murderer" had portrayed, three days in the county also revealed other details – strong distrust of the media, sad weariness of the story, a sense that the area wasn’t fairly depicted and, most fundamentally, the feeling that the series was a work of fiction that didn’t change many minds in Manitowoc of Avery’s original, enduring guilt.

Across the street from where Avery was convicted of the 1985 first-degree sexual assault of Penny Beerntsen – and freed in 2003 through DNA testing – is the Courthouse Pub, an upscale restaurant where men in suits drink bourbon, women wearing scarves sip red wine and the dinner entrees are all at least $20. The Wi-Fi password is "innocent" (the staff insists it’s been such since before the documentary) and the bill comes in a parking-ticket envelope that gives out-of-towners a brief scare.

Eventually, after phone numbers are looked up and dialed and voicemails reveal "memory full," a couple of reporters decide the only recourse is to drive out to the Avery property at night and knock on the door, a last-resort journalistic tactic that’s detested even by people who haven’t had to deal with unrelenting press for a decade. They also decide that a Swiss Army knife will be brought along.

The drive from downtown Manitowoc (population: 33,736) to the property is 25 minutes – a distance that doesn’t really come across in the documentary, which presents a meddling sheriff’s department and a troublemaking family as constantly tangling in each other’s close-by affairs. In reality, the reclusive Averys live 15 miles away and, while deputies do have jurisdiction in Mishicot, there are only a few to patrol a vast area; it’s not as though they’re waiting in squad cars down the block to ambush a lingering, preying Avery. Spatially, Manitowoc is larger, more developed and much more spread out than it’s depicted in the documentary – not surprising since most of the series' action takes place in just a few locations.

Eventually turning onto Avery Road, past the Auto Salvage sign that’s become a destination point for sight-seekers and proceeding toward the cluster of meager buildings, headlights vaguely illuminate a line of broken-down vehicles, giving the place a graveyard feel unrelated to its violent past. Parking in front of the home of Allen and Dolores Avery, Steven’s parents, a fingers-crossed knock on the trailer door brings an unexpected sight. Rather than an angry rebuke or no answer at all, it’s Mrs. Avery standing in the entryway, surprised to see visitors at 9 p.m. on a Wednesday, but not actually upset.

She looks exhausted, more worn than in the documentary, and doesn’t say much – watching and nodding as reporters hastily, apologetically explain why they’re at her door. After mentioning that she’s about to go to sleep, Dolores Avery listens to a pitch for a sympathetic interview and agrees to meet on Saturday, after the business closes. But the next day, Steven Avery will get a new legal team that forbids the family to talk to the press, thus leading to Charles Avery saying his mother "must’ve misunderstood" and sternly instructing the visitor returning on Saturday to "hit the road!"

Upon leaving, the next trip is to the residence of Barb Tadych, Steven Avery’s sister and the mother of Brendan Dassey, who was convicted of assisting his uncle in Halbach’s murder but whose case is now in federal appeals court. The house is completely dark, so a call is made instead. Unexpectedly, Tadych answers and, after initially saying she can’t talk about legal proceedings and also has to wake up early, remains on the phone for a poignant 10-minute conversation.

Tadych sounds forlorn and fatigued but also seems to recognize the opportunity to send out a message. She says she doesn’t trust the media because, "Last time, they only told the other side." When asked about her side, especially her position within and feelings toward the family, she replies with a mother’s stridency. "The truth has to come out," she says. "My son didn’t do it, and neither did my brother."

A mile east on Main Street in Mishicot, at Crow Bar & Grill, where there’s a box of $1 candy bars fundraising for the Pediatric Brain Tumor Foundation and the clientele’s attire ranges from camo and overalls to NASCAR jackets and Packers sweatshirts, Tadych’s neighbors believe the opposite.

"Steve Avery was nothing but trouble since the day he was born," says one 44-year-old who wishes to remain anonymous. "It’s a junkyard family. I don’t know how else to put it. They all live very close together, but no one likes each other."

The man hasn’t watched the series and is "getting sick of people talking about it at work," but he remembers the case well and speaks about it with impressive acumen. He asserts that the anachronistic Averys aren’t so much shunned outcasts, like the documentary might suggest, as non-integrative loners, stuck in a place out of time and unwilling to fit in or adapt.

"Nobody really knows the Averys, but what we do know, nobody likes," he notes. "That’s just the general feeling because of their reclusiveness. They very much kept to themselves. They still very much do, which is part of the stigma. I’ve lived here 19 years and never met any of them."

With a crossbow hanging from the ceiling over her head – part of the Crossbow Raffle – a bartender who also doesn’t want her name used expresses contempt for the documentary, which she always refers to with air quotes. "The only reason the story is getting so big is because it’s so one-sided, and people don’t know what they’re missing," she says. "If you watch that documentary, you’d have to believe he was framed. But anybody with half a brain can see it wasn’t the whole story."

The bartender, who says she watched the entire series in one sitting and got a parking ticket because of the all-nighter, grew up in nearby Two Rivers and has met two Averys. It's apparent she's seen her fair share of police procedural dramas on television and admits the Manitowoc sheriff’s department’s handling of the investigation "raised questions," but she still doesn’t believe Steven Avery was framed.

"The whole thing is stupid. He’s in jail for a reason," she says. "A lot of people in town are watching, but I know a lot of people won’t watch it, too."

As locals chatter about it, TV news reports about the Avery case come on twice within the hour. The bartender, who notes it’s all anyone talks about in the pub and on Facebook these days, says, "We all just wish this would go away."

Echoing that sentiment, the beer-drinking regular says he’s tired of hearing about it, but knows the "sh*t-storm" isn’t ending anytime soon.

"Welcome to Mishicot. We almost never talk about the Averys," he says. "Until dipsh*t killed a girl, and then not again for 10 years until this Netflix thing."

He continues, "This isn’t the kind of attention that anybody wants for their hometown. You guys are just the beginning. It’s going to get a lot worse before it gets better."

No matter where you come down on Steven Avery’s guilt or innocence, Brendan Dassey’s involvement or manipulation, the sheriff’s department’s ineptitude or misconduct, the legal system’s effectiveness or failure, one truth that’s clear in all of this is that no one in Manitowoc County is benefiting from the situation.

The frenzy, the interest, the excitement – it’s all online, though increasingly at Dolores Avery’s door or in the local tavern or the county courthouse. The Internet’s giddy phenomenon is Manitowoc’s unhappy reality.

Externally, a pair of gifted filmmakers did the documentary of a lifetime, Netflix got one of the biggest streamed series of all time, millions of spellbound viewers were entertained, the media capitalized on the story with endless content and several lawyers made money and a name for themselves.

In Manitowoc, besides the obvious victims and their families – the Halbachs and the Averys – the region’s reputation has been damaged, law enforcement and the courts have taken a beating, regular people have had to defend where they live and folks are putting up with bothersome reporters buzzing around.

Nowhere is that last problem more evident than at Beernsten’s Confectionary, a homemade candy shop on 8th Street in downtown Manitowoc. Founded and owned for years by the family of Penny Beernsten, the woman whose rape resulted in the 1985 conviction of Steven Avery that would later be proved wrongful, the beloved store was sold in 2003 to Dean Schadrie.

Unfortunately for a visitor unaware of the company history who’s curious whether the documentary has had an impact on business, a short-haired woman with an even shorter temper senses snooping and snarls, "The Beernstens don’t own this store, and they haven’t for 12 years. If you’d done your research, you would have known that. Please leave now."

Just a few blocks away, however, another area businessperson is less irascible in discussing the documentary and its effects on the city.

"I just feel bad about all of it," says Paul, the general manager of the Legend Larry’s location in Manitowoc. "I don’t really have an opinion on it one way or another; I wasn’t here when it all happened. But the Halbach family …

"It’s being sensationalized now. I’m surprised there aren’t T-shirts yet, ‘Free Avery.’ Those are coming."

He says he’s gotten private investigators from Oregon calling the restaurant and making inquiries. "People here are just tired of it," says Paul, who was born in Manitowoc but gone for more than 30 years, living and working in Indiana, Florida and Milwaukee during the years of the Steven Avery cases.

"I’m from here, my wife is from here, we like it," he says. "It’s a small town, but it has good Midwestern values and good people."

When asked about the business climate in his hometown, Paul says the number of bars has been cut in half since he left, from about 130 to about 65, "which is good." But he also talks about the loss of blue-collar jobs and, puzzlingly, the dearth of qualified applicants for remaining positions. "I’ve talked to a bunch of guys who just can’t pass the piss test," he says, which is hurting Manitowoc’s forward progress.

A shipbuilding hub since the mid-19th century, Manitowoc has a rich nautical history and is home to the Wisconsin Maritime Museum and a multimillion-dollar marina complex on Lake Michigan. The city’s industrial segment took a hit in 2003 when the Mirro Aluminum Company closed, but it still boasts major manufacturers such as The Manitowoc Company and Briess Malt & Ingredients Co., whose gigantic concrete silos have massive Budweiser cans painted on them, forming a boozy, Americana backdrop to the downtown.

One person who is remarkably unconcerned with how "Making a Murderer" has affected Manitowoc is the mayor of the city, Justin Nickels. The 29-year-old incumbent, who was first elected in 2009 at age 22, sits back in his chair in a well-appointed office surrounded by framed photos of him playing with kids and posing with Scott Walker, appearing relaxed, self-assured. Or at least resigned to what’s happening.

Starting his answer with a long sigh, he says the "thriller" – he won't call it a documentary – is not something the city is focusing on for a couple of reasons.

"One, it’s out of our hands completely; and two, in our minds, it will blow over," Nickels says. "I’m sure the community that Charles Manson was born in got a bad rap, too, but why? This community is 35,000 people; it’s not this Netflix thriller that’s making the community of Manitowoc. We know who we are and what we have here, and once all this blows over and there’s another one that TBS makes on a different place, that’ll be the next buzz."

Nickels says he actually enjoyed some aspects of the series, including the "beautiful views" of Manitowoc’s downtown and lakefront, though he issues a reminder that the city’s only real role was housing the courthouse and the jail.

He doesn’t think "Making a Murderer" will hurt tourism or local business, and he’s not really sure what could have been done to prevent any such problems anyway.

"It makes us look bad, there’s no doubt," Nickels says. "But I think rational individuals would understand that, again, it’s not a community that’s the problem. I’m not even consuming myself with it because we have no control – I don’t, my administration doesn’t, we weren’t here when it happened.

"But even if I was in office when this happened, what would I have done anyway? The mayor has no control over the judicial system and shouldn’t."

It is entertainment, not reality, Nickels emphasizes. While Manitowoc doesn’t have the same reach or scope that Netflix has, no hours of footage to showcase how wonderful it is, he points to Forbes ranking it the No. 2 city in America to raise a family two years ago.

"I’m not worried right now that people aren’t coming to Manitowoc because they’re worried they’re going to get framed for murder," he says, "which is what some people are saying on Twitter."

Indeed, one does feel eminently safe leaving City Hall and traipsing along the picturesque river walk. Past friendly diners and cozy drinking establishments, past the docked submarine and the gleaming public library, past cutesy Main Street shops and the old-fashioned Capitol Civic Centre theater advertising a John Denver musical tribute, back to the grand Manitowoc County Courthouse that's right next door to the all-too-familiar sheriff’s department. A few people smile as they walk by, a church rings its bells on the hour, but otherwise there’s little local flurry – just the snowflakes starting to fall.

Though weary of the recent onslaught of unwanted obsession, the Manitowoc milieu remains quaint, tranquil, comfortable with what it is, as Nickels says. The people here will tell you they, and their county, are more than "Making a Murderer."

Upon returning to the Courthouse Pub, it’s almost hard to remember why this charming locale is the center of the pop-culture universe. But then, after logging onto the wireless network, using the password "innocent" and going online, about 184 million search results offer a crushing reminder.

An undesired reality

Born in Milwaukee but a product of Shorewood High School (go ‘Hounds!) and Northwestern University (go ‘Cats!), Jimmy never knew the schoolboy bliss of cheering for a winning football, basketball or baseball team. So he ditched being a fan in order to cover sports professionally - occasionally objectively, always passionately. He's lived in Chicago, New York and Dallas, but now resides again in his beloved Brew City and is an ardent attacker of the notorious Milwaukee Inferiority Complex.

After interning at print publications like Birds and Blooms (official motto: "America's #1 backyard birding and gardening magazine!"), Sports Illustrated (unofficial motto: "Subscribe and save up to 90% off the cover price!") and The Dallas Morning News (a newspaper!), Jimmy worked for web outlets like CBSSports.com, where he was a Packers beat reporter, and FOX Sports Wisconsin, where he managed digital content. He's a proponent and frequent user of em dashes, parenthetical asides, descriptive appositives and, really, anything that makes his sentences longer and more needlessly complex.

Jimmy appreciates references to late '90s Brewers and Bucks players and is the curator of the unofficial John Jaha Hall of Fame. He also enjoys running, biking and soccer, but isn't too annoying about them. He writes about sports - both mainstream and unconventional - and non-sports, including history, music, food, art and even golf (just kidding!), and welcomes reader suggestions for off-the-beaten-path story ideas.