Editor’s note: This is the second in a two-part series about sexual harassment in Milwaukee. Part one focused on black women’s experiences.

As the #MeToo movement continues to gain momentum, women in hourly wage, blue collar jobs are grappling with how to address sexual harassment in their work places. For them, the stakes of reporting harassment are high.

"You endure it because you have to," explained Amber Tucker, manager of youth programs at the MKE LGBT Community Center and adjunct sociology professor at Cardinal Stritch University.

"The decision to report harassment comes down to a paycheck. For women working for hourly wages, the lack of benefits, health insurance, and perhaps the educational qualifications to get another job all contribute to a feeling of powerlessness and insecurity," Tucker said.

One African-American woman, who asked not to be identified, was working on Milwaukee’s North Side as a cashier for a retail company. For about two years, her male supervisor targeted her, making inappropriate, overtly sexual comments, inviting her on dates, leaning over her and rubbing his body against her.

She felt uncomfortable, but she said nothing to him or anyone else. As a single mother of four young kids at the time, she did not want to risk losing her job.

"I didn’t want to make a big thing or big commotion and have it end up with me being fired or people looking at me differently," she said. "I just tried to stay as distant as possible and continue working there, just hoping that all that stuff would die down. But it made me feel bad, like, we have to go through this just to be able to work?"

Eventually, the harassment by her supervisor did stop, and Renee (not her real name) held that job for about 15 years while raising her four children.

"Now if it happened to me I would react differently because my kids are old, but back then I couldn’t lose my job," said Renee, now 43.

Many women in low-wage jobs face a similar predicament. According to Tucker, the fear of retaliation "may override the ability or the capacity to report to an authority, especially if (the harasser) is in a position of power." She added, "Really it’s about power, and so when you add in class, that’s another level of subordination."

In Renee’s case and for others like her, Tucker said the choice to stay in their jobs can also be a way to assert their own power.

"Sometimes asserting that power is just not leaving and not quitting," Tucker said. "You’re doing this to me, but I’m going to show you that you’re not going to win."

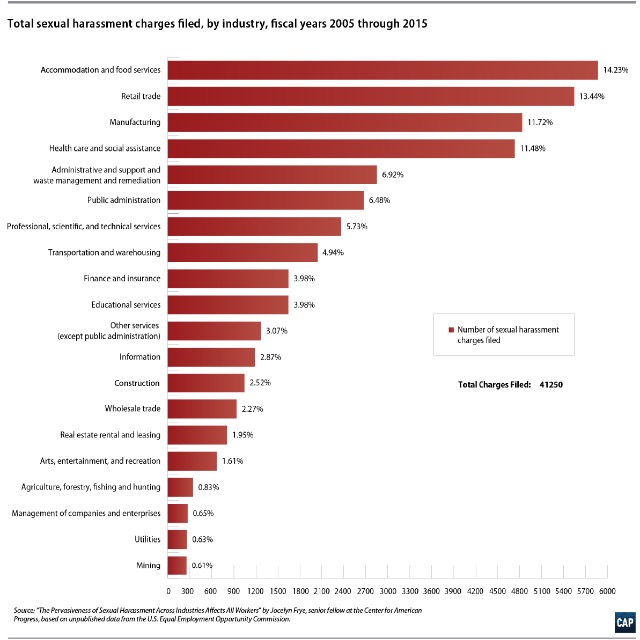

A study by the Center for American Progress showed that between 2005 and 2015 female- dominated industries accounted for significant percentages of workplace sexual harassment charges filed with the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Fourteen percent of the charges were in the accommodation and food services (defined as providing customers with lodging and/or preparing meals, snacks and beverages for immediate consumption); 13 percent in retail trade; and 11 percent in the health care and social assistance.

Accommodation and food service workers make up 7 percent of the total U.S. workforce, and more than half of the employees are female. Health care and social assistance workers make up 13.5 percent of the nation’s workforce and nearly 80 percent are women.

(Click here for larger image.)

(Click here for larger image.)

At her job as a caregiver at a small group home, Ashley (not her real name) had a co-worker who often made inappropriate comments to her. Ashley was in her early 30s and a single mother; the co-worker was a driver for the company and a friend of the owner. He always found excuses to come when she was on the shift, she said.

"I noticed that every time he would come around he would give me strange looks, and so I kind of felt it coming," Ashley said. "I thought that maybe if I would show him that I’m not too interested, maybe if I … keep it moving and give him no eye contact or anything like that he wouldn’t try to pursue it," she said.

She largely ignored his comments, acting standoffish in the hopes that he would leave her alone, until one day, just a few months into her job, he grabbed her.

"It was a Saturday morning, I remember," she said. He touched her breast while passing her on the back stairs of the client’s home.

"You never know what you would do in those types of situations, and I literally, I didn’t react. I kind of — and I hate that I did this now — but I just kept going, I just kept coming down the stairs and I just brushed it off."

Ashley, who is African-American, did not tell anyone about the incident, but before the end of the week, she quit. She felt overwhelmed, she said. Not only did this physical invasion of privacy make her feel vulnerable and taken advantage of, but she was also anxious about what else he might do to her and nervous to tell anyone about it.

"If you go tell your story to someone, you have to worry about the judgment from them, and then you have to worry about them saying, ‘Why didn’t you do this?’ or, ‘Why didn’t you react this way?’ and you don’t want to go through that," Ashley said.

Even today, Ashley, now 40 and a community organizer living in the Uptown neighborhood, often looks back on that incident of sexual harassment and wonders what might have happened had she reported the abuse. Would she have been fired? Or, could she have grown her career with that company?

"I was a new employee, I was younger, and I’m wiser now, and I think now I probably would have told her (the owner) because I’m more familiar about laws and policies," Ashley said.

Both Ashley and Renee agreed that many companies could improve their sexual harassment policies. Neither of them received formal training at these jobs. Employers prioritized and reiterated scheduling rules and vacation day policies at orientations but failed to inform workers about sexual harassment policies and what to do if they are harassed, Ashley said.

Astar Herndon, the state director of 9to5 Wisconsin, said most workplaces – especially those with low-wage workers – do not provide any information about sexual harassment, except for maybe in a manual or pamphlet. Thanks to the popularity of the #MeToo movement, 9to5 Wisconsin, which is part of a national advocacy organization that protects the rights of working women, is ramping up its anti-sexual harassment efforts. It is reaching out to local businesses to offer free workplace training to employees. 9to5 aims to help women know their rights and equip them to feel empowered in the workplace, Herndon said.

"We’re grateful for the high profile stars that have come out and brought awareness to this," Herndon said. "Women living at the margins are feeling it in a more pointed way, and it’s far more oppressive."

She added that 9to5 has seen an upswing in businesses and workers reaching out to the organization for resources during the past few months. The Wisconsin chapter is restructuring its website and updating materials to make resources about workers’ rights more accessible and relevant.

Herndon said she’s glad to see a culture shift occurring, but noted that there is much progress left to be made. In many industries, the work of women is inherently devalued, she said. Restaurant industry workers, for example, depend on tipping, which inherently emphasizes physical appearance, she said.

A 2014 study on sexual harassment in the service industry reported that women comprise two-thirds of all tipped restaurant workers.

Respondents reported experiencing sexual harassment from managers, co-workers and customers. More than half of the women surveyed said they experienced sexual harassment on at least a weekly basis, including deliberate touching and sexual teasing, jokes, remarks or questions from customers.

Kristina Nailen, 31, who has worked at five Milwaukee bars and restaurants, said harassment from customers is an unspoken aspect of the industry.

"It’s what’s expected. It’s part of the job. It’s difficult to go and tattle on a customer," said Nailen, who is white. "That’s the way it feels as a woman on the job. You don’t necessarily feel very empowered."

Her first job in the service industry was at a bar on the South Side, near her home in the Historic Mitchell Street neighborhood. She said she was immediately surprised by – and extremely uncomfortable – with the overt flirting and inappropriate comments from customers.

Around the same time, Nailen was working one of her first shifts at a sports bar in West Allis when a customer grabbed her backside as she walked by his table.

"It shook me," she said. "I gave him a sideways look, and then I hustled back behind the bar where it was safe." She told no one about the incident and went on with her work as normal.

"There’s people all around. They see it, they hear it, but nothing ever gets done about it," Nailen said. "If I were my true self about it, I would prefer that they (harassers) be kicked out … but we’re not in a position as servers to do that."

Today, Nailen works four jobs, two of which are in the service industry, to pay for student loans, rent, car payment and other basic needs.

"I do this because it’s important to me to be independent and meet some other financial goals, and that’s been really difficult to do without the supplemental income that I find in the service industry."

She said sexual harassment by customers is rarely a topic of conversation among co-workers, and she has not yet seen the effects of the #MeToo movement reach the service industry.

"I think that in real time what we’re still seeing is the same," she said. "I have not had any discussions with my female co-workers about these issues or the movement. I don’t hear it talked about on the job at all."

Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service partnered with Milwaukee PBS to cover the issue of sexual harassment in Milwaukee. View the program here: milwaukeepbs.org/local-programs/programs/10thirtysix.