On a recent, rainy Saturday in May – really, on any Saturday in the spring and fall – you could drive all around the greater Milwaukee area and see the happy fruits of Aleks and Helga Nikolic’s hard work, on display in ways not even they could have conceived of a half-century ago when they helped found the Milwaukee Kickers Soccer Club. And they conceived of quite a bit.

You’d see hundreds of kids at dozens of fields wearing those familiarly colorful, weekend-ubiquitous rec jerseys with "mk" on the front and "Kohl’"s on the back. You’d see competitive MKSC Academy teams, with their high-level staff coaches and sophisticated styles, battling the state’s best select squads in important league matches. You’d see Hmong-American children playing at 84th and Hampton, representing HAPA, Kickers’ brand new region and an example of its community outreach efforts. You’d see 24-year-old Uihlein Soccer Park, one of the Midwest’s finest facilities, hosting a huge tournament and thousands of people – and preparing for some exciting expansions.

You’d see boys and girls of all ages, races, backgrounds, sizes and abilities playing, laughing and learning together; you’d see parents huddled next to each other, holding cups of coffee, yelling words of encouragement and devoting time, effort, oranges and dollars to this thing. You’d see staff and volunteers making sure it all ran smoothly, week after week, year after year, this uniquely unifying force and community-enrichening entity that is the Milwaukee Kickers Soccer Club.

What started as a simple yet radical idea of the Nikolics and their friends in the basement of a house on the near South Side in 1968 has become one of the largest and most respected youth sports organizations in the United States. The Milwaukee Kickers serve more than 8,500 kids annually in 15 regions, ranking among the top soccer clubs in the country based on current membership. Uihlein Soccer Park hosts six high-profile major tournaments and scores of other events, attracting more than 600,000 visitors every year to its three indoor and 13 outdoor fields.

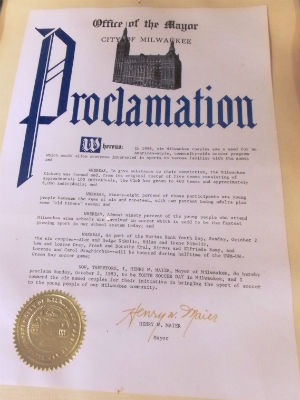

The club has received mayoral proclamations and international recognition, hosted the U.S. Women’s National Team and sent its own squads to play abroad. It’s propelled players to college on soccer scholarships and helped improve the lives of underprivileged kids through its America SCORES program. It’s grown, expanded and flourished, contending with changing attitudes and challenging realities, while staying true to its values and instilling a lifelong passion for the game.

And it all began with one basic belief: everyone should be able to play soccer, no matter your skill level or gender. That was the original mission of the Milwaukee Kickers, its impetus for forming 50 years ago.

* * * * *

Soccer was hardly a popular sport in the U.S. in the mid-20th century, played mostly by pockets of immigrants and their families on ethnic-oriented teams. Some of the oldest and most successful amateur clubs in the country were from Milwaukee – the Bavarians, Croatian Eagles, Sport Club and Milwaukee Serbians – but their proud ethnic traditions served to de-facto preclude many American players and keep the game out of the mainstream.

Aleks and Helga Nikolic, immigrants from Yugoslavia and Germany, respectively, saw the new American friends of assimilating Serbian kids being rejected by the club’s leadership, saw girls being excluded, and they wanted to do something about it.

In 1962 the Wisconsin Soccer Association launched a youth program with the Milwaukee County Parks & Recreation Department, and, within a half-dozen years, soccer had become the park system’s second-largest participation sport. Recognizing the growing interest and involvement, but lack of opportunity, among American children, a group of local soccer advocates – six married couples, 12 people; five from Yugoslavia, three from Italy, three from the U.S. and one from Iran – decided to try developing soccer another way.

Everyone would have a place and a chance to play, they said, boys and girls alike; they would provide good coaching and stable administration; and, most importantly, there would be strong family involvement, which would produce an active volunteer base to operate the club.

"When we started to plan this thing, I went and watched other sports leagues," Aleks Nikolic says. "They would not allow parents around, good kids played and not-as-gifted kids were sitting on the bench. I said, OK, we have to be different than that. You have to play the kids at least 50 percent and parents have to be involved.

"We changed the culture in this community of how people do things. We changed it with our approach, because we said kids are going to play half a game. I think that was one of the key moments. And the other one was bringing the girls in. When they come in, it exploded."

At the time, 30-year-old Aleks Nikolic was head of the youth program for the Milwaukee Serbian Soccer Club and, while his initial request to form his own club was met with amused indifference – everybody plays half the game? Girls get to play? Good luck! – the relationship soon turned frosty. The Nikolics were perceived to have turned their backs on their Serbian identity and culture; they were practically excommunicated from the church, they joke, and the next 20 years were fairly unpleasant.

"It’s so ironic; everybody was an immigrant," says Helga Nikolic, then a schoolteacher. "They wanted to keep their culture alive, and (soccer) was an offshoot of that identity, but sooner or later – come on, think a little bit, you’re gonna be an American.

"Soccer is not going to get bigger if you keep it isolated. And certainly kids are not going to stay in their little bubbles. It really took off because kids saw this was a great game, but if you’re stymied because you’re not Serbian and you can’t be on the team, then where are you going with it?"

In November 1968, the founders met in a basement and organized the Milwaukee Kickers. Their vision: to attract, develop and retain soccer players of all ages and abilities without regard to gender, race, national origin, religion or socioeconomic status.

After picking a slogan, "American Soccer is Our Goal," and choosing red and gray as the club colors, Nikolic’s group appeared in front of the Wisconsin Soccer Association members for authorization to launch. Milwaukee Serbians voted against but Bob Gansler’s Bavarians voted for them, among others, and the Kickers were narrowly approved by one vote.

The 12 founders – Aleks and Helga Nikolic, Lorenzo and Carol Draghicchio, Lew and Louise Dray, Frank and Dorothy Kral, Milan and Irene Nikolic, and Sirous and Elfriede Samy – rejoiced, and then quickly set to work.

* * * * *

In 1969, its first year of operation, the Kickers had 78 players on five teams, including four youth squads, playing weekly recreational games outdoors. On the contemporary American soccer landscape, still dominated by sequestered, talent-rich but participation-poor ethnic clubs, Kickers was revolutionary and rare – many think it was the first organization of its kind, at least in the Midwest.

"The most vivid thing to me is that everybody made the time," Helga Nikolic says, remembering hours spent at the various founders’ homes. "We had these meetings, and we just hashed everything out. This is important; if we don’t do it right now, it’s not going to last.

"We had the organizational model of the immigrant clubs at the time, which were sort of in disarray, so do something different from that. I think that’s what our model was: don’t do that. And then we got people involved who were in business and had different expertise, and it became more structured, organized. By just working at it, we figured out the best way to do it."

Success soon followed – on the field and in the community – as young families were drawn to Kickers’ progressive philosophy, model and structure, and the club experienced enormous expansion in its first decade. Parents liked that they could be part of the program instead of outside it, and their close involvement ensured a vested interest in Kickers’ advancement.

After becoming a not-for-profit Wisconsin Foundation in June 1970, the club grew from seven to 280 teams by 1979. It presented college scholarships and became involved in Milwaukee Public Schools leagues; developed the Milwaukee County Women’s League, the state’s first youth girls league and an "Old Timers’ League"; it organized family events, launched a monthly news magazine called "KICKS" (published almost singlehandedly by Helga Nikolic), and operated youth clinics, camps and indoor programs. It established its own staff of licensed United States Soccer Federation coaches and referees and improved administration issues like scheduling and transportation.

In 1978, MKSC partnered with Waste Management to utilize land at N. 124th St. and W. Brown Deer Rd. for the "Kickers Sports Center" complex – an experiment in the recreational use of a landfill.

Kickers’ approach was groundbreaking for American soccer, but it was hardly an inimitable system. So why wasn’t anyone else doing what they were doing at the time? "Because it was a lot of work, a lot of effort, a lot of time away from other things," Helga Nikolic says.

Adds Aleks, "Because they didn’t think of it. And by the time they did, it was like, ‘Well, let’s just join the Kickers.’"

In the 1980s, MKSC expanded its reach into high school programs and new communities. As the fledgling sport continued to find new fans, the Milwaukee-based club’s membership extended, incredibly, up to Sheboygan County and out to Beloit – more than 350 total teams – though its Wauwatosa and Whitefish Bay regions remained its strongest.

Kickers leadership fostered all sorts of important connections, with Milwaukee politicians, judges, businesspeople and philanthropists, but the club’s "KICKS" magazine and its members in the media were particularly influential in telling the public that soccer was becoming an American sport and Kickers was the place to play it. Every time a Milwaukee Sentinel reporter wrote a story about Kickers, Aleks Nikolic says, they’d get another 500 kids. Delighted families’ word-of-mouth advertising was just as beneficial.

"What stands out is the enthusiasm of the people that started this," Helga Nikolic says. "It was contagious, like, ‘What about this? Let’s try this.’"

Still, with growth came growing pains, as "We Are The Kickers" put it. Some geographic groups splintered off to form their own clubs, starting with the Brookfield Region in 1981 and continuing with Ozaukee County and other exurban areas in later years. Aleks Nikolic says Kickers became such an incubator for youth soccer development that individuals felt they could replicate the program outside the MKSC structure, building new clubs on its principles of inclusiveness and volunteerism.

"They would separate and then do the same thing," he says. "That’s OK; they just wanted to run it. Imitation is the most sincere form of flattery. We must have been doing something right."

Meanwhile, not everyone was convinced of the altruism of Kickers and the Nikolics. Once, Aleks says, he was investigated by a Milwaukee Journal writer who couldn’t believe there wasn’t an ulterior motive to the tireless, unpaid volunteering behind the emergent club. Aleks went to the writer’s office, asked him to look through the books and invited him to speak at the next Kickers banquet. The two are friends today.

"It sounds really idealistic: ‘Look at these people, they wanted to do this for the good of the community.’ But we did," says Helga Nikolic, who didn’t have kids of her own until Kickers was a few years old. "It’s hard to believe, but it was so exciting. I don’t know, it just made you feel really good, so we kept going and we saw that this was something that was needed.

"Why were we the ones to do it? Obviously, no one else was picking up the ball. I think really it was a vision. It wasn’t just, let’s do this for a while and get our kids in it, but what can we do to make this a better community?"

* * * * *

Early on, the established clubs scoffed at Kickers’ recreational model, viewing their teams as non-threats. But as knowledgeable coaches like Nikolic taught and developed their armies of players, MKSC youth select and adult majors teams improved rapidly.

In the late-1980s, Kickers teams coached by Nikolic – featuring stars like Mike Huwiler – were among the best in the Midwest. By the 1990s, the Milwaukee Kickers Nationals, led by professional coaches from Europe, was arguably the top program in the state. In 2009, the U-20 Kickers won the United States Adult Soccer Association's national championship. And today, the MKSC Academy, which has become one of Wisconsin’s leaders in youth soccer development, continues Nikolic’s educational legacy, with elite coaches instructing players in the tactical, technical, physiological and psychological aspects of the game.

From the beginning, Kickers’ administration set it apart from other clubs too. Most of the original founders stayed actively involved for Kickers’ first 15 or so years, including Helga, and they established a coherent organizational structure, with a board of directors, club president (on a three-year term), general manager, director of coaching. Soon, an administrative assistant and accountant were hired, and later a dozen more staff positions would be added. Aleks Nikolic remained a key figure for decades, serving as MKSC president, general manager, director of coaching and staff coach over the years. In 1986, as dining room tables overflowed with registration forms and basements were stacked to the ceilings with jerseys and equipment, the club moved to a real office, streamlining operations. More change came not long after, when the Kickers Sports Center, which had seen increased use and received maintenance and facility improvements, started reminding everyone it was a converted landfill.

"One day, green stuff started oozing out of the ground," Nikolic remembers. "I said, I've got to find another place." Despite buzzing with activity, Waste Management closed the site for environmental reasons, forcing Kickers to search for a new home. It would end up being a blessing in green-ooze disguise.

While groups of volunteers and club officials explored available space for a new soccer park – Kickers membership stretched from Sheboygan to southern Milwaukee County and west into Waukesha and Washington Counties, so a geographic center was the goal – Nikolic drove every day to work at 51st and Good Hope.

On the way, he’d pass by the Milwaukee Polo Field, part of the Uihlein Family Trust land owned by Laurie Uihlein, and one day he noticed it was empty – the Polo Club had moved its headquarters. Nikolic brought up the vacant Polo Field at the next Kickers board meeting, and one of the members mentioned he was married to an Uihlein. Through that connection, the club convinced the Uihlein Family Trust to let it use and maintain the existing fields with an option to purchase the land.

"You start realizing all the connections, and it was sort of lucky," Helga Nikolic says. "But also the reason all these people were together is because of this thing that they all believed in."

Over its 20-plus years of existence, the Milwaukee Kickers had morphed from a mom-and-pop soccer club to a multi-million dollar organization, but, after receiving their first tax bill for the new land, they realized they still weren’t in any position to pay for it – much less build the permanent, indoor-outdoor complex they wanted. Still, what Kickers lacked in dollars, they made up for in good ideas. With the backing of the Uihlein Trust, they decided to donate the land to Milwaukee County.

Two local law firms performed pro bono work to help resolve tax and environmental issues on the site, while Kickers board leaders George Farley and Floyd DeBow worked with County Executive Tom Ament, as well as County Supervisors Roger Quindel and Lee Holloway, on a deal for the land. The Milwaukee County Board issued a 20-year bond to purchase the polo fields land and build a facility, with the Kickers agreeing to annual $500,000 debt service payments and to provide programming for "minority and other groups" in the urban area where the new soccer park was located.

After Milwaukee County purchased the land, a Kickers ad hoc committee worked with Uihlein Architects and the County to plan the property. In 1994, with the help of its partners, Kickers built Uihlein Soccer Park – complete with administrative office, three indoor fields, locker rooms, concessions, 13 outdoor fields, parking lots and more – and it’s been a jewel of Wisconsin’s youth soccer community ever since.

* * * * *

Over the course of its 50 years, Kickers has processed at least 200,000 kids – and that’s a conservative estimate, according to club officials. Soccer is the third-most popular youth team sport in the United States, by participation, and if you know someone in the area who’s played the game, chances are they’ve worn the "mk" jersey at some point.

One of Wisconsin’s most accomplished players has warm memories of her time playing for the Milwaukee Kickers. Leslie Osborne, a retired professional and former member of the U.S. Women’s National Team who appeared in five games during the 2007 FIFA Women’s World Cup, grew up in Menomonee Falls and played for the Kickers from U-11 through U-20.

"Some of the best memories of my childhood and soccer career are from playing on those Kickers teams," Osborne says, mentioning her "amazing" and "special" coaches – David Nikolic, Mark Lambrecht, Pete Knezic, Rob Harrington and Tony Wright. "I loved coming to the fields multiples times a week and every weekend, playing against the older girls and the boys, and I loved indoor. I feel so fortunate; I was challenged in different ways."

What stands out now, 15 years later and with a breadth of international and club experience, about the Milwaukee Kickers?

"The people, hands down," Osborne says.

Aleks Nikolic recalls taking teams to Europe and telling incredulous club officials there about Kickers’ model and membership. "I think at one time, we were maybe the largest club in the world," he says. "I don’t have any way to prove it, but I’m guessing, because of our makeup and the rest of the world didn’t do it like we did."

MKSC’s high-water mark was in the late 1990s, when the club counted upwards of 13,000 youth in its rolls, according to membership services director Nancy Ziaja, who’s been with the club since 1988. She remembers the 90s as Kickers’ vibrant, halcyon days, when numbers were sky-high, the Milwaukee Rampage professional team played at and drew big crowds to Uihlein, the organizational mission met kids’ desire to play and families embraced being involved.

"The presence in the community was really great. I think it was a lot more vast and wider than it is now, because we had a larger geographic area," Ziaja says. "And, of course, volunteerism at that point in time was at its heyday. Everybody wanted to volunteer. Things ran, I think, a lot smoother than they do now."

Ziaja and Kickers Executive Director Alvaro Garcia-Velez, at their Uihlein Soccer Park offices, say operating the club presents different challenges today, thanks to technology, parental involvement, kids’ activity, and shifting priorities and expectations.

"Society’s changed," Ziaja says. "The same people that volunteer at church, at scouts, for music recitals, they’re the same people that volunteer for soccer? So, they're stretched pretty thin. It’s fragmented. Both parents work now, where back in that day, there were a lot of stay-at-home-people."

Long the lifeblood of Kickers, volunteerism has stanched. "That’s not specific to here, but it’s becoming more and more difficult to find that really committed person," Garcia-Velez says. With volunteer buy-outs, parents will often just write a $75 check to pay the fee, rather than actually volunteering for the club.

Steve Harris, current president of the board, agrees. "I’ve seen parent involvement become tougher to find in the last 10-plus years," he says. "When Aleks and Helga started the club, there was a strong sense of pride, uniqueness and inclusion that helped bring passionate people together who wanted to make a difference and see success. Today, it can be harder to create that strong sense of pride and passion in the club."

Ziaja mentions how regions used to hold fun registration nights, when a regional director would host a party-like event to bring families together and get kids signed up.

"Because of online registration, everything's computerized, everybody's got a phone and they want to get instant information, you've kind of lost that personal touch," says. "I think society now has turned that corner, where … they’re so busy, they just want it right away."

Looking back over the past five decades, Helga Nikolic has seen a similar trend.

"I’m just thinking about how everybody who got involved was committed to it. There was a loyalty, a sense of this is important," she says, adding that every parent had a job, some kind of buy-in, no matter how seemingly insignificant. "I don’t know; were people different? Now it’s kind of, ‘I don’t need it.’

"We wanted to provide something good for kids they weren’t getting from other venues."

That’s another issue. For many years, Kickers was doing something other organizations weren’t, and they were doing it well. MKSC is still functioning at a high level, but new clubs have sprouted and other sports have adopted the approach.

"Back then, we were the only club in town," Ziaja says. "And, everybody has really caught up to us. When we started out, we were the only game where kids could play at five, six years old. Now, every sport goes down to the pee-wees."

Bringing up another problem, Garcia-Velez points to declining youth athletics participation overall.

"I think kids are also less active, with video games and phones," he says. "They finish their homework, their parents are at work so they can’t go outside, and they sit on the computer. It used to be, go kick a ball and run around. … I think you're going to see the numbers in youth athletics continue to drop, maybe 6, 7, 8 percent a year."

But the long-tenured Ziaja and Garcia-Velez, who’s in his 10th year as executive director, as well as the rest of the 15-person full-time staff and countless others, continue to see Kickers’ worth and know how it impacts the Milwaukee community.

* * * * *

Soccer remains one of the most affordable youth sports, and at the noncompetitive recreational level – mostly played by kids from U-6 to U-10, which comprises the majority of MKSC membership – nobody does it better than Kickers, Harris says, thanks to their infrastructure, organization and experience. The Kickers’ base registration fee is $140 for the year, which includes eight games in the spring and fall, plus a uniform. Besides the two seasons of scheduled league games, MKSC teams also can play indoor during the winter.

"We do the recreational program very well. That's sort of the bedrock – that's what we're known for, and we tend to get in trouble when we try to do more things," says Garcia-Velez, who completed Harvard Business School’s Strategic Perspectives in Nonprofit Management program and brings a fiscal responsibility and budgeting background to the club. "To me, there's a lot of value added on that side."

Kickers serves thousands of kids through its rec program, but, despite a Midwest Region in the Washington Park area, the club has long struggled to operate in the inner city. Aleks Nikolic says that was "the only place where the model didn’t really work because … the parental support, the way we’re based with volunteerism, it just wasn’t there." However, in 2004, Kate Carpenter helped the club figure out an effective way to get into the central city and creatively serve the community’s neediest children.

America SCORES Milwaukee, an affiliate of the national SCORES network and the Kickers’ community outreach arm, provides high-quality afterschool opportunities to thousands of underprivileged local children using soccer programming, creative writing and service components. Since Carpenter launched America SCORES Milwaukee 14 years ago, it’s expanded from 40 kids at one school to 2,000 across 25 schools, inspiring inner-city youth to lead healthy lives, be engaged students and have the confidence and character to make a difference in the world.

"We're using soccer, poetry and service to provide kids a safe space with a caring and trusting adult, give them positive things to do after school and continually connect back the positive attributes that each of those play in one's life," says Carpenter, noting the SCORES kids’ improved attendance compared to Milwaukee Public Schools’ rate. "Academics, sport, physical health, giving to your community, all of those things rolled into one over time – the kind of person that you're going to be and understanding how you work in the world." America SCORES isn’t Kickers’ only outreach effort – the two organizations also collaborate on CityKicks, which similarly provides soccer-based youth development programming, MKSC partners with TOPSoccer to support athletes with disabilities, and the staff volunteers and donates time extensively in the community – but Carpenter’s initiative is by far the most impactful. It’s an intuitive, mutually positive relationship, she says.

"We probably have the sweetest deal that any two non-profits could have, because we're here for kids, and it happens to be around soccer," Carpenter says before the annual SCORES Cup. "For us, the benefit is that the dollars we raise go to the program, which is great. And the organization says, ‘We believe in this; soccer for social good is just as important as pay-to-play.’ We have some SCORES kids that are on the youth Academy teams here. We're always trying to keep both parties connected and engaged to make sure that we're able to serve as many kids as we can.

"We’re the only ones (nationally) that have this model. It really is interesting. People try to figure it out. But there's not an entity as big as Kickers in other states. … That partnership for us has definitely been invaluable. I can't imagine it really any other way and, lucky for me, I don't have to."

Another example of Kickers’ innovative outreach is the club’s newest region, based out of the Hmong American Peace Academy. The relationship formed in 2017 when SCORES was doing P.E. support at Wisconsin’s first Hmong charter school and learned the kids didn’t have a place to play organized competitive soccer. Within a year, Kickers went from donating goals and Uihlein field time to incorporating HAPA as a full region.

"I don't know of any other club in the state that does anything like that – that reaches out to the community, find out what it needs and actually helps get the program started," Ziaja says. "And, their school is huge. It's a great partnership."

This is HAPA’s first official season, helping to offset the loss of two regions, Greendale and New Berlin, which left Kickers this year.

"You've got a lot of people here who care deeply about community and community involvement and giving back," Ziaja says. "Kickers in the community, some of the things the staff does, above and beyond that are not soccer-related, it’s really impressive."

* * * * *

Milwaukee Kickers Soccer Club is a 501c3 organization, motivated – and obligated – to give back to the community, program for underserved youth and ensure fair, equal and affordable access to the sport for all. But outreach costs money; free programming is never truly free. And that’s to say nothing about the expense of running a full-service club with 8,500 active members, doing all the unsexy-but-essential administrative stuff like uniforms, insurance, referees and scheduling that are often unappreciated.

How does MKSC manage?

It’s not easy, Garcia-Velez says. Local foundation money has dried up, sponsors are fewer and longtime partners are giving less – perhaps some recognize that, even if they get a million ad impressions by having their name on the back of Kickers rec jerseys, not many bank accounts are being opened because of it.

The solution, increasingly, is Uihlein.

Ziaja, Garcia-Velez, Carpenter and the Nikolics all point to the acquisition of the soccer park as a major milestone for Kickers. Harris says completing negotiations with Milwaukee County on a new 30-lease for the park in 2015 was "the most significant challenge" he’s faced as board president, but also one of the biggest achievements, as it positioned the club to plan for future, long-term investments. Each of those stakeholders has standout memories of Uihlein – the U.S. Women’s National Team playing there, Rampage championship games, high school state tournaments, Kicknic events.

But to be the financial engine Kickers needs, they say, Uihlein has to do more.

"You have two very separate entities: you have the park, which is the for-profit arm, and then you have the club, which is a non-profit arm," Garcia-Velez says. "And they have to be in this harmonious relationship that is not harmonious at all, because the club wants to use the park all the time for free and the park needs to make money, so they’re sort of at odds in their relationship."

Adding the two outdoor turf fields "has been huge," he says, enabling teams to play in bad weather and avoid cancellations, while also allowing for different programming. Uihlein has hosted lacrosse, kickball, curling, ultimate Frisbee, field hockey and youth football events. The indoor facility has been rented out for a dog show.

"For us it’s important," Garcia-Velez stresses, "this is not just a soccer park. We want it to be a great community resource that a lot of people can use."

But that can be a "slippery slope," he adds.

"You've got this wonderful park, but it costs a lot of money to run," Garcia-Velez says. "We're constantly in this battle of, do you give fields away for people to use them? You want to make it cost-effective; what's our tipping point? If we have too much free use, then we can’t break even. … At the end of the day, we’ll end up giving them away, though."

With a resilient smile, Ziaja adds, "We always find a way to make it work."

Recently, Kickers has been exploring new and exciting ways to make it work. The club is currently in the process of finalizing with the state Department of Natural Resources an acquisition of 17 acres of contaminated land south of the park. Once approved, and after cleaning up the former dumping site, Uihlein could add three more full-sized pitches, plus another parking lot.

Garcia-Velez says MKSC is looking into other expansion opportunities, including options on the South Side for its teams in that area. "We’re also thinking of adding a beer garden," he says, "off the back end of the stadium, so it can oversee the field."

The biggest news for Uihlein, though, is the planned construction of a domed, full-size turf field – immediately south of the indoor building, adjacent to the stadium – that will allow for year-round play and potentially be a revenue-generator for the club.

"I think it's a game-changer," Garcia-Velez says, comparing it to Marquette University’s seasonal bubble at Valley Fields. The hope is to break ground by the end of the year, he says, "a pretty ambitious goal for us."

The project is expected to cost around $3 million, according to Garcia-Velez, and Kickers has been talking to several prospective sponsors. "Our business plan is the bubble supports itself and some revenue from the bubble goes right back into outreach," he says. "That's how we're framing it – to continue to have that outreach, and find a way to fund it."

MKSC has to frame it not only for the sponsors it’s pitching, but also its own regions. That’s because often people will see the club improving Uihlein and want to know why it’s not investing in their regions. "The park is the park, and it makes money to reinvest," Garcia-Velez says. "The club doesn’t make any money, so it has to take money from the park to invest into the regions."

That hasn’t always been a well-received sell, but it’s the reality, and members’ understanding that a moneymaking Uihlein helps everyone is starting to improve.

"When we first built the park, the club had to support it, with the hope that eventually the park would be able to support the club," Ziaja says. "And we're seeing that turn now."

* * * * *

For 50 years, MKSC has been a pillar of the local sports community, developing youth and providing people of all ages, backgrounds and abilities the opportunity to learn, play enjoy the game. Kickers has grown remarkably since the 12 founders created it in 1968, from a 78-player operation run out of basements to a sprawling club with 13,000 members and a landfill for a home field to, today, a professionally run nonprofit organization serving more than 8,500 youth, plus many more through outreach and adult teams, and possessing Wisconsin’s premier soccer facility.

Much has changed over a half-century, of course, in society and soccer, technology and funding, traditions and attitudes. But Kickers’ mission, passion and commitment to growing the game and improving Milwaukee have remained the same.

"One constant that has always been there is kids playing soccer," Ziaja says. "It’s become a little bit more complex, but it's still soccer. It's not brain surgery. We're putting kids on the field and giving them a neon-colored jersey, and they love it."

The running joke in the office, Garcia-Velez says, is whenever a staffer is having a bad day, "you just go into one of the regions and watch kids play."

They won’t have to go into the regions to do that on June 9, when Uihlein hosts MKSC’s annual Kicknic, a giant club-wide party that will honor Aleks and Helga Nikolic and delight nostalgic old-timers.

"It's nice to have Aleks pop in every once and a while. He sometimes still thinks he's in 1977," Garcia-Velez says with a laugh. "But what they did was extraordinary. They took an idea and ran with it. I mean, look at what it's become. It truly, truly is amazing."

When the Nikolics helped start Kickers, they wanted a place where every kid could play and parents were involved. They hoped to do something good for the community and, while they claim they never imagined it would become what it is now, their house that’s literally filled with souvenirs, mementos, photos, documents, KICKS magazines, old newspaper articles and trophies – a museum to MKSC – suggests they may have had an idea.

"Opportunity and follow-through," Helga Nikolic says when asked why Kickers has been able to survive and thrive. "We never closed the door. We didn’t limit people."

The Milwaukee Kickers, the Nikolics admit, has been probably the signature enduring element of their marriage, a testament to the familial spirit of the club.

"One of the neatest things to think about is how many families and friendships were fostered by people just sitting next to each other on the grass, watching their kids, shivering in April," Helga Nikolic says. "People have said, ‘You guys have spent so much of your own money doing this,’ and we got to thinking, yeah, we could have had a vacation house!

"We have nothing, but we have everything. You know what I mean? We have such great memories; you can’t take that away."

In March, during his speech at the 2018 Wisconsin Soccer Hall of Fame dinner event, Aleks Nikolic asked the room of nearly 500 people how many of them had been involved in some way with Kickers. "More than half the room stood up," Ziaja says smiling. "It was really cool."

Nikolic gets that same feeling when he drives around Milwaukee, sees kids playing the game and thinks about all the soccer limbs that Kickers has sprouted here.

"It does sort of all come back," he says fondly. "I think it is a satisfaction that we did something for this community; we helped the community grow. We’re also thankful to the community, because we are immigrants and we’re thankful we are here. We feel like we kind of gave it back.

"It’s been wonderful. We’ve been so fortunate to go through this."

From left: Steve Harris, Nancy Ziaja, Aleks Nikolic and Alvaro Garcia-Velez

Born in Milwaukee but a product of Shorewood High School (go ‘Hounds!) and Northwestern University (go ‘Cats!), Jimmy never knew the schoolboy bliss of cheering for a winning football, basketball or baseball team. So he ditched being a fan in order to cover sports professionally - occasionally objectively, always passionately. He's lived in Chicago, New York and Dallas, but now resides again in his beloved Brew City and is an ardent attacker of the notorious Milwaukee Inferiority Complex.

After interning at print publications like Birds and Blooms (official motto: "America's #1 backyard birding and gardening magazine!"), Sports Illustrated (unofficial motto: "Subscribe and save up to 90% off the cover price!") and The Dallas Morning News (a newspaper!), Jimmy worked for web outlets like CBSSports.com, where he was a Packers beat reporter, and FOX Sports Wisconsin, where he managed digital content. He's a proponent and frequent user of em dashes, parenthetical asides, descriptive appositives and, really, anything that makes his sentences longer and more needlessly complex.

Jimmy appreciates references to late '90s Brewers and Bucks players and is the curator of the unofficial John Jaha Hall of Fame. He also enjoys running, biking and soccer, but isn't too annoying about them. He writes about sports - both mainstream and unconventional - and non-sports, including history, music, food, art and even golf (just kidding!), and welcomes reader suggestions for off-the-beaten-path story ideas.