By 1969, the tired old building at Water and St. Paul looked like just another Downtown dive awaiting the wrecking ball. The Cross Keys Hotel, 400 N. Water St., long surrounded by warehouses "one sneeze from falling in the river," had become the last building standing on what had once been a dense city block.

What most people didn’t realize was that the Cross Keys was the oldest building on the oldest street in the city – and probably one of the oldest buildings in the state. Before being ravaged by fire and razed for parking, the Cross Keys had a long and colorful life, filled with disaster, violence and scandal.

(PHOTO: Milwaukee County Historical Society)

(PHOTO: Milwaukee County Historical Society)

Bailey Stimson, a "mutton chops Englishman" from Cambridgeshire, established the Cross Keys Hotel in early 1843. The two-story wooden frame house quickly became a local favorite for visiting Englishmen. Everything about the Cross Keys was English, featuring heirloom silver pots of tea, plum pudding, racks of beef, Cornish hens and homemade divinity. Meatpacking pioneers Frederick and John Layton lived here when they arrived in Milwaukee in 1845.

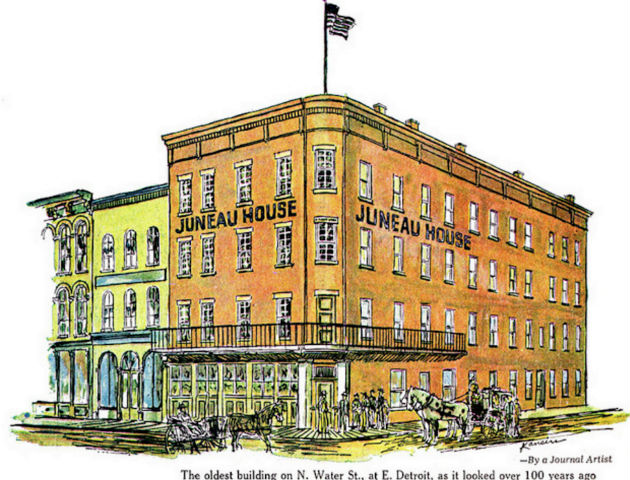

The tiny English inn was replaced with a modern four-story building in 1853. Although built of Cream City brick, the Cross Keys was painted in bold reds because Stimson found the Cream City color "sickly." Iron work was just coming into vogue, so the building was decorated with a wrought-iron balcony and iron balustrades fashioned by the Reliance Iron Works. During construction, a limestone plate was erected above the main entrance, reading "B. Stimson July 4, 1853."

On Dec. 16, 1853, the hotel’s grand opening was celebrated with an old-fashioned housewarming party, including punch with raisins, baked apples with maple syrup and hot corn bread with buttermilk. It was boom times in Milwaukee: Mayor George Walker was expanding the city in every direction, gas pipes were being laid, wooden buildings were being replaced by fireproof brick and the population had just cracked 25,000. Out went Solomon Juneau’s log shanty, in came modern accommodations.

The Milwaukee River froze over on Dec. 19, 1853 and was closed to navigation. However, hot and cold water still ran from the pipes of the Cross Keys at the twist of a faucet. Before most Milwaukee homes and businesses were outfitted with city water, the Cross Keys installed wooden conduits piping water from a spring at the lakeshore. The hotel never failed to deliver on its promise of "running water at all times."

On Sept. 30, 1859, an American president put the hotel’s hospitality to the test. Abraham Lincoln visited the Wisconsin Agricultural Society convention, held at 12th and Wells in the old Red Arrow Park. Although he stayed at the most fashionable Newhall House hotel three blocks away, Lincoln came to the Cross Keys for breakfast, gave a speech from the iron balcony, and then took a "long and leisurely" bath in a Cross Keys tub. Apparently, the Newhall House didn’t have tubs large enough to suit the 6'4" president.

For decades, antique vendors sought to locate Lincoln’s bathtub, but it was never found. After the hotel closed in 1879, the tub was used as a coal bin for decades and eventually discarded.

(PHOTO: Historic Photo Collection, Milwaukee Public Library)

(PHOTO: Historic Photo Collection, Milwaukee Public Library)

The building was forever known as the Cross Keys Hotel, even though it operated by that name for less than 20 years. Afterwards, it was known as Stimson’s Hotel (1861), Juneau House (1863), Russell House (1867), American House (1869) and European Hotel (1875).

In the 1840s, the area was filled with traveler’s hotels supporting the Huron (Clybourn) and Detroit (St. Paul) sea passenger docks. When the railroads came to Milwaukee, the hotels moved to where the depots were (first, 2nd and Seeboth, then East Wisconsin Avenue, and then Fourth and Michigan.) By 1879, the old Cross Keys Hotel closed its hotel operation forever, and the ground floor was renovated as commercial storefronts.

The hotel was fortunate enough to survive both an 1865 fire and the Great Third Ward Fire of 1892, but a vicious fourth floor fire in 1923 destroyed its original Italianate features and required the removal of the building’s top floor. The Cross Keys went from heavily decorated to sparsely streamlined almost overnight.

By 1954, the Milwaukee Journal described the Cross Keys as "simply an old building that has long lost its name and purpose." Over 100 years’ time, Water Street had been raised three times and the old building continued to settle into the unstable marshland it had been built upon. The lobby of the old hotel had been above street level on opening day. By 1954, the same space, now a barbershop, was more than five feet below the street.

(PHOTO: Historic Photo Collection, Milwaukee Public Library)

(PHOTO: Historic Photo Collection, Milwaukee Public Library)

By the 1960s, gay bars began migrating to the down-low storefronts of Downtown’s south end. The 400 N. Plankinton block, with the Fox Bar (1948,) Tony’s Riviera (1952) and Mary’s Old Mill (1959,) became the city’s first gay nightlife strip. Just across the river, the popular Crystal Palace (1964-69) kept the lights on at the Cross Keys – and probably saved it from demolition.

In 1969, architectural historian H. Russell Zimmerman expressed doubt that the Cross Keys would survive the expressway era. It was known to be the oldest surviving commercial building in the city, but never really recognized for having any cultural or architectural value.

Eventually, the 400 N. Plankinton block was razed, and gay nightlife moved south to 2nd and Pittsburgh. Al Barry, proprietor of the Rooster Bar (181 S. 2nd St., now Just Art’s Saloon) brought a new concept to the Cross Keys in 1969. The River Queen quickly became the breakout hit of its time. At a time when many gay bars were still little more than bust-outs, the River Queen was straight up opulent. With a Storyville bordello theme, the bar was decked out in red velvet everything, smoked mirrors, live floral arrangements and a massive crystal chandelier.

The River Queen became famous for celebrity sightings: Liberace, Milton Berle, Paul Lynde, Carol Channing and others could be seen here after local theater performances. It was a place to see and be seen.

(PHOTO: Wisconsin LGBT History Project)

(PHOTO: Wisconsin LGBT History Project)

After the Wreck Room opened in 1972 and the Factory opened in 1973, the River Queen became part of a new Third Ward nightlife circuit affectionately called "the Fruit Loop" that later included the Club Health Spa (1974) and the M&M Club (1976).

Independent of syndicate protection, the River Queen was forever being slapped with amplified charges of disorderly conduct, serving after hours, underage loitering, prostitution and fire code violations. Its liquor license was in jeopardy throughout most of its existence. Overwhelmed by this nonsense, Al Barry eventually sold the booming business to focus on his less complicated nightlife properties.

In January 1976, the River Queen became the scene of a massive police corruption scandal. To avoid police harassment, the new owner had given cash bribes in excess of $1,000, expensive gifts (including 25 electric razors), cases of liquor and daily free drinks to more than 50 police offers and their wives between 1973 and 1974.

An intense investigation ensued, and the findings were bizarre. After hearing how a drunken officer showed off his new gun by firing bullets into the bar’s ceilings, detectives removed wood paneling and found two bullets wedged in the walls. One officer reported seeing a colleague staggering drunk down Wisconsin Avenue at 6:30 a.m. after having 8-10 after-hours drinks at the bar. One source claimed that officers would stay in the bar until 7 a.m. while being serviced by prostitutes. The River Queen was now a house of ill repute.

Investigators traveled to Minneapolis and Chicago to obtain shadowy testimonials from former bartenders and patrons. "Detectives say that homosexuals, like prostitutes, are often valuable sources of information about criminal activity," reported the Milwaukee Journal.

Although the investigation did not result in any charges, due to a lack of hard evidence, the controversy caused the end of the River Queen. When the bar closed in summer 1976, its patrons took every souvenir they could get, and some people still own barstools to this day.

The August 1976 issue of the local GLIB Guide offers a farewell to the River Queen, stating: "… the River Queen has closed, remodeled and reopened as the Side Door. The new bar is an expanded version of the old bar, with plush carpeting and a giant-size TV screen. The Side Door also features a disco." The Side Door used the side entrance door’s address of 212 E. St. Paul Ave.

In early 1977, a new owner tried to overcome the scandal by opening a "sophisticated" jazz club. Due to continued licensing problems, Sharon’s didn’t last long. It didn’t help that the property owner was charging $1,000 per month in rent ($3,977 in 2016 dollars). The S.S. River Queen tried a relaunch in 1978, but it just didn’t float. Jocks opened and closed here within the next year, and by fall 1979, the building’s only occupant was the Waterfront Cafe.

On Wednesday, November 28, 1979, a three-alarm fire broke out at the Cross Keys at 4:15 a.m. The fire started on the first floor and was fought by more than 100 firefighters. Somehow, the State Fire Marshal never found its cause. The dollar loss was cited as only $200,000, but the cultural loss was far, far greater.

After 127 years at the corner of St. Paul and Water, the Cross Keys was razed in May 1980 for a parking lot. The land stayed vacant for 25 years. In 2005, the Milwaukee Public Market opened on the exact footprint of the old Cross Keys Hotel.

(PHOTO: Milwaukee County Historical Society/Wisconsin LGBT History Project)

(PHOTO: Milwaukee County Historical Society/Wisconsin LGBT History Project)

The Wisconsin LGBT History Project welcomes any additional information about the Crystal Palace or the River Queen. Do you have stories, photos or memorabilia to share? Please contact us at info@milwaukeepride.org.

Explore hidden history! LGBT Milwaukee, a new book from Arcadia Publishing, is the first comprehensive social history of local LGBTQ lives from the 1930s to today. Your purchase directly benefits Milwaukee Pride’s ongoing efforts to document, preserve and celebrate local LGBTQ history.