It was called the "saddest week in Milwaukee's history." 150 years ago today, on April 14, 1865, Abraham Lincoln was assassinated. He died five days after Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, effectively ending the Civil War.

As one early history of Milwaukee records, "The city was hushed in grief. Silently and sorrowfully the buildings, many of them still gaily flaunting the joyous decorations of the week before, were clad in the habiliments of woe."

Many of those Milwaukeeans were doubtlessly remembering Lincoln’s visit to the city, just six years earlier.

Before Lincoln became the 16th president, the citizens of Milwaukee had an opportunity to hear and see the up-and-coming Illinois politician.

Lincoln was already a well-known figure. His fiery debates with Stephen Douglas won Lincoln national prominence. His speech the previous year, which concluded, "A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe this government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free" was widely republished and admired throughout the state. It was only natural the directors of the 1859 Wisconsin State Fair invited him to speak.

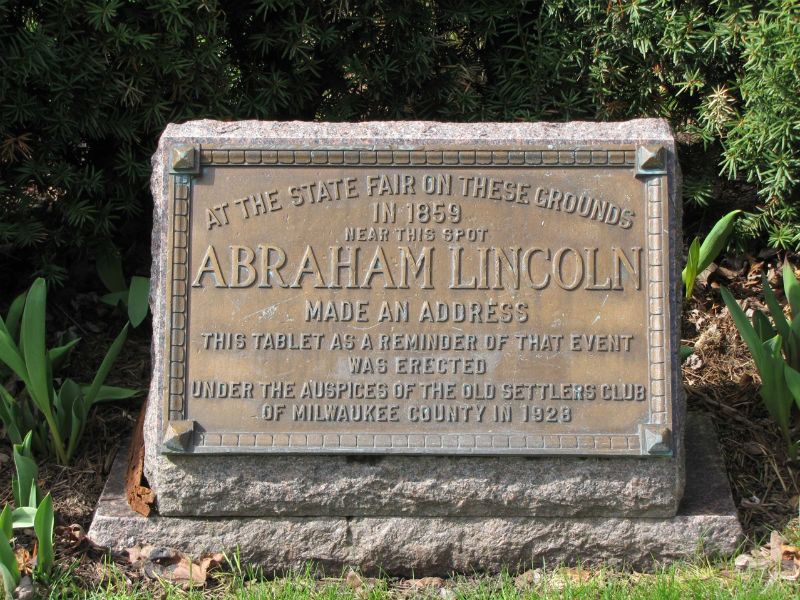

The fairgrounds were then located between Wisconsin and Highland and from 10th to 13th Streets. The spot where Lincoln delivered his speech is just north of today's intersection of 12th and Wisconsin, then on the edge of town. A small historical marker at 13th and Wells commemorates the occasion.

Lincoln, dressed in a black frock coat and his customary "stove-pipe" hat delivered his speech in his surprisingly high-pitched voice. His honorarium for the speech was $150, a very good fee in 1859.

Mindful of his audience as any good politician must be, Lincoln mostly confined his remarks to agriculture.

"One feature, I believe, of every fair, is a regular address," Lincoln began, "The Agricultural Society of the young, prosperous, and soon to be, great State of Wisconsin, has done me the high honor of selecting me to make that address upon this occasion – an honor for which I make my profound, and grateful acknowledgment.

"I presume I am not expected to employ the time assigned me, in the mere flattery of the farmers, as a class. My opinion of them is that, in proportion to numbers, they are neither better nor worse than any other class; and I believe there really are more attempts at flattering them than any other; the reason of which I cannot perceive, unless it be that they can cast more votes than any other. On reflection, I am not quite sure that there is not cause of suspicion against you, in selecting me, in some sort a politician, and in no sort a farmer, to address you.

The speech went on at great length and touched upon a variety of agricultural topics. For example, Lincoln envisioned a time when steam powered machines would plow fields.

As Lincoln's speeches go, this one "suffers from tedium," in the succinct description of the website Abraham Lincoln Online. Still, historians say the speech is significant in understanding Lincoln's thoughts on agriculture and especially the importance of free labor (as opposed to slave labor).

Having given the crowd a good, solid $150 worth, Lincoln wrapped up his remarks by noting that the prizes ("premiums") were to about to be awarded:

"Some of you will be successful, and such will need but little philosophy to take them home in cheerful spirits; others will be disappointed, and will be in a less happy mood. To such, let it be said, Lay it not too much to heart. Let them adopt the maxim, Better luck next time; and then, by renewed exertion, make that better luck for themselves.

"And by the successful, and the unsuccessful, let it be remembered, that while occasions like the present, bring their sober and durable benefits, the exultations and mortifications of them, are but temporary; that the victor shall soon be the vanquished, if he relax in his exertion; and that the vanquished this year, may be victor the next, in spite of all competition.

"It is said an Eastern monarch once charged his wise men to invent him a sentence, to be ever in view, and which should be true and appropriate in all times and situations. They presented him the words: 'And this, too, shall pass away.' How much it expresses! How chastening in the hour of pride! – how consoling in the depths of affliction! 'And this, too, shall pass away.' And yet let us hope it is not quite true. Let us hope, rather, that by the best cultivation of the physical world, beneath and around us; and the intellectual and moral world within us, we shall secure an individual, social, and political prosperity and happiness, whose course shall be onward and upward, and which, while the earth endures, shall not pass away."

His talk over, Lincoln stepped down, shook hands with local dignitaries, and strolled off across the fairgrounds. Just a visiting politician from Illinois, he had the rest of the day to himself. He paused to watch a plowing contest where, a newspaper account says, his humorous commentary on the event received much laughter from bystanders. He even attended a sideshow performance of a circus "strong man."

According to the 1924 book "History of Milwaukee," Lincoln had never seen any thing like it. As the man tossed iron balls and lifted heavy weights, a delighted Lincoln repeatedly exclaimed, "By George!"

Introduced after the show, the much taller Lincoln peered down at the performer, smiled, and said, "Why, I could lick salt off the top of your hat!"

That night a crowd of political supporters gathered at the Newhall House, where Lincoln was staying (located on the northwest corner of Michigan Street and Broadway, the Newhall House was then the finest hotel in the west. In 1883, it suffered a devastating fire, which claimed 64 lives).

Standing on a box of canned goods in the lobby of the hotel, Lincoln delivered an impassioned attack on slavery. His impromptu remarks were well-received but sadly no written record of that second Milwaukee speech exists.

It was his last visit to the city. Six years later, on April 15, 1865, having fought a war to preserve the union and end slavery, Lincoln died. He was 56 years old.