You meet the most interesting people while digging around in archives and museums. Bill Mosby is surely one of the most interesting that I've come across.

Born in 1916, Bill Mosby did a bit of everything once he arrived in Milwaukee from Memphis, Tennessee – where he worked in the fields picking cotton: he was a poet, a union leader, active in politics and a restaurateur.

According to Ben Barbera, who wrote about Mosby in his UWM dissertation, "An Improvised World: Jazz and Community in Milwaukee, 1950-1970," Mosby stopped off in Chicago for a few years where he found work as a doorman at a nightclub. In 1935, Mosby moved to Milwaukee where he again worked as a doorman at a nightclub until it closed in 1939."

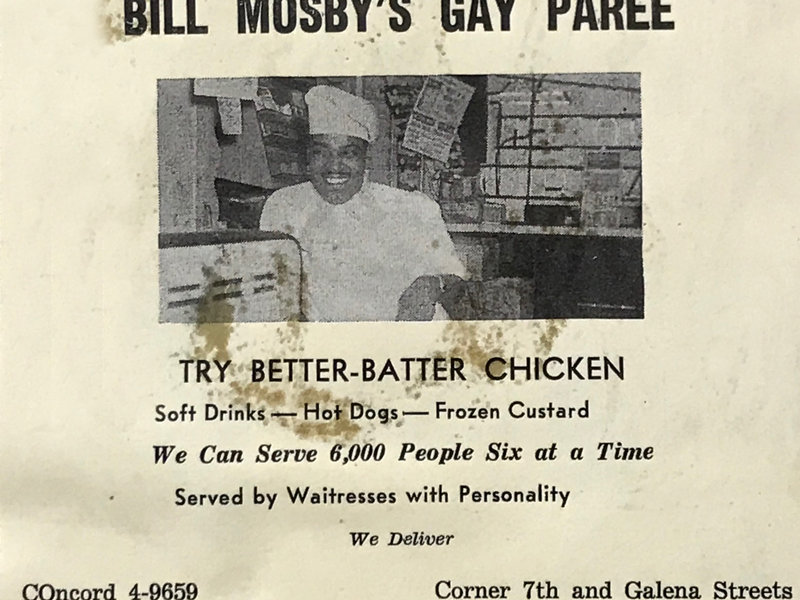

I first "met" Mosby while visiting the Wisconsin Black Historical Society, 2620 W. Center St., where an ad for Mosby's restaurant – Bill Mosby's Gay Paree, on 7th and Galena in the heart of Bronzeville – is displayed on the wall.

The phrase "better-batter chicken" and Mosby's infectious smile hooked me, two of my favorite words – frozen custard – reeled me in, and the tagline, "we can serve 6,000 people six at a time" – suggesting Gay Paree was an extremely petite version of the city for which it was named – and "served by waitresses with personality" had me sold.

I had to know more.

Though the Gay Paree ad is undated, I learned that Mosby – who had "hoboed" his way to Brew City as part of the long Great Migration of African-Americans from the South to the North – also had a place in the mid-'50s called "Bill Mosby's Chateau," nearby at 836 W. Walnut St. According to Barbera, Mosby closed the Chateau, which was a tavern that hosted live jazz, around 1957, "because he could not make enough money to take care of his 11 children."

In the early '50s, he ran Bill Mosby's Chicken Shack at 1516 N. 8th St. It's possible these were all basically the same restaurant with different names in different locations.

One interesting news clipping about Mosby dates to 1945, during his pre-restaurant days – when he was working at A.O. Smith and, simultaneously honing his poetic sense.

"To most war workers," wrote an unnamed Journal reporter, "the humming of a lathe may be just plain noise, but to Bill Mosby, 28, of 1830 N. 10th St., it is music and poetry. All day long he stands at his machine and translates the noises and rhythms into songs and poems which he writes during his spare time."

Though Mosby's music – rarely referenced outside that lone newspaper article – hadn't earned him fame and fortune at that point, he was getting noticed, according to the article, which was accompanied by a great photo of a smiling Mosby, complete with tobacco pipe.

"One of his songs is being plugged by Rochester, Jack Benny's stooge. He introduced Bill's song, 'Boy, What A Gal,' during his personal appearance tour recently. Jimmy Lunceford features 'It's Only You,' which Bill wrote in conjunction with Frank Keppler, a local musician who works in the same war plant. Louis Jordan, whose Tympani Five recordings are big gits with hot music loves, is boosting two of Bill's compositions, 'Meet You on the Outskirts of Town' and 'Throw It Out of Your Mind.'"

Even then, just a decade after his arrival in Milwaukee, Mosby was a community treasure. (Did I mention Mosby also founded the Sickle Cell Anemia Foundation and, at nearly 70 years old, had his first visual arts show?)

"Bill is a leader in local Negro community affairs and a sixth ward celebration is hardly complete without a poem written for the occasion by big Bill Mosby. He is a machine operator in one of Milwaukee's largest war plants. The company recently presented him with his sixth merit award for suggestions which boosted production."

A year earlier, one of big Bill's poems, "My Comrades and I," was read as part of an honor roll project paying tribute to neighborhood residents serving in the war. A plaque in their honor was placed outside Roosevelt Junior High.

According to Barbera, "Mosby’s life in Milwaukee was both exceptional and typical of the black migrant experience. On the one hand he was able to find industry jobs, and eventually fought through remaining elements of discrimination to land a semi-skilled position. However, the economic realities, and the physical effects of the work, took their toll.

"Then he was able to reinvent himself as a businessman in Milwaukee’s Bronzeville district. But the declining economic status of the area, as well as the effects of early urban renewal and expressway projects, meant that for many owning a business was no longer tenable in 1960s Bronzeville. Mosby then found a decent job as a longshoreman, but again the effects of the economy in the city – this time the shift away from manufacturing

– and the physical demands of the job, meant that he had to retire early.

"Nonetheless, Mosby was able to do important things for his community and his family throughout his life, and despite hardships was able to realize some aspects of the migrant’s dream."

If Mosby was a gift to Milwaukee, this son of a sharecropper and a housekeeper seemed to think the reverse was true, too.

"When you are young and black and poor and growing up in the South, the Dream is Chicago," he told the Journal's Melita Marie Garza in 1989. "But I didn't really find my dream until I moved to Milwaukee."

In later years, Mosby appears occasionally in newspapers via his work as a leader of the longshoreman's union and as a political delegate. Interesting, years after his Bronzeville neighborhood was erased from the map, Mosby still lived at 7th and Galena, where in 1991 he was rescued by firefighters from his burning apartment at 792 W. Galena St.

"All the best things in my life happened to me on Walnut Street," he told Garza. "I met my two wives on Walnut Street. I got my education on Walnut Street. I never would have had the opportunity to do all the things I've done here in Milwaukee had I stayed in the South."

You can't help but wonder if, in those days, Mosby – who died in 1993 – would step out of the Plymouth Apartments, look around and see a mental picture of all the shops and taverns and theaters and homes that once occupied the area. Big Bill was a poet, so I bet he did.

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has be heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.