It may seem curious to us now, but at the height of the Cold War, the Milwaukee area was ringed with defensive missile sites.

At the time, however, Brew City was still the Machine Shop to the World and our heavy industry played a key role in the defense of the country. Why wouldn’t enemy bombers want to come take us out?

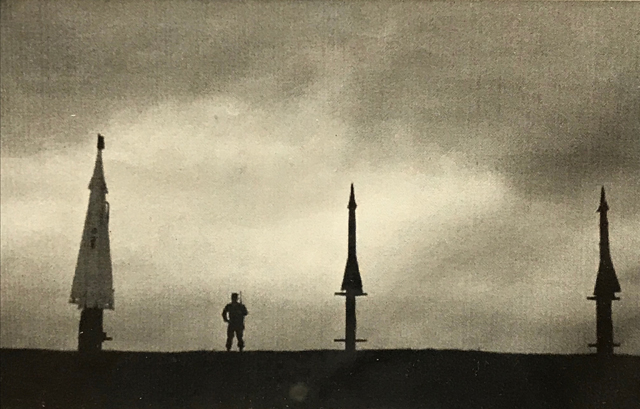

Along with some other American towns, Milwaukee got eight Nike Ajax Missile Sites, including one right near Downtown on what is now the Henry Maier Festival Park, in 1956. Some sites had as many as a dozen Nike Ajax missiles pointed at the sky, ready to shoot down enemy bombers.

Three of those sites – including the future Summerfest grounds – were "upgraded" to nuclear Nike Hercules weapons.

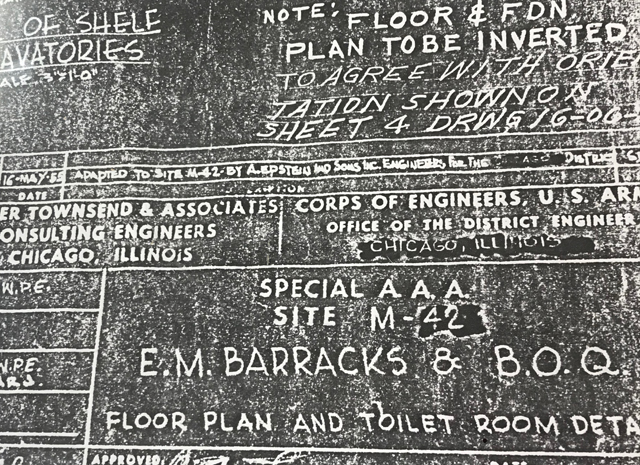

The sites were designed and built by the Chicago District of the Army Corps of Engineers and were staffed with Army personnel.

While most of the installations are entirely gone, some have left remnants, notably the one in Waukesha.

Another, however, is in Cudahy, where site M-42 was home to six Nike-Ajax missiles from 1956 until 1961 and a complex of five buildings, three of which still stand, whose placement was surely related to the proximity of Ladish, Bucyrus-Erie and other major manufacturers, as was site M-20 in Grant Park.

A full list of sites around the country can be found here.

In 1975, the site became home to the Warnimont Park Senior-Youth Center, which later became the Kelly Senior Center, named in honor of former Cudahy Mayor Lawrence P. Kelly.

It remains the Kelly Senior Center, 6100 S. Lake Dr., today, and many of the folks on site on any given day vividly remember when the missiles poked their warheads out of the ground just to the north in Warnimont Park.

Unison, which runs the Kelly Center – as well as a few others funded by Milwaukee County – invited me down to take a look and to chat with some of the seniors eager to talk about the Cold War in Cudahy.

When I arrived, I saw two low, one-story buildings – one facing Lake Drive, the other nearby, running perpendicular. Otherwise, the site is mostly wooded. A smaller third building is out back.

The two demolished buildings that were part of the complex stood behind the building parallel to Lake Drive.

Stepping inside, Dianna Bartelt, manager of the Kelly Senior Center, showed me around.

"This is what we call our main hall," she says as we stand in the north wing of the U-shaped building. "This used to be the barracks. Now, it's our multipurpose room. Not only were there barracks in here, but this is where the offices were and the day-to-day functions of the stuff they did, as well.

"This entire wall where the bathrooms are, that was an open latrine."

Now, there are shuffleboard courts painted on the floor, though they don’t get much use, says Bartelt. But don’t let that fool you, Kelly offers a wide variety of activities and wellness programming for seniors, 50 and older. For example, one room has a quilt loom, another is a ceramics studio, there’s an impressive fitness center.

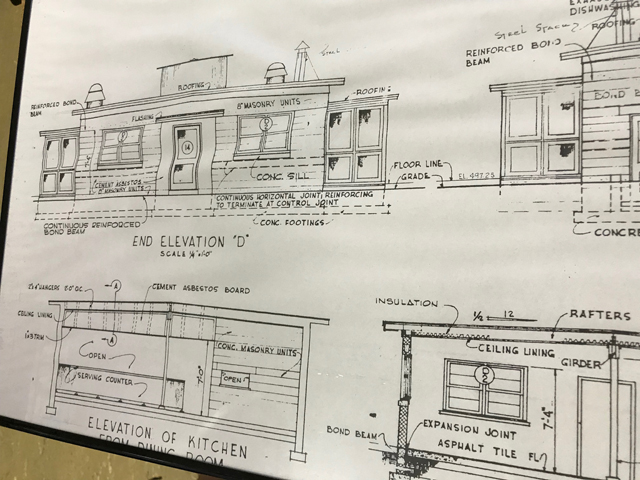

Another room in this building is a library and in here there are displays about the missile site, with photographs, maps and articles. Laid out on a table are original blueprints for the buildings.

"Some of them had to be torn down," says Bartelt. "There was a kitchen building that is gone. These two buildings are the only remaining buildings, and there have been some changes to it, of course."

Pointing to a small square on one of the maps, she adds, "This building is still there, but it's just a storage shed."

The other remaining building is the senior center dining room (pictured just above), where thousands of meals each year are served. And it’s a great use for a building that used to be the mess hall for the soldiers stationed here.

According to a Wikipedia page about the Nike-Ajax sites, the missile command center was located about a half-mile north in Warnimont Park and the missiles were located on land another half-mile north of that, now owned by Cudahy High School. Others, however, suggest the missile silos were where Warnimont Park golf course is.

Wandering up that way in the woods, I didn’t find any remnants of the silos or the command center – some of which, I’m told, maybe have eroded into Lake Michigan in the intervening decades – but a friend, Christina Ward, has explored the area more thoroughly and sent me photographs of bit of concrete and things that may or may not be from the missile site.

"I wish the other buildings still would have been here because I would have had a field day just climbing through this place," says Bartelt, who clearly loves where she works.

"Seniors are my life," she says. "I'm gonna cry, I'll tell you that right now. We provided almost 6,000 service units to area seniors (last month). Which means 6,000 times someone came here and did something. Providing that type of service to forgotten clients ... the great things that Unison does for the seniors is just tremendously touching."

With that we head back inside and I’m greeting at a round table occupied by Charlene Stevens, Ken Kovac, Rose Marie Roman, and Michael Nowak and Jackie Brebar, who are married.

We go around the table and each has something interesting and enlightening to share.

Stevens, who goes by "Charlie," wandered in eight years ago asking to plant some flowers out front and has been in charge of the gardens at Kelly ever since. She begins.

"When this was the Nike site, my dad’s family homestead is on the east end of Hammond Avenue, which is just walking distance from here, and his younger sisters were a year older than me, and so my younger sister and two of his sisters and I would buy a bag of candy bars, which were a nickel or less at that time, and bring them down and give them to the soldiers through the hurricane fence. I was probably 9, so it was a lot of fun. My mother played the violin – she was in the Milwaukee Symphony when she was very young – and she would come twice a month on Wednesday night and play her violin here.

"When they moved the missiles out – when they emptied the silos – my dad got us out of bed and we came down and watched them put them on flatbed trucks. He said that was an important part of history, so get up. It was 3 o'clock in the morning and they hauled them down Highway 32 and they took them to I think Fort Sheridan in Illinois.

"It was a part of my childhood. It was a fun part, it was never a scary part for me."

For Kovac, another Cudahy native, the missiles were part of a more ominous story.

"I grew up in the older part of the city, where my grandparents built a home in 1917, and my grade school was a block away," he says, "and my memory of the installation was of fear and nervousness. I remember the sirens going and we'd have to duck and cover in school. That seemed so senseless because we'd be wiped out. The desk wasn't going to do anything but we'd be practicing that all that time and that would further instill the fear in me.

Nowak also remembers the missile installation from his school days. And, he even remembered being inside the building in which we sat talking about the past.

"I remember this area vividly as a child," he says. "The first time I came here was on a class trip when I was at Warnimont Street School and we took a class trip to this facility. I remember the building we are in now, I remember the building across the street, and the silos where they kept the missiles, about a quarter-mile down the road in what is now called Warnimont Golf Course area.

"The missiles were not poised to knock out other missiles, but to knock out the Soviet bombers that would be bringing nuclear bombs. The bombers were the equivalent to our B-52 bombers of today. You’ve got remember that Milwaukee was ground zero because we were the machine capital of the world. Ladish, Kearney & Trecker, International Harvester, Cutler Hammer, Allis-Chalmers, Louis Allis.

"Milwaukee was supposedly was well-protected, but like the gentleman over here (Kovac) was saying, we would practice this duck and cover. You’d hear the air raid sirens and everyone would get up, get underneath your desk or go out in the hallway and go underneath the coat racks and cover your heads and kneel down. But that was senseless because by the time you get up you'd be vaporized.

"The American Civil Defense gave people blueprints how to build air raid shelters in your basement. And in the area that we grew up in, in the Town of Lake, everybody had an air raid shelter in their basement, except our house. It really wasn't protection, it was just kind of a facade, you couldn't defend against something like that.

Nowak’s wife, Jackie Brebar, continues:

"I spent my summers in Oak Creek – back then it was Carrollville. I stayed with my aunt and uncle in the summer time and we'd always make my uncle drive us by here, so we could see the missiles, because sometimes they would be out. For me it was a very scary time. I said, ‘Mom we gotta build a shelter! We gotta build a shelter!’ And she'd be like, ‘You know if they come, honey, we're gone." Mom was a realist.

"But I remember, at one point, there was actually a run on the grocery stores here where they emptied the shelves and everything. That was a total panic. During the Bay of Pigs (Invasion, 1961), The grocery store shelves were empty; everything was sold out. People were just hoarding everything that they could get their hands on."

Brebar even got to go inside the missile control building, she says.

"I was lucky enough to get one of the guys to let my sister and I go into where the trigger was," she recalls. "Where Grange Avenue comes down and it makes a T into Lake Drive, they made a road up there and then the little unit where the guys would be 24 hours was in there and we got to go in the trigger room."

Luckily for all of us, that trigger was never activated.

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has be heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.