Harry Erlach was a captain with the Milwaukee Police Department whose specialty was estimating the size of crowds at public events in the city. For more than 20 years he'd sized up some huge mobs, including the 125,000 people who invaded the city for the opening of the Milwaukee Mid-Summer Festival – a forerunner of Summerfest – on July 13, 1940.

That turned out to be just a warm-up for the supreme test of Erlach's skill that came one year later – 71 years ago tomorrow – when the Fraternal Order of Eagles and the Pabst Brewing Co. staged a prizefight at the lakefront. By Erlach's reckoning there were 135,000 people there to see it – still the largest crowd to ever attend a sporting event in Wisconsin and a boxing match anywhere.

The scheduled 10-round fight was the centerpiece of the international convention of the FOE held in town that week. Founded in Seattle in 1898, the FOE was an organization like the Elks and Moose that raised money for charity and promoted a civic agenda set each year at the organization's convention attended by Eagles from all over the USA and Canada.

Twice before the FOE convention was held in Milwaukee, and both times the chief diversion arranged for delegates was a boxing match. The first one was on Aug. 17, 1906 at the Pavilion in Schlitz Park on North 8th and West Walnut Streets, where local lightweight Charley Neary knocked out the famously dissolute Aurelio Herrera in the seventh round.

Herrera's robe was festooned with convention badges that apparently he got while partying with delegates right up to fight time. "... Many are saying that the Mexican was pickled when he entered the ring," reported The Milwaukee Journal, "and that he was too drunk to know what he was doing."

A snort or two for Pinkey Mitchell and welterweight champ Joe Dundee before their Aug. 11, 1928 convention match at Borchert Field might've released their inhibitions and kept them from getting tossed out of the ring after six soporific rounds. The fight was declared No-Contest.

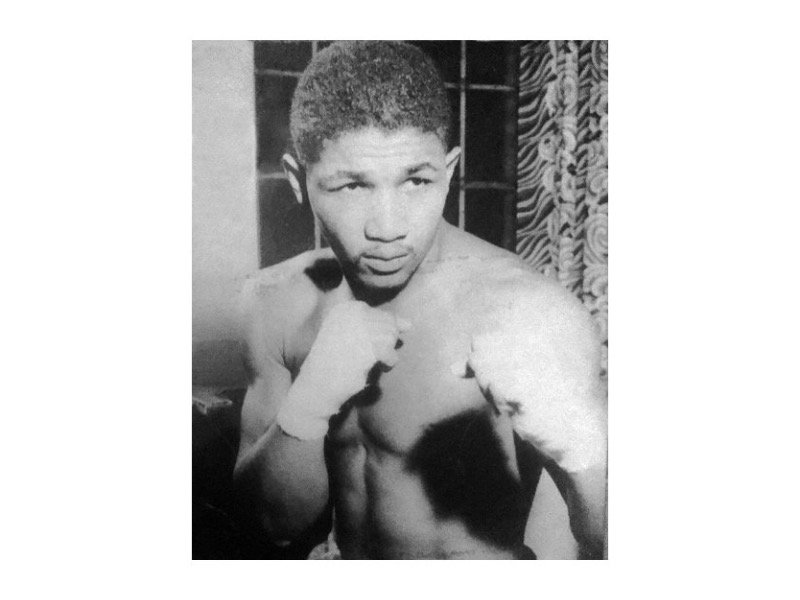

The Eagles and Pabst picked a surefire crowd-pleaser to headline their Aug. 16, 1941 fight at the lakefront. Known as the "Man of Steel" for his toughness in the ring and his background in the steel mills of his native Gary, Ind., Tony Zale was in the midst of a career that would land him in the Boxing Hall of Fame.

But the record crowd that turned out for his lakefront bash with Billy Pryor, the 160-pound champion of Texas and Colorado, wasn't lured by Zale's magnetism alone. They came because it didn't cost them a cent. The boxing card headlined by the middleweight champion of the world was absolutely free to the public.

Capt. Erlach wasn't the only one stunned by the attendance on that starlit night. When former heavyweight champ Jack Dempsey climbed through the ropes to referee the main event, he squinted out over the acres of humanity spread out around him and recollected a similar scene from 14 years earlier.

"This reminds me of the night I fought Gene Tunney in Chicago," said Dempsey, referring to the night in 1927 when the famous "Battle of the Long Count" was fought 90 miles to the south. The crowd at Soldier Field that night numbered 104,943.

About 45,000 Eagles attended the '41 convention. At the Pfister Hotel two dining rooms were closed so that cots could be put up for out-of-towners. In addition to the fight there was an "Eagles Day" at Borchert Field, home of the minor-league Milwaukee Brewers, and Fr. E.J. Flanagan, founder of Boys Town, celebrated an outdoor mass at Washington Park.

It was anticipated that the Zale-Pryor fight would draw up to 50,000 fans. That estimate was tossed out early Saturday afternoon when the first clumps of spectators began showing up for the event that would not begin for another seven hours. By 5 p.m., people were descending on the lakefront in such droves that the call went out for police reinforcements and Capt. Erlach began to warm up with a series of vigorous mental calisthenics.

"From every section of Milwaukee and from every suburb, people converged on the park," wrote Sports Illustrated's Harold Rosenthal in 1964. "Local police officials had never seen anything like it. They were afraid so huge a crowd might get out of hand. It flowed like heavy syrup around the raised ringside area, spread out for a quarter of a mile in the natural amphitheater, oozed up the hill to the drive where the buses arrived and filled every inch of the bluff overlooking the scene."

The people on the Juneau Park bluff brought binoculars and other implements to make sense out of the ant-like activity under the far-away ring lights. They could've stayed home and listened to a live broadcast of the fight over WTMJ Radio.

Fears of mass disorder were unfounded. "With so many strangers to the city in the crowd, it might have been expected that the 132 policemen assigned to keep things moving would have had their hands full," said the Journal the next day. "As it turned out, however, only one child was reported lost. He was recovered in a jiffy."

It was not so peaceable elsewhere in town that night. About two miles away, at what was probably the only other event held in Milwaukee then, the local chapter of the Communist Party held an outdoor rally that broke up when a spectator who dissented from the party line got punched in the eye. As the victim was put in an ambulance, it was reported, "he proudly pointed to his red badge of courage and said, 'See that – that proves I'm a good American!'"

If a black eye was proof of a fellow's patriotism, Billy Pryor was a star-spangled Yankee Doodle Dandy. Zale punched him to the canvas nine times and knocked him cold in the ninth round.

The last FOE convention boxing show co-sponsored by the Eagles and Pabst was on July 28, 1955. Held at Marquette Stadium in the Menomonee Valley, in the main event lightweight contender Kenny Lane stopped Elmer Lakatos in eight rounds, with Jack Dempsey again the referee. Admission was again free, but if Capt. Erlach was still crunching the numbers he hardly broke a sweat this time. The stadium was set up for a crowd of 50,000, but only 20,000 showed up.