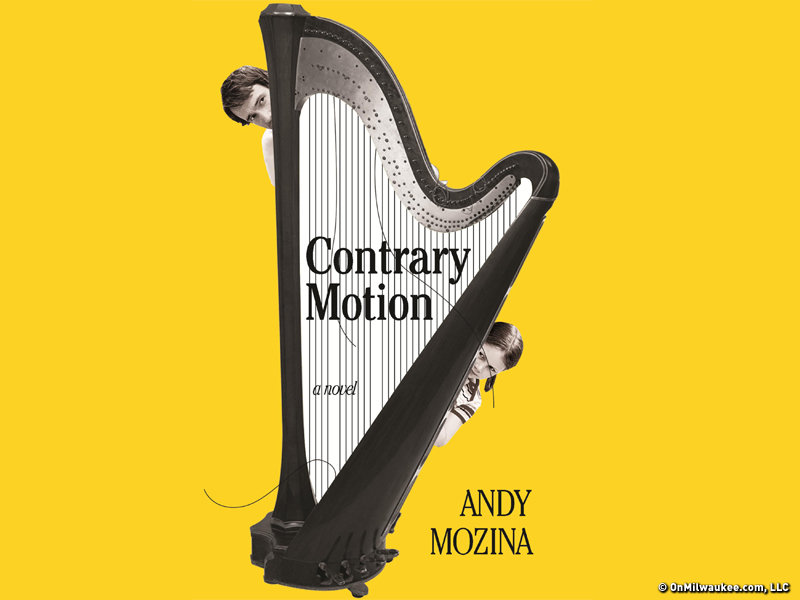

Milwaukee boy Andy Mozina return home to read from his latest novel, "Contrary Motion," on Wednesday, March 30 at 7 p.m. at Boswell Book Co., 2559 N. Downer Ave.

To give you a taste of Mozina's funny and insightful debut novel, we offer this excerpt from it...

I’m a Midwesterner, born and raised in Milwaukee, where they manufacture beer and the heavy machinery you should not operate while drinking it. The youngest son of a civil engineer and a nurse, with four brothers and two sisters, I was a large but inert child in a subdivision crawling with three-sport athletes, Eagle Scouts, and kick-the-can prodigies. I grew to be six feet one, cube-headed, block-shouldered, an average white male with no vowels in my last name, and I fell in love with the harp, of all things. I chose a musician’s life, which has proved difficult because at every moment – and for reasons I’m still trying to understand – I go about my business with a deep-seated sense that I am about to fail. This has undermined me both as a harpist and as a person, not to mention as an Ameri-

can.

Nevertheless, for twenty-five years now, I’ve dedicated myself to winning a principal harp chair in a top-drawer orchestra. I moved to Chicago, got educated, degreed, and married, had a daughter – Audrey – and finally, sixteen months ago, drove my wife, Milena, into divorcing me. Shortly thereafter, the truck that carried me away from my family and our drafty but close-

to-the-lake apartment ejected me to the curb on Rockwell Street in Humboldt Park, where rents are low, car windows are occasionally smashed, and, in warm weather, young men hang out on the stoops with live snakes wrapped around their shoulders.

After regrouping for a year, I met a smart and attractive woman and, against all odds, managed to build a relationship with her that is approaching the crucial four-month mark. Cynthia is a lawyer, short and feisty, very like a gymnast, with a fantastic crinkly-eyed smile and somewhat anxious ways. To be honest, I haven’t totally hit my stride with her – maybe because I want to please her so badly – but things definitely have the potential to get serious. In fifty-seven days, I have an audition with the St. Louis Symphony. Since my maniacal practice habits were part of my downfall with Milena, I’m on my guard against making the same mistakes. Luckily, Cynthia is somewhat of a work fiend herself and no stranger to crazy, high-pressure dead-

lines.

Topping all this, with the suddenness of an earthquake that has me feeling around for familiar objects in its aftermath, my father died three days ago. Because he had been battling a stubborn prostate cancer for about eight months, his heart attack has come as a surprise.

In the days since, his death has shifted appearances, making everything sadder, but also clearer, starker. In a sort of post-traumatic stress response to the many harp auditions I’ve endured over the years, I see even the smallest challenge as a make-or-break audition – from parallel parking to opening the plastic liner in a box of Cheerios without tearing a horrific gash. But this perception has never felt as all-encompassing as it does now. I get the sense that I’m auditioning not only for St. Louis, but for an entirely new life.

It’s the first Wednesday of April, overcast, with the temperature struggling to do a chin-up on the fifty-degree bar. Picking up Audrey to take her to my father’s wake, I get buzzed into Near North Montessori and head to the six-to-nine-year-old classroom, where the after-school program has just begun. I spy Audrey potting a tiny plant on a low table. She’s got Milena’s pale green eyes and straight black hair – cut short because she prefers tomboy to girlie-girl right now – but her nose and mouth echo my own. Milena and I will always be together in our daughter’s face, which is comforting and also at times pretty much unbearable. AsI approach, I see she’s spilled a fair amount of loamy dirt on the table, on the small chair she stands in front of, and on the carpet.

"Stay up, you stupid plant!" she says. She presses down too hard near the base of the stem, tilting the plant toward her.

"Hey, sweetie," I say. I feel an aching desire to fold her into myself, to let her step into me, like a violin slipped into its case, to what purpose I do not know.

"This plant won’t stay up."

"It’s all right," I say.

She growls and pushes the orange plastic pot away from her. The stem leans over a landscape of her violent fingerprints in soil.

Aggravation sets in as I try to clean up before one of the overworked teachers gets involved: finding the broom and dustpan for the dirt Audrey spilled, dampening paper towels for the finer residue, leaving black smudges on the carpet because damp paper towels were a very bad idea, ruing the curious location of this gardening operation, getting a headrush from stooping and standing, directing Audrey’s clumsy movements, encouraging her so she doesn’t melt down. I can’t help thinking about my own father’s impatience, which I see in myself, and which I’m desperately trying to escape one instant at a time.

I sign Audrey out, then we go to her locker, which contains her coat, splotchy homeward-bound artwork on crinkled paper, a clay bug with a painted body and pipe-cleaner legs – I can tell that one of its plastic bubble eyes will not adhere for long – and the stuffed unicorn she calls her "guy." There are also two black dresses on a hanger zipped into a see-through dress bag and a backpack full of clothes, courtesy of Milena.

Milena got along surprisingly well with my father, and she had sounded genuinely sad to hear about his passing. "You take care," she said earnestly when our brief conversation ended.

Milena’s lack of spirituality coupled with her deep belief in shopping and dance clubs had initially made my parents wary of her. I remember being especially nervous at our rehearsal dinner. It took place at a Nob Hill restaurant in San Francisco, in a private room with sea creature murals. I was afraid my mother might slip Milena a pamphlet on the rhythm method while my father insisted on sending her the household budgeting software he’d written. It was also the first time our parents met each other, and Milena’s parents were alarmingly smooth and chic. Shortly after introductions, via a segue known only to him, my father launched into a careful explanation of how the suspension cables transmitted forces on the Golden Gate Bridge. Then he excused himself to get a beer. Near the end of cocktails, Milena found him sitting alone and pulled up a chair. It wasn’t long before she had him laughing and smiling his big smile, the one that showed the gold caps on his back teeth.

After we collect Audrey’s things, she is quiet, pensive. We’re in the hall, heading for the door, so I risk it:

"Sweetie, are you thinking about Grandpa?"

She shakes her head no.

I have no idea how to talk to a six-year-old about death. At least she has almost no sense of what’s proper, so no matter what idiotic things I might say – "Grandpa’s spirit is in every can of soda we drink!" or "We’re all very angry at God for making it so we die" – my child probably won’t think less of me.

Excerpted from CONTRARY MOTION by Andy Mozina. Copyright © 2016 by Andy Mozina. Excerpted by permission of Spiegel & Grau, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.