Artist Reginald Baylor recently opened his new studio at 211 W. Florida St. in Walker’s Point in a low-slung, two-story building that actually carries three addresses: 211, 215 and 219. But more importantly, that rather unassuming-looking building, also carries a lot of years and some really interesting history, too. (Note: the art studio is no longer located in this building.)

For many years, most recently, the building – with its two retail spaces downstairs and two apartments upstairs – has served, seemingly on and off, and without great attractiveness, as a tropical fish store.

In recent years, says co-owner Dieter Wegner – who owns a number of buildings in Walker’s Point, including the ones that house Movida and the new Walker’s Point Music Hall – the building has been "neglected passively and ruined actively."

After.

Before. (PHOTO: Ryan Pattee)

When, less than a year ago, Wegner saw the place, he his friend and fellow developer Ryan Pattee, who says, "I always wanted to do a project in Walker’s Point."

"I said, ‘you’ve got to do something with the place’," adds Wegner. When Pattee chimes in, "I said, ‘let’s do it together’," Wegner fires back, "I said no f*cking way.

"It took him two weeks to convince me."

After.

Before. (PHOTO: Ryan Pattee)

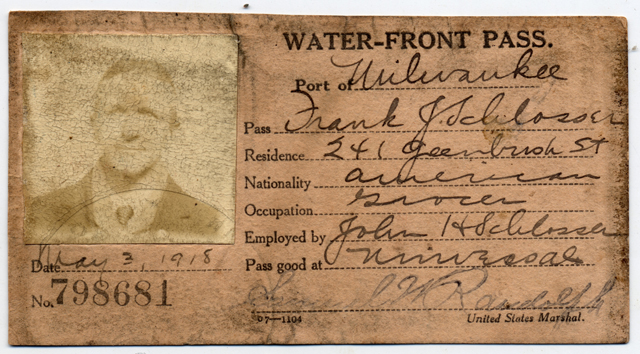

Part of the allure of the place, which was built in 1865, for the new owners was the building’s long and rather unique history as a ship chandlery – a store that supplied ships calling into Milwaukee – run by John H. Schlosser, pictured below on the steps out front, for decades.

Honest John Schlosser

"Honest John" Schlosser was born in Prussia around 1846 and arrived in Milwaukee with his family about 1850, where he attended school. When Schlosser was 14, his father "hired him out" to a shopkeeper on the corner of 3rd and Florida Streets.

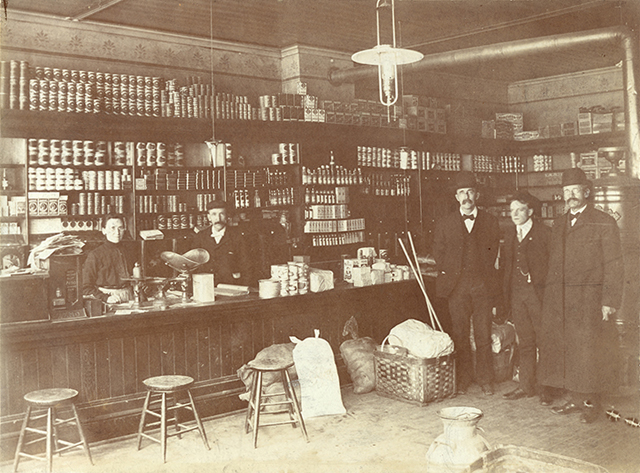

Honest John outside his shop (above) and behind the counter (below),

with his son Frank, second from right.

Later, Schlosser would recall that his work as a clerk earned him $48 the first year and double that the next. He told a newspaper in 1932 that he used the money he earned across his five years as a clerk to purchase 10 acres of land and build a log cabin on it for his parents.

By the time he was 20, Schlosser had the urge – though not the money he’d earned (see above) – to strike out on his own. So, he partnered with a fellow from Burlington to open a grocery in space rented from his former employer.

After about a year, Schlosser would remember in 1932, the landlord wanted to have his space back, so "I took this place. It was an old warehouse, held by the Fifth Ward Bank. My partner (from Burlington) meantime sold out to me. I’ve been here ever since – 65 years."

Schlosser appears to have gotten into the ship chandlery business rather by accident, though also rather quickly, according to a 1923 newspaper article about his business headlined "The Sea-Going Grocery Wagon:"

"This marine delivery has been going on for 57 years," wrote the Milwaukee Journal Magazine. "In 1866, John H. Schlosser ... sold groceries to the families of the lake seamen who lived on the South Side. What was more natural than that the captains should request the grocer to deliver supplies to the schooners, and brigs that put into Milwaukee harbor with cedar posts crowding their decks.

"Years went on, the captains moved from the South Side; the family trade of the grocery grew less, while the marine business increased. By and by here was John Schlisser supplying flour to a ship that moved by steam ... fleets of wood of old days, and fleets of iron that cruise the lakes today, both are on the books of the old grocery house. In the little office where John J. Schlosser works over a ledger a pictures of famous sailing vessels. Beside them hang portraits of the good seamen who took them out.

"When a storm drives passing ships into the harbor of refuge it is the Schlosser launch that runs out with supplies. Along about Christmas time, when navigation is finally closed, the Florida street grocery takes on the character of a snug harbor. The lake captains come in to visit their old friend, John H. Schlosser. The cooks come in because the captains are there. Many a ship secures its cook for next season in the same place it gets its supplies. When spring comes, the 30 or 40 ships that have wintered in Milwaukee, fit out, and then the launch takes out everything from blankets to olive oil and from pillow slips to beeswax."

Business must’ve been pretty good from the get-go because by 1867, Schlosser put an addition on his Florida Street building, Pattee and Wegner are guessing that, based on construction evidence they found during the renovation, the addition was vertical, adding a second floor, rather than horizontal.

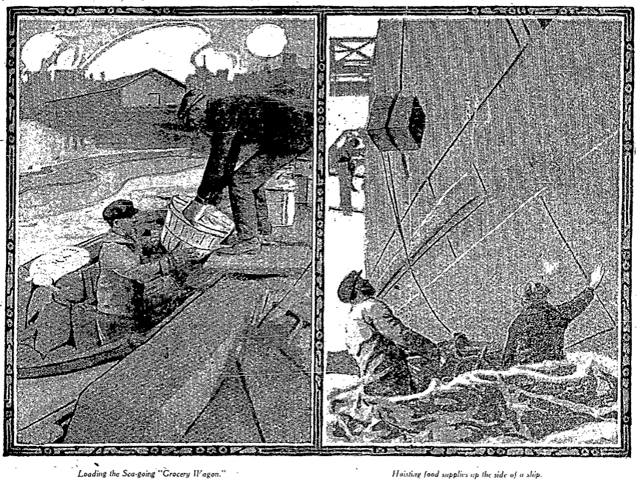

Two views of the Schlosser launch on the water.

Schlosser also became well-known in the community over the years, and was a stockholder in the German-American Bank that was located on 2nd and National.

Research Pattee did for a historical panel about the building helps add more detail to Schlosser’s story...

"His first contract was to supply a government revenue cutter (the revenue cutters were the precursors of today’s U.S. Coast Guard). Dennis Sullivan, who was the captain of the schooner Moonlight, sent him several ship captains to trade with. That marked the beginning of Schlosser’s long career of supplying the schooners and steam ships.

"Schlosser invested in property in Thompson, Upper Michigan. The land, was periodically logged and the trees sold. In November, 1912, the three-masted schooner Rouse Simmons, also known as ‘Christmas Tree ship,’ made its final stop at Schlosser’s land in Thompson to pick up Christmas trees for Chicago families. It sank in a storm off Two Rivers, never reaching its destination."

(PHOTOS: Magazine section of the Milwaukee Journal, Dec. 9 1923)

It seems that Schlosser might have actually gotten his start doing marine supply work back when he was clerking in his first job.

"It was either in ‘64 or ‘65," he told a journalist in 1932, "that I went across to deliver groceries to a schooner where Goodley’s dock was, on the southwest side of Michigan. That schooner carried lumber consigned to a Milwaukee merchant, R.B. Fitzgerald, I remember, had a fleet of schooners and so did David Vance, but that was considerably later. Those days 1,000 tons of coal was a big cargo – today 15,000 tons is no load at all.

"We had plenty of time to stock the boars then – they’d come in and tie up for several days. They were unloaded by horses. It wasn’t like today. Why, sometimes now we have only a couple of hours to stock a boat."

"In the early days we sold the boats no milk at all. Corned beef, salt pork, hardtack, that was what the crews had to eat – and the stewards (they were called ‘cooks’ then) baked the bread. Today we sell ‘em everything – whole cases of oranges, grapefruit, strawberries, bananas by the bunch, fresh vegetables, fresh bread, even ice! Sometimes we get a call for hard coal – the stewards use it for for cooking. We don’t stock that, of course, in the grocery business, but we have a launch and get it to the boat."

"Many times boats are outside (the port), lying there, waiting to come in. They have to be supplied and for this work we keep a high powered launch. A captain came in to see me last summer – reminded me of the time I waited two hours in the drizzling rain until he could get alongside to take on two gallons of milk and six loaves of bread. He was captain of the City of Berlin and when he called me, he asked if I could get the stuff down to him for supper – he was on his way to Commerce Street to unload some coal. Everyone had gone home. I was alone. I took the streetcar. When I got down there, no boat. Waited an hour. When he did whistle for the Holton Street viaduct, it took him an hour to get up enough steam to go through. I waited, though, until he got alongside and took his milk and bread!"

This is the kind of thing that helped earn Schlosser the moniker, "Honest John."

After Schlosser

Alas, no one lives forever, even if it seemed like Honest John might make a go of it and he died, at age 88, still working, in 1934. His son Frank took over until his death in 1940 and in 1943 the family sold on a land contract to Jacob "Jack" Gronik, who continued in the food business there until the late 1950s, when the Jack Gronik Company moved to 1361 W. North Ave., at some point becoming an "edible nut sales firm."

Tragically, Gronik and his wife Ada died in a fire in their Fox Point home in 1965, faulty wiring blamed as the culprit. Gronik had paid off the Florida Street land contract just a few years earlier.

After the grocery closed on Florida Street, a number of businesses came and went, including Mik-Wood Specialty cabinet shop and Wachter Leather in the 1960s and ‘70s, Jonathan Voss stained glass studio in the early ‘80s.

The building today

In 1982, Tom Wagner bought the place and converted it into his tropical fish store, which leads us to today, as Wagner sold the building to Pattee and Wegner.

Upstairs, I should add, remained apartments across all these decades and were inhabited, though not so much "habitable," when the current owners took over.

The second floor, like the first, has been thoroughly rehabbed and one unit is rented, while the other, larger space (pictured above) – with exposed rafters and the original 1860s hardwood floors (peek through the window to get a glimpse of the wood on the staircase up!) – is rented via Air BnB.

The stairs.

Upstairs floor.

If you stop in to see Baylor’s studio – and you should; he’s one of the city’s finest artists – you’ll see how Pattee and Wegner transformed the retail space, which had been chopped up with an array of interior walls.

Two views inside the gallery.

One of the main challenges was dealing with the fact that settling had caused a pitch from one corner diagonally across the space to the opposite corner of what Pattee estimates was at least two feet. That was solved by raising the floor.

(PHOTO: Ryan Pattee)

Next up, the owners plan to take on the space behind the building to create a more attractive and useful patio. As always, Pattee says he remains dedicated to doing "period-sensitive renovations," and you can tell that this quiet building with a long Great Lakes maritime history has got more than a few years left on it.

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has be heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.