Do you remember White Tower?

My grandmother sure does. As the wife of a Wisconsin Electric employee, she would pack up her three children every fall for school physicals at the Public Service Building on 2nd and Michigan. The bus ride from Oak Creek was a real expedition, but if the kids behaved, the day would end with stops at White Tower (600 N. 2nd St.) for a bagful of burgers and Fourth Ward Square for a picnic. Sixty years later, she still describes these annual White Tower visits with a sense of wonder and amazement.

And so it was, for the two generations of Milwaukee children who came Downtown to White Tower before the first McDonald’s. "As a kid growing up in the Depression, a hamburger and a chocolate malt at White Tower was a rare treat only experienced on special occasions – the Fourth of July, Christmas shopping, vacations and always on the bus or streetcar," reflected a Milwaukee Journal editorial in 1975. White Tower wasn’t just a Milwaukee restaurant. It was a Milwaukee tradition, woven so deeply into Downtown’s densest blocks that it couldn’t have survived anywhere else.

Borrowing heavily – perhaps too heavily – from the hot-and-now success of White Castle, John and Thomas Saxe opened their first White Tower location at 1502 W. Wisconsin Ave. on Nov. 17, 1926.

The first White Tower, 15th & Wisconsin, open Nov. 17, 1926.

The first White Tower, 15th & Wisconsin, open Nov. 17, 1926.

Their growing movie palace empire already included the Princess, Alhambra, Wisconsin, Oriental, Garfield, Tower and Uptown Theaters. Within a year, there were six White Tower locations in Milwaukee and one in Racine, with many locations within walking distance of a Saxe Theater.

These "lunchrooms" were remembered for their unique architecture: white, impossibly clean, stylized medieval castles. The bright white buildings were intentionally designed to contrast coal-stained Downtown buildings. Restaurants were laid out in polished chrome and white tile. Staffed by "Towerettes" – female employees in white nurses’ outfits – the original White Towers were immaculate.

White Tower, 600 N. 2nd St., still sporting its original crown.

White Tower, 600 N. 2nd St., still sporting its original crown.

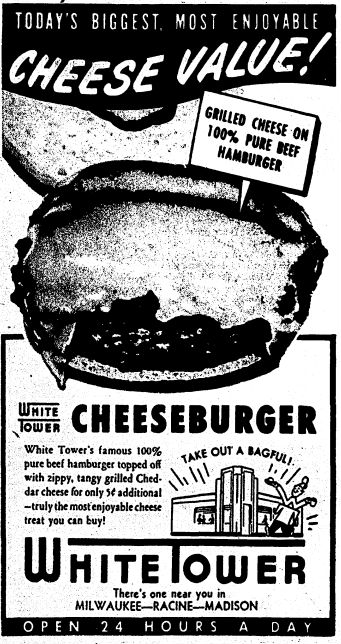

In Milwaukee, cheap meals usually meant tavern food, served in a loud, raucous and crowded space, so the Saxe brothers used white to sell the idea that dining out could be both affordable and clean. The lunchrooms served a simple menu for a blue collar crowd, including 5-cent hamburgers, coffee, ham sandwiches, pie, donuts and soda, all available 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

"They made an inexpensive meal in clean, shiny buildings for working people," comments architectural historian John Margolies. "They did for hamburgers what Henry Ford did for the automobile."

Hamburger prices stayed at 5 cents until 1941, and coffee was sold for 5 cents until 1950. For decades, White Tower offered free meals on Christmas Day, "just to make sure that no single man, whether black or white, resident or transient, should go hungry." The 24-hour restaurants never ran out of food – except on July 26, 1946, when a gas company strike caused many Downtown restaurants to close. White Tower stayed open, offering milk, pie and coffee until the grill came back on.

White Tower Boy, the official mascot.

White Tower Boy, the official mascot.

In a time before cars, the Saxe brothers strategically located their Towers at the intersection of train and trolley lines. For example, the most memorable 2nd and Michigan location was mere footsteps away from interurban trains, the streetcar exchange and the Milwaukee Road terminal. Guaranteed to collect foot traffic at busy crossroads, White Towers became the workingman’s lunch counter. From the Great Depression until World War II, the shops were almost entirely men’s spaces. After World War II, White Tower marketed jobs almost exclusively to women.

"Neat? Presentable? Be a White Tower Girl!" beckoned the ads, promising an easy way to boost the family budget. White Tower also promised comprehensive benefits, including health insurance, free uniforms, free meals, fast-track promotions and even paid time off. Many of these benefits were totally unknown for women in the workplace at that time. "No restaurant organization anywhere can top White Tower when it comes to working conditions," promised the ads.

The original White Tower designs looked very familiar – not only to customers, but to competitor White Castle, which had already opened in 1921 with identical architecture, products and slogans.

Flabbergasted by the Saxe’s success, White Castle took them to court for trademark infringement and won. The U.S. Court of Appeals ordered White Tower to change its lookalike buildings, stay out of White Castle’s markets and pay $100 royalties for each location they’d opened. To ensure compliance, the Saxes would have to send photos of every White Tower location to their competitor – and pay licensing fees exceeding $80,000.

While the courts ruled in favor of White Castle, the zeitgeist ruled in favor of White Tower. Art deco and international style were just coming into vogue, and the chain’s conversion from medieval lunchrooms to streamlined modern coffee shops was perfectly timed. White Tower rapidly expanded to 10 states. Later, they would add turquoise and orange neon signage to the buildings, complementing the pure white with a splash of eye-catching color.

Unfortunately, White Tower didn’t update its operating model for car-crazy, postwar America. Although the chain experimented with roadside locations in the 1930s, they remained firmly planted on Downtown city streets. When foot traffic disappeared, many locations found themselves landlocked at undesirable addresses. At a time when drive-in restaurants were the rage, most White Towers didn’t even offer parking spots.

The last Milwaukee location opened at 1136 W. Wells St. in 1949. This would be the highest height of the White Tower empire. With 230 nationwide locations, including 12 in Milwaukee, the chain entered the 1950s ready for limitless growth.

The expressway era changed everything. A decade later, half the stores were already gone, and the surviving locations weren’t faring well. White Tower’s tiny stores had always existed in those in-between urban spaces that were too small for any other commercial development. This strategy didn’t anticipate that those in-between spaces would someday be needed for parking.

By the early 1960s, Water Street north of City Hall had become a Skid Row. The White Tower at 163 E. State St. was part of a seedy block of bars, boarding houses and empty storefronts. Once the lunchroom for city officials, White Tower had fallen far out of fashion. The entire 900 N. Water St. block was demolished between 1963 and 1966 and redeveloped as the Performing Arts Center in 1969.

In September 1962, City Federal Savings targeted White Tower #2 (723 N. 6th St.) which had stood midblock between Wisconsin and Wells since 1927. They didn’t just evict the tenant – they also sued to prevent White Tower from excavating and moving the restaurant, claiming it would constitute "invasion" of their future parking lot. These restaurant moves were not uncommon; in fact, the first White Tower was relocated from 1502 to 1538 W. Wisconsin Ave., where it remained until the late 1950s. In the end, White Tower won the case and set up shop at the end of the block.

The iconic 600 N. 2nd St. location fared the best. Beloved by Downtown workers and visitors alike, the last White Tower was featured in local guidebooks, architectural tours and even tourism advertising. Serving up low-cost meals and a safe space, White Tower was a critical cornerstone for the single room occupancy (SRO) residents living at the nearby Antlers, Plankinton, Randolph and Belmont Hotels. Honoring the company’s 50th anniversary, the Milwaukee Landmarks Commission nominated the North 2nd Street location for historic designation in September 1976.

Nobody expected 1976 to be White Tower’s last year of business in Milwaukee. But that’s exactly what happened. Following a corporate reorganization, it appears the last three locations either lost their franchises or chose to exit the chain. 601 W. Wells St. became "Patty’s Place" for a short time but was demolished for a Firestone Auto Shop in June 1976. The 1136 W. Wells St. location was acquired by the Ham ‘n Egger chain. And 600 N. 2nd St. became the Chuck Wagon Restaurant until 1980.

The last White Tower in Milwaukee became the Chuck Wagon in 1978.

The last White Tower in Milwaukee became the Chuck Wagon in 1978.

After 50 years on 2nd and Michigan, the last White Tower in Downtown Milwaukee was demolished for Grand Avenue parking. Despite being architecturally sound, White Tower was another relic of yesterday’s Downtown. Like the SRO hotels, it was considered a sign of blight in the "everything must go" mindset of 1980. There were no calls to restore or relocate the historic building, or incorporate it into the new development.

Considering the 1979 release of White Towers, a pictorial history celebrating the chain’s origins in Milwaukee, it’s remarkable that – only a year later – nobody fought harder to save the last surviving location.

A single White Tower Restaurant still stands today in Toledo, Ohio. White Castle has maintained their historic distance from Milwaukee, with only one Wisconsin location (Pleasant Prairie) and no current plans for more. The White Tower Archive, representing over 50 years’ worth of company history, was recently donated to Penn State University.

But ninety years after the first location opened on 15th and Wisconsin, few Milwaukeeans even know that White Tower ever existed.