The opinions expressed in this piece do not necessarily reflect the opinions of OnMilwaukee.com, its advertisers or editorial staff.

I bet you think I’m going to argue that the national war on police (well, at least as far as the narrative goes) is costing police lives. It’s cost some, as witnessed by recent horrific executions of cops in Texas and New York, where officers seemed to be targeted for no reason other than their badges. And clearly any death is too many and a direct attack against the rule of law.

However, I’m not talking about police deaths as a pattern because those are down under the Obama administration (the highest spike was in 1930 actually). Furthermore, firearm-related police deaths are down over last year at this time. Sounds counter-intuitive, but it also fits perfectly into what I am about to argue.

Instead, I’m posing this question: Whether it’s plausible to argue that at least one reason for the sudden national spikes in non-police related homicides in various American cities over the past year might be the result of the rhetorical (and in scattered cases, literal) "war on police."

What I mean is this: The downward crime trends in many American cities have been credited at least in part to the Broken Windows style of policing (pioneered in part by Milwaukee native George Kelling), which holds that intervention to stem even small signs of neighborhood disorder will prevent larger crimes from occurring because, well, the criminal element will see that someone cares, and the community won’t tolerate it.

Although it can be defined as intervention without ticket writing, it’s a more aggressive (or just proactive) style of policing that gets cops out of squad cars and away from chasing 911 calls and gets them to interact with the citizenry. This was tried with great fanfare by Bratton and Giuliani in New York, starting with subway fare beaters.

Allow one broken window to go untended, and more broken windows will crop up as social order frays more, and criminals get the message that anything goes, leading to more major crimes, the theory holds. And while many other variables might have played a role in crime drops since the early 1990s in American cities (things like birth cohorts), this is credited with having made a difference.

In Milwaukee, Arthur Jones was the first to embrace the Broken Windows theory, with his own variations (he tended to define it as ticket writing more than just intervention) and crime started to decrease (although he never got much credit for that). I remember that he used to have the Broken Windows book on his office shelf. People sometimes forget that homicide hit the 160s in the early 1990s and dropped to about half that. The recent trend is pulling back to those early 1990s numbers.

Now you’ve got homicides suddenly skyrocketing in American cities that have seen some of the most hardcore protest movements and critical incidents involving cops that received some of the most extensive media coverage (Milwaukee, St. Louis, and Baltimore). In two of those cities – St. Louis (well, it’s not really Ferguson, but close) and Baltimore – either they or a neighboring community were literally burned. In Baltimore, cops don’t trust an activist DA, either.

What happens when it’s not just a single window that’s broken on a block, but a city that is burning and on television no less? In other cities, all cops absorb the national message played over and over again on cable TV – there but the grace of God go I.

Maybe it’s the reverse Broken Windows effect, then, in practice if not policy; perhaps you end up with a scenario in which some average cops back off, even if ever so slightly. If you’re afraid of being the next Darren Wilson, you might give that field interview a pass or not stop as many cars. You might intervene just a bit less because, in the back of your mind, you’re worried about the national narrative. It’s a thought.

In a few cases, thinking twice might be a good thing (rotten cops exist just like rotten people exist in every profession, and they need to be rooted out; Broken Windows policing is not without criticism).

But even a slight backing off in field interviews, in traffic stops and the like, might make a real difference in establishing to the criminal element who’s in control. It’s an altering of the power dynamic between rule enforcers and rule breakers, however subtly; it’s about who has control of the turf. Disrespect for law enforcers is essentially disrespect for the rule of law – holding it illegitimate – and that could lead to more disrespect for life and all of society’s codes.

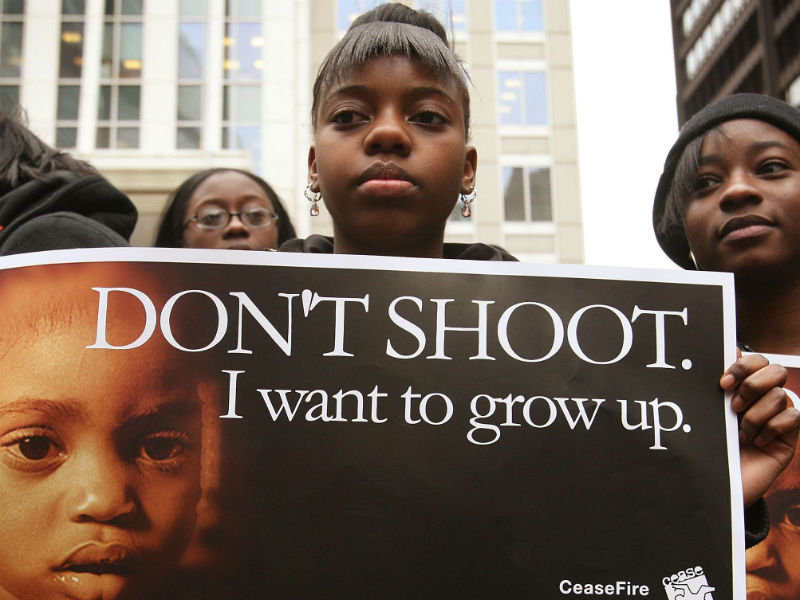

Ironically – and tragically – many of the victims of homicide are themselves black lives, of course. There’s a racial disparity when it comes to criminal victimization.

If cops are having fewer contacts with the citizenry in some of these cities, it would also hold that cop deaths might drop. In fact, some people believe that cop deaths dropped from the Bush to the Obama administrations in part because that trend just followed the general crime decrease trends in American society. Less violence means fewer cops encountering violent situations. Fewer police contacts with citizenry results in fewer cases in which cops have to defend themselves and sometimes can’t. And those gray area struggles or decisions for life or death are more common than cops being executed pointblank or citizens being criminally, unlawfully killed.

Here you have cop deaths still dropping (even fatal shootings of cops are down nationally this year to date compared to last year at this time) but homicide spiking in various cities.

Maybe it’s a tradeoff. Be careful what you wish for.

If the community is calling for less proactive policing, for less quality of life interventions, for fewer cops in their neighborhoods (like that coalition wants in Madison; they want the cops to stay away completely), for fewer traffic stops (because of racial profiling concerns continually raised) and so on, then maybe it’s a tradeoff.

American police are necessary for social control. When they let up, lawlessness can take root. Social control is necessary for organized society. Quality of life policing worked.

If a community doesn’t want the policing tactics that have worked over the past 25 years, then maybe an increase in crime is the cost of that, as lawbreakers become more emboldened and cops less visible.

The same is true, by the way, of recent trends toward diversion from sentencing and concerns about mass incarceration that have also taken root as narratives. If the pressure is to release more people who have committed crimes, then there might be a trade off from that too (acknowledging that at a certain point mass incarceration can also have a deleterious effect).

I don’t actually believe that any "community" wants the cops out, though; I think that a few protest movements have dominated the news coverage with sometimes incendiary rhetoric that is probably pretty far removed from the peaceful and positive interactions most cops have on a daily basis with most residents in the communities they serve. I think the media, by hyping and obsessing over disorder narratives, makes communities seem more dangerous than they are and people more anti-cop as a whole than they are. They cover crime the same way, frankly; you wouldn’t know that general national trends were toward declining crime until this year if you just watched the news.

So I think the degree to which people are "warring against police" is magnified and distorted by the media, especially national media; however, I also think that, if you are the average cop, that doesn’t matter because it embeds in your psyche anyway that you’re a target and could end up a headline.

I wouldn’t blame a single police officer in any American city for thinking twice and deciding writing that ticket or doing that field interview just might not be worth it.

Perhaps this comes at a cost.

That doesn’t mean that I think that all of the homicide spikes in American cities are the result of the protest movement or that no cop is doing his or her job and interacting with the community, as I don’t. I think homicide is an exceptionally complex issue that has multiple causes.

I do think the easy availability of firearms to the criminal element contributes. I think a general social peer pressure that rewards misbehavior and glorifies a criminal lifestyle is a factor. I think poverty is a factor. Perhaps the fact our society is getting younger is a factor. We should never fall into the trap of assuming that crime has a singular variable. It doesn’t. However, the things I cited above are static variables. What changed?

I also think that many if not most cops are still out there toiling away doing great jobs and interacting with neighborhoods in ways the media never report. I applaud them. I am speaking as a general trend or perception. Maybe the criminal element just perceives that American cops have backed off or are on the defense. That, alone, could embolden. Whose narrative prevails? Feeding perceptions of oppression and mistreatment can justify misbehavior in some people’s minds.

I’ve just never bought into the overriding narrative of the past year. That’s the bottom line. While some of the cop shootings have been deeply disturbing – the one of the man shot running away in South Carolina comes to mind – others have been gray area uses of lawful force, in which widely accepted narratives later proved false, such as the Michael Brown case. I am unwilling to lump all split second lawful uses of force into some national narrative of supposedly bad cops especially when use of force remains so statistically rare.

Criminal use of force is rarer still. American police are not the problem in American society, as a whole. Some of the cases, like Brown’s, involves situations in which officers were legally authorized to protect themselves. I don’t understand why cops have become the national enemy, as a profession, in a sweeping too-generalized faulty narrative driven by a few (even if some of those few are entirely warranted to have their grief).

Police didn’t cause poverty. They don’t cause crime. Or drop-out rates, etc. They don’t create jobs (although they create safer neighborhoods where jobs can come). They are better trained than ever before. They are subjected to multiple layers of review and oversight, far more than most any profession, even though they don’t get it right all the time. They go through extremely thorough hiring processes. They are imperfect (when E. Michael McCann didn’t charge a cop in an on-duty shooting for decades in Milwaukee, that caused mistrust). I get that. There’s a historical legacy of oppression dating back to Jim Crow that still resonates and is a very bad one. I get all of that too.

However, American police are necessary. They establish and maintain social order. We need them. Communities with high-crime need them most. Yet, cops can’t win. I can’t imagine the morale of the average cop these days. Their jobs were already hard enough. It wasn't that long ago, after 9/11, that cops were praised as society's heroes who, along with firefighters, ran into the Twin Towers and toward danger when others ran out. Now, in some corners, cops are trashed as society's anti-heroes who are criticized because they didn't run away from danger (as in, when people criticized Darren Wilson for not leaving the scene before the shooting).

I think the narrative and the rhetoric is too overreaching. And that might have a cost.

I think it’s at least plausible that the war on police has led to an in-practice retraction of more proactive policing of the sort that led to crime drops. What’s changed in the past year is the narrative. The national narrative, shaped by the media often in misleading fashion, is anti-cop. In city after city, we’ve seen cops (like Darren Wilson) pilloried and branded as racists and killers.

Although use of force remains an exceptionally rare event nationally (study after study has pegged it at just over one percent of all police contacts), the media have distorted the issue by hyping aberrations and making it seem more common than it really is, while overlooking the vast majority of police contacts that go well and the vast majority of cops who perform their jobs with excellence in the face of great pressure.

The anti-cop rhetoric has been too heated, too generalizing and too incendiary. The media can do its part by gravitating away from disorder narratives and episodic fragmented coverage of crime and toward contextual reporting.

To be clear, I’m talking about incidents like those in Minnesota where people called for cops to be fried like bacon, and I’m talking about incidents like those in Madison, where people called for killing cops while surrounding by all accounts a caring, community-oriented cop.

Has this come at a cost, ironically (and tragically) of, in part, black lives? Perhaps.

It’s worth considering anyway.

Jessica McBride spent a decade as an investigative, crime, and general assignment reporter for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel and is a former City Hall reporter/current columnist for the Waukesha Freeman.

She is the recipient of national and state journalism awards in topics that include short feature writing, investigative journalism, spot news reporting, magazine writing, blogging, web journalism, column writing, and background/interpretive reporting. McBride, a senior journalism lecturer at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, has taught journalism courses since 2000.

Her journalistic and opinion work has also appeared in broadcast, newspaper, magazine, and online formats, including Patch.com, Milwaukee Magazine, Wisconsin Public Radio, El Conquistador Latino newspaper, Investigation Discovery Channel, History Channel, WMCS 1290 AM, WTMJ 620 AM, and Wispolitics.com. She is the recipient of the 2008 UWM Alumni Foundation teaching excellence award for academic staff for her work in media diversity and innovative media formats and is the co-founder of Media Milwaukee.com, the UWM journalism department's award-winning online news site. McBride comes from a long-time Milwaukee journalism family. Her grandparents, Raymond and Marian McBride, were reporters for the Milwaukee Journal and Milwaukee Sentinel.

Her opinions reflect her own not the institution where she works.