At about 10 a.m. on the morning of Oct. 14, 1852, John M.W. Lace, 35, was one of several people looking at a display of photographs in the window of a bookstore on Wisconsin Avenue when Mary Ann Wheeler, 23, a seamstress, walked up behind him, drew a double-barreled pistol from under her shawl and shot him in the back of the head at point-blank range.

Several people saw the murder, including a nearby deputy sheriff named John Shortell, who said, "I saw a lady with a pistol in her hand, and I made a step forward and took it from her. She said she shot John Lace and was proud of it."

Investigators established Wheeler purchased the pistol six weeks earlier from a Milwaukee gun maker, returning to the shop the day before the murder to ask a clerk to load the weapon for her. That same day, she stopped at a different store to buy a folding knife, which she planned to use on Lace if the gun failed.

Yet jurors in two separate trials refused to convict her.

Wheeler was an unlikely killer. Originally from Ohio, she had moved to Milwaukee in 1849 and found work doing piecework sewing for hat and dressmakers. Soon after her arrival, she began a relationship with Lace, despite her landlady’s warning that Lace was no good. Matters between the two – in the prim words of the 1881 book "History of Milwaukee" – "progressed in time into relations not permissible in good society."

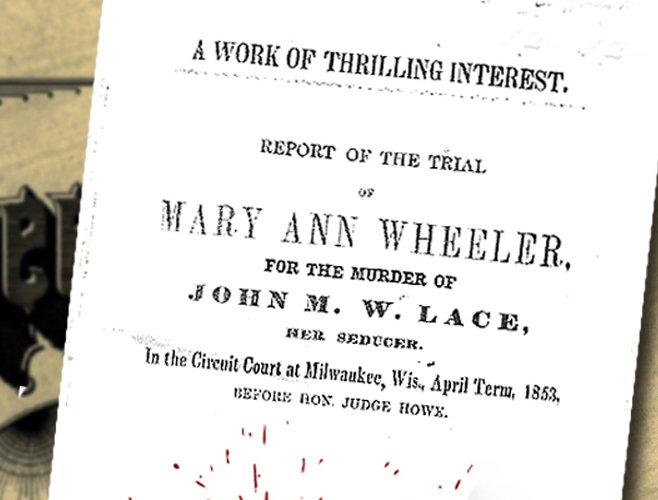

Mary Wheeler was brought to trial before the Milwaukee Circuit Court in May 1853. Witnesses described her as virtuous but very poor, living in a dingy basement apartment, frequently ill and working diligently each day from early in the morning until late at night to support herself. And she was pregnant with John Lace’s child.

She wrote several letters to Lace appealing to him to honor the commitments he had made to her, which had included talk of marriage.

Her attorney told jurors, "It will appear that her solicitations were disregarded; that he would not go see her; that she could not meet him in the street to talk with him, that he would avoid her, that seeing her ahead he would turn off; that she could seldom catch his eye, or if she did, he would look scornfully at her, or would make a pretext to stop and talk with someone … That finding herself thus pregnant, and thus neglected, she consulted a physician and resulted through his agency to instrumental means, to procure an abortion."

Witnesses testified Lace, instead of helping Mary Wheeler, delighted in reading her plaintive letters aloud in taverns around the city. Wheeler’s attorney argued this violation of her privacy, coupled with temporary insanity caused by the defendant’s fear of her "breach of moral rules," led to the shooting.

It was the first time a temporary insanity defense had been used in Wisconsin. District Attorney A.R. Butler, prosecuting the case, said she was both sane and cold-blooded. He noted she told investigators her only regret was not first touching Lace on the shoulder so that he would have known by whose hand he died.

The jury deliberated three days and nights but failed to agree on a verdict. A new trial was ordered. After a six-day trial, the second jury deliberated for 16 hours and, at 4 a.m., returned a verdict of not guilty by reason of temporary insanity.

Wheeler was immediately freed and, after a brief stay at the house of some friends, she moved back to Ohio. Her family – including her father, an uncle and a younger sister – had stood by her throughout the legal proceedings.

Press accounts from the time agreed: Lace was scoundrel, but Wheeler was clearly not insane. The Evening Wisconsin wrote, "Lace had not only rifled Miss Wheeler of her virtue, but he had the baseness to boast of it and show her letters. A man who will show a woman's letters, written in the confidence of love, deserves to be gridironed. The jury knew all this, and they felt it, and they brought in a verdict of not guilty, even when the letter of the law and the evidence would have pronounced her guilty."

The Milwaukee Sentinel editorialized, "The conduct of Lace toward the prisoner was wanton, cruel, unmanly, base in the extreme. But all this constituted no justification in the eye of the law for taking his life. It would not and did not justify the verdict of the jury."

But jurors looked at Mary Ann Wheeler, described in the Milwaukee Sentinel as "calm and self-possessed" in court but with "an air of subdued sadness," and, perhaps, felt justice had already been served.