Here’s a fun and easy indoor activity for today: Type "Milwaukee" into the search bar on your weather app. Cold, right? Yeah, winter sucks, but that’s not the point. Don’t actually push Enter; just type in "Milwaukee" and look at the suggested listings.

There’s Milwaukee, Wisconsin (woo!); Milwaukee Airport; you might see our incorporated cousins, West Milwaukee and South Milwaukee. And then there are a few imposters – or, perhaps more flatteringly, namesakes: Milwaukee, North Carolina; Milwaukee, Pennsylvania; even Milwaukie, Oregon. Huh?

This innocent little weather search was what initially piqued my interest about "other" Milwaukees. Were they named after ours? Like, on purpose? There are countless American cities named for their distinguished European counterparts by European-descended people, and there are far too many Springfields for whatever reason.

Madison, like numerous other Madisons nationwide, is an homage to fourth president James Madison; Green Bay was given its self-evident designation by early explorers more inclined toward observation than creativity. But what’s the deal with these non-Wisconsin, so-called Milwaukees/Milwaukies?

We grow up learning that our city’s name derives from the Algonquian language, an amalgamation of words for "good," "beautiful" and "pleasant land." Or, as Alice Cooper in "Wayne’s World" informs us: "it's pronounced ‘mill-e-wah-que,’ which is Algonquin for ‘the good land.’"

Regardless of the exact meaning, though, if Milwaukee is Algonquian – the subfamily of Native American languages spoken by the Menominee, Fox, Mascouten, Sauk, Potawatomi and Ojibwe tribes that first inhabited this area and definitively did not travel to North Carolina, Pennsylvania or Oregon – then it certainly must have originated here. Unlike all the European-inspired cities – like New York, New Berlin, Athens, etc. – Native American names tend to not reproduce elsewhere, for the basic reason that they’re regionally derived (and perhaps also hard to spell, read and pronounce).

For its first half-century after being founded in 1846, Milwaukee was a relatively large American city with a strong economy, thanks to its robust manufacturing and brewing industries. So, anecdotally, we can assume fledgling towns around the country might have looked at flourishing Milwaukee – with its unique, exotic-sounding name – as a place to honor. But ask John Gurda about that.

This isn’t really a story about the Milwaukee name or how other cities got to be called Milwaukee; it’s about the Milwaukees, themselves. In August 2016, Molly Snyder took a trip to Portland, Oregon, during which she visited nearby Milwaukie, a town settled in 1847 and named for the Wisconsin city that, at the time, was frequently also spelled that way. Molly "attempted to draw comparisons between Milwaukie and Milwaukee, and came up with very few similarities," but it was a good idea and a fun piece, and it reminded me of my weather-search curiosity. Later Molly writes, "We have now put Milwaukee, North Carolina on our travel bucket list to complete the Milwaukee-Milwaukie-Milwaukee trifecta."

I beat her to it.

Recently, I drove to Charlotte, North Carolina, to visit family, and afterward planned to go to Washington, D.C., to celebrate New Year’s with friends. When I saw that Milwaukee, North Carolina, was relatively on the way – it was only about 70 miles off the freeway, though it wrecked my precious hypotenuse – I decided I had to chart a route and check it out.

Before I left, I tried to learn as much as I could about Milwaukee, North Carolina, particularly its history and name. From my online reading, I found out that it is an unincorporated community in Northampton County and pretty much nothing else.

The county itself, while small (population: 22,099) was a little more noteworthy. Situated in the northeast corner of the state and immediately south of the Virginia border, it was formed in 1741. In 1959, Northampton County went to the U.S. Supreme Court to defend its use of a literacy test as a requirement to vote. In Lassiter v. Northampton County Board of Elections, the court held that, as long as the tests were applied equally to all races and were not "merely a device to make racial discrimination easy," they were allowable. Congress subsequently prohibited such tests under the National Voting Rights Act of 1965.

According to the 2010 Census, Northampton’s racial demographics were 58.4 percent Black or African-American, 39.2 percent White and 2.4 percent other. A traditionally heavy Democratic stronghold, Northampton is the only county in the United States – apart from several clustered together in South Texas – to vote Democrat at every presidential election over the past century. The last Democratic candidate to lose the county was William Jennings Bryan in 1896; only twice has a Democrat not received at least 61 percent of the vote. But back to Milwaukee.

While driving east on I-85, I called the Northampton County office for information. When I told the person on the phone I was from Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and – "this is sort of weird, but …" – I wanted to write a story about Milwaukee, North Carolina, I was met with a long pause and then a dubious, "You want to write about Milwaukee, North Carolina?" After explaining that it was just sort of a lighthearted piece about a place with the same name and, hey, maybe there were some fun similarities, she seemed convinced that my intentions were as harmlessly stupid as I assured her they were. She transferred me to the library, where an employee was also puzzled, but welcomed me to come in and take a look at their historical materials.

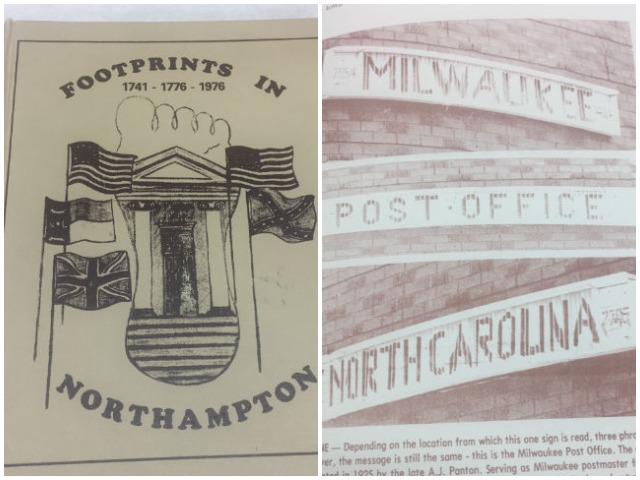

Having not yet gotten the hint from the locals that this was perhaps a waste of time and gas on what was already going to be a 400-mile drive, I eagerly drove to tiny Jackson (population: 513), the county seat, and parked at the Northampton Memorial Library. Inside, there were a couple of kids using computers and an adult perusing the shelves. A friendly librarian, accurately assuming I was the guy who’d called to research Milwaukee, laughingly told me I was the only person who’d ever inquired about such a thing. She brought me a 216-page book about the county’s history called "Footprints in Northampton: 1741-1776-1976," which was published in honor of its bicentennial and was apparently the definitive text on Northampton’s communities.

The entire section on Milwaukee was page 179, and it comprised a befitting amount of compelling information.

According to "Footprints," the town of Milwaukee was settled "around the year" 1889. Originally, it was known as Bethany, which is still the name of the Methodist church there. The land for the church was given by Billy Gilliam, and its first superintendent was James Thomas Carter Martin.

In 1885, when the Seaboard Airline Railroad – which operated from 1900 to 1967 in the Southeast – built a branch at the Roanoke and Tar River (Huckleberry Special), "Footprints" says, "the train slacked speed and threw out a mailbag near the residence of Cecil Askew." In 1902, A.J. Panton became postmaster and built a small post office convenient to his blacksmith’s shop.

In 1915, the town was incorporated and given the name Milwaukee by Hesikiah Lasker, a conductor on the S.A.L. Railroad. "Footprints," which makes a most un-southern effort to conserve words and details, says simply, "the town was named for the city in Wisconsin." So that settles that.

The only other information about Milwaukee in "Footprints" involves its post office sign, which contains the words "Milwaukee," "Post Office" and "North Carolina." The following is directly quoted from the book:

Depending on the location from which this sign is read, three phrases may be seen. However, the message is still the same – this is the Milwaukee Post Office. The original sign was constructed in 1925 by the late A.J. Panton. Serving as Milwaukee postmaster for 40 years, Panton, an immigrant from England, had seen a similar sign in St. Louis and returned to Northampton to build one. According to Mrs. Pearl Jenkins, Panton’s daughter, "post office" is written on the flat board and "Milwaukee" and "North Carolina" are written on the right and left sides of the vertical petitions. Panton’s son Charlie, area blacksmith, has made repairs on this sign which has hung above the Milwaukee post office door for almost 50 years.

Having learned almost nothing all there was to learn about my destination, I thanked the librarian and left. After driving a dozen highway miles east from Jackson on Dusty Hill Road, I finally came upon my first sign of Milwaukee: a sign for Milwaukee.

I soon reached the center of town, fittingly at the intersection of the two most rural North Carolina-sounding roads imaginable: Doolittle Mill and Buck Boone. East on Buck Boone, I passed the railroad – where ol’ Cecil Askew had that mailbag thrown at him from a passing S.A.L. train – and then Ralph C. Askew and Son’s abandoned seed peanut business.

The derelict or dilapidated building was a common sight in Milwaukee, which appeared to be quite down on its luck.

The median household income in Northampton County in 2015 was $30,429, almost half the national average of $57,230. The median age was 47.1 and the population has been declining for decades.

While Northampton County – as mentioned above – overwhelmingly votes blue, a couple of houses still had Trump-Pence signs outside and the town seemed to exemplify how rural, economically depressed districts went so hard for Donald Trump in 2016.

I passed the Public Ministry-Jesus Christ, which looked in bad shape. Another building, right on the corner of Doolittle Mill and Buck Boone, clearly had endured a bad fire and was condemned, with "Keep Out" painted in red on the door.

In the distance, a radio tower dwarfed a Northampton water tower, which was behind a spacious lot that held a well-appointed shed, playground, trampoline and basketball hoop, beside a broken-down car and a small, ramshackle house.

But elsewhere, there were signs of a bit more spirit. A few homes proudly displayed their Christmas lights and decorations, the Milwaukee Cemetery seemed well-maintained and Bethany United Methodist Church was in immaculate condition – though the neighboring Civic Center looked like it hadn’t hosted an event in a while.

I passed some cars, but didn’t see a single person outside. On my way out of town, I stopped at Sidney’s Market (est. 1948) and bought an energy drink, a bag of chips and, because the store advertised its "best homemade ice cream," an ice cream cone. I talked to the attendant about Milwaukee, and she described it as "quiet" and "slow-paced" and "people don’t really have a lot to do." She also said she liked it, and business was good – not totally surprising, given it’s the only shop in town.

Unfortunately, my ice cream, chalky and flavorless, tasted like it had been left out since William Jennings Bryan lost Northampton County, and I had to throw it out. But in the meantime, several cars pulled up and stopped at Sidney’s, and it was the closest thing to a community gathering I figured there’d be. So I went back inside to irritate some locals.

After calling an impromptu town hall with the half-dozen people at Sidney’s, some general consensuses emerged: no, they hadn’t really thought about the name Milwaukee before; yes, they figured it came from Milwaukee, Wisconsin, but no, they didn’t know much about the place except beer, the Green Bay Packers and, in one guy’s case, Jeffrey Dahmer; no, it hasn’t been the best of times in the area lately, for reasons nobody really wanted to explore; yes, it is weird that someone wants to write about this place.

I apologetically thanked everyone and left, got in my car, drank the energy drink and drove to Washington, D.C. On the way, I thought about how nobody – from the town’s founders to the county textbook authors to the Northampton staffer and librarian to the current residents to the internet – had really thought much about Milwaukee, North Carolina. And then I thought about how that kind of makes sense, having been there, but that I was glad I went anyway.

Born in Milwaukee but a product of Shorewood High School (go ‘Hounds!) and Northwestern University (go ‘Cats!), Jimmy never knew the schoolboy bliss of cheering for a winning football, basketball or baseball team. So he ditched being a fan in order to cover sports professionally - occasionally objectively, always passionately. He's lived in Chicago, New York and Dallas, but now resides again in his beloved Brew City and is an ardent attacker of the notorious Milwaukee Inferiority Complex.

After interning at print publications like Birds and Blooms (official motto: "America's #1 backyard birding and gardening magazine!"), Sports Illustrated (unofficial motto: "Subscribe and save up to 90% off the cover price!") and The Dallas Morning News (a newspaper!), Jimmy worked for web outlets like CBSSports.com, where he was a Packers beat reporter, and FOX Sports Wisconsin, where he managed digital content. He's a proponent and frequent user of em dashes, parenthetical asides, descriptive appositives and, really, anything that makes his sentences longer and more needlessly complex.

Jimmy appreciates references to late '90s Brewers and Bucks players and is the curator of the unofficial John Jaha Hall of Fame. He also enjoys running, biking and soccer, but isn't too annoying about them. He writes about sports - both mainstream and unconventional - and non-sports, including history, music, food, art and even golf (just kidding!), and welcomes reader suggestions for off-the-beaten-path story ideas.