Would you believe a massive Gothic convent once stood on Milwaukee and Ogden Streets, where nuns gathered around goldfish-filled fountains in elaborate storybook gardens, shady groves and stone grottos?

For 109 years, this intersection was home to the School Sisters of Notre Dame, who built the oldest of six North American provinces of Notre Dame from this location.

Faith on the frontier

It all began with Mother Mary Caroline Friess, who arrived in Milwaukee in 1851. With funding from King Louis of Bavaria, she established the first Motherhouse of the School Sisters of Notre Dame in the United States.

Three nuns and a candidate traveled with Mother Caroline on a rough, five-week journey to the New World. "The sisters were a strange sight to Milwaukee’s rough frontiersmen," wrote the Milwaukee Journal in 1958. "It was chronicled that men jeered at them and one tauntingly asked whether they had lost their husbands, since they all wore black. Sister Mary Emmanuelle responded promptly, 'One man died for all of us and only for him do we mourn.'"

The sisters settled in a small, four-room house – each with their own fireplace – on a woodland knoll vacated by a Presbyterian minister. Hidden under massive trees, the little pioneer home with four chimneys would grow into a formidable fortress that dominated the lower East Side skyline.

Upon arrival, the Convent Hill landscape was described as a "forest primeval dotted with a few frame houses separated by ravines and knolls," populated by "wild animals whose screams and howls chilled the bone from dusk to dawn." Milwaukee was barely five years old, and Wisconsin had only been a state for three years. Solomon Juneau’s store still stood near the Milwaukee River bank, hawking frontier necessities like gunpowder, scalping knives and wampum beads. Milwaukee’s population had just hit 20,000 for the first time – and would double again by 1860.

Mother Caroline later founded a convent and orphanage in Elm Grove in 1855, as well as St. Mary’s Institute in Prairie du Chien in 1872. St. Mary’s would eventually return to Milwaukee as Mount Mary College in 1928.

Castles in the sky

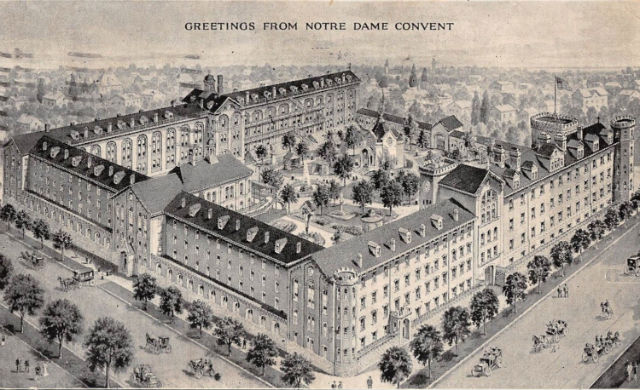

By 1868, the convent walls rose up along Ogden Avenue, Milwaukee Street and Knapp Street, with an enclosed walkway along the Jefferson Street side. Hundreds of loads of dirt were excavated from the former bluff to create a level city block. After Milwaukee Street was graded and paved, the convent looked like a fortress suspended in air.

For half its lifetime, the Notre Dame convent was one of the largest buildings in the city and a well-known landmark for early Milwaukee River navigators. The complex was frequently photographed and featured on photo postcards sold throughout the city. More than a religious institution, it became a statement of Milwaukee pride.

Beyond worship and study, Notre Dame convent was also a finishing school for girls from Milwaukee’s most elite families, including the daughters of Solomon Juneau. School attendance exceeded 400 at its peak. Until the 1890s, the sisters did not allow students to commute due to "wilderness dangers" surrounding the convent. These wilderness dangers included "undue attention" from workingmen along the nearby riverfront docks, warehouses, tanneries, breweries and taverns.

Mysterious things happened at the convent for a long, strange year in 1854. Candles disappeared from altars, pots and pans clattered around the kitchen, new garments were found clawed to shreds, and students claimed to be pinched by invisible hands. Despite being hysterical, no sisters left the convent – even when the attacks intensified over the winter. Students found muddy slush on their pillows in the middle of the night, and their nightcaps filled with ice.

In the middle of the night, the women reported hearing terrible noises, like the sound of dying pigs, and smelling unpleasant odors. Bread dough would disappear from pans already in the oven, only to turn up in the school well. Dinner went into the oven as fish and came out as beef. The house dog disappeared and was later found "gored by a great beast."

When filthy water was witnessed dripping from the ceiling on all of the students’ beds except one, an observant sister confronted the one unaffected girl. She began to laugh uncontrollably and revealed that she was cursed as long as she stayed. Her parents had promised her to a member of the Masonic Order, and she chose the convent instead.

In return, he vowed an evil hex on the sisterhood as long as she remained. The strange episodes ended when the girl was dismissed to marry her fiancée, but the curse remained. The couple lived well into their 90s in a hatefully unhappy marriage.

Not everyone was inspired by the convent’s prosperity. In August 1855, the Know Nothing Party mocked the sisters by baptizing a cow beneath the Mother Superior’s bedroom window, with its members dressed in priest costumes. The Mother Superior responded by emptying chamber pots into the street below.

On June 17, 1873, a supernatural miracle was documented here when a 19-year-old girl in the final stages of consumption was totally healed by the appearance of the Virgin Mary. This apparition generated massive attention for the growing convent.

Life inside the fortress

(PHOTO: Milwaukee Public Library Collection)

(PHOTO: Milwaukee Public Library Collection)

The convent was often called a "city unto itself," as the sisters upheld a tradition of strict self-sufficiency. They faithfully served as their own chefs, gardeners, bakers, cobblers, seamstresses, barbers, printers, musicians and any other necessary role. All religious objects – from rosaries to Communion wafers to habits to floral processions to leaflets – were produced onsite by the nuns themselves. Food supplies were maintained on the levels of Downtown’s grand hotels. At any time, the convent housed not only students and boarders, but also over 150 nuns (active, retired and infirm).

The convent was also a source of income for community craftsmen. For decades, the sisters hired immigrant workers for day labor projects. Workingmen were always warned to speak English – and watch their language – when seeing the Mother Superior about a job. "The smart few did as they were told, the others were shown the door with as little as a blink," remembered a school sister in 1957.

Notre Dame closed their learning institute in 1887 and their day and high schools in 1892. By reducing their public services, the sisters were able to make room for an additional 200 novices to join the convent. After Mother Caroline’s death in 1892, the operation seems to have become far more private, as there are few reports from inside the Notre Dame convent over the next four decades.

In August 1939, a special two-page spread ran in the Milwaukee Journal that included an aerial photograph of the Notre Dame convent, as well as photos of nuns at work, study and reflection within the campus grounds. The story was later criticized for disrespecting the privacy and solitude of the sisters, but the photographs and narrative provide a fascinating glimpse of life inside these four walls.

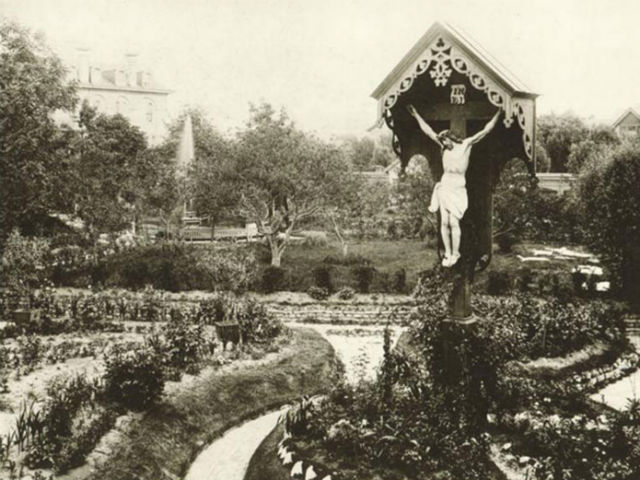

"From the garden, the appearance of the headquarters takes on the mood of a castle, with Norman turrets, bell towers, the face of an ancient clock and stained glass windows looking down on the sheltered grounds," wrote the reporter. "Here for countless summers, the sisters have walked in the shadow of greenhouses and a hooded wayside crucifix; prayed in a stone grotto dedicated to Our Lady of Lourdes; and maintained their faith and service to the city."

"Their chapel contains more than 5,000 authenticated relics of saints, and its infirmary is marked with a mammoth stone crucifix that has stood almost 100 years. Milwaukee’s oldest and most beloved Christmas picture, a painting of the Nativity dating back to 1852, still hangs here."

The School Sisters of Notre Dame had achieved tremendous worldwide influence. Mother Superior Mary Ambrosia personally supervised 12,000 sisters in 33 countries. At its peak, the province taught students in 147 Wisconsin schools, including Notre Dame and Messmer High Schools.

The castle falls

(PHOTO: Milwaukee Public Library Collection)

(PHOTO: Milwaukee Public Library Collection)

Somehow, the majestic old convent became a looming symbol of blight in postwar Milwaukee. There had been no major construction on the campus since 1893, and its coal-stained face was beginning to show its age.

"The roof consistently needs repairs, bricks have eroded, windows persist in rattling, the stairs are worn and the floors sag. The fire department keeps an anxious eye on the building," reported the Milwaukee Journal in April 1957. "Because of various fire and safety hazards, the city has opposed the continued use of that building."

In a building the size of a city block, there was only one elevator, and it wasn’t installed until 1900. City water had replaced an ancient basement well and hand pump system in 1873. The complex was wired for electricity, but the sisters still maintained gas lamps and a coal generator. Its narrow spiral staircases, dark catacombs and fourth floor garrets seemed older than creation. While this all sounds adventurous, it wasn’t practical or functional for a fleet of aging nuns.

Assessors estimated that modernizing the campus would cost almost $2 million. This expenditure would preserve their historic home but reduce mission-critical programs and services. The sisters had painful choices ahead of them: spend the money and maintain the property, or save the money and invest in their long-term future.

Their choice was unbelievable: The 280-room Notre Dame convent would be vacated and replaced by a new, modern complex in Mequon.

Mother Mary Hilaria was assigned a new project: funding the construction of a new Milwaukee motherhouse and training center. The sisters exceeded their $3 million fundraising goal with a special bond sale, then considered the largest underwriting of a Catholic institution in Wisconsin history. Ground broke June 7, 1957 for Notre Dame on the Lake.

As the sisters settled into their new lakeside home, the 106-year-old convent was slowly abandoned. Workmen surveying the building in 1958 were struck by the pristine condition of the convent interiors, which were decorated in European hardwoods, elaborate marbles and ancient stained glass. The wrecking company sold over 300,000 square feet of maple flooring, vintage wrought ironwork, steel ornamental fixtures and ancient German crystal chandeliers at rock bottom prices. Even the fountains were sold. Additional inventory was sold off at a 1959 public auction.

On Sept. 15, 1959, the Milwaukee Journal announced that convent demolition had begun. "The Notre Dame sisters have been part of the Lower East Side neighborhood longer than any of our families," read a sorrowful article. "Ours will be a sad parting."

This was no understatement. With the Lower Third Ward and East Side A projects already in flight, Milwaukee was certainly no stranger to urban renewal by 1959. This was different. The convent was one of the city’s oldest, largest and most recognized historic structures, as well as one of its most authentic blocks of European architecture. There was truly nothing like it anywhere else in Milwaukee – and has never been anything like it since.

The Milwaukee Journal took two controversial photos during the convent’s demolition. The first, on Nov. 22, 1959, showed four children (of mixed race) seated on a stoop across the street at 423 E. Knapp St. watching the demolition. The second, on Dec. 19, 1959, featured two boys playing war in the rubble of the former convent. Readers, finally lamenting the convent’s destruction, asked whether Milwaukee was building a future for its children based on war or peace.

Either way, the block was completely cleared by March 1960.

Notre Dame on the Lake grew to become a 14-building, 500,000-square foot complex. Sister Mary John, plant engineer, commented in a 1971 interview that she and an assistant managed all maintenance for the entire facility. By 1980, the sisters considered selling the land, but rejected an offer for a 450-person state inmate facility on the site. In October 1982, the Lutheran Church – Missouri Synod purchased the campus for Concordia University, which relocated here after 101 years on Milwaukee’s West Side. Although the Notre Dame convent thrived on Milwaukee Street for over 100 years, the Mequon location did not last 25.

It’s been almost 60 years since the Notre Dame convent loomed on the Lower East Side horizon. In 1960, Milwaukee’s first affordable housing for the elderly opened at this site and named "Convent Hill" in tribute to the original structure. Originally, the city planned for additional apartment towers, as well as a westward-facing meditation garden with reclaimed convent features, including a stonemason wall, paved walks and benches. City planners also claimed that the convent courtyard’s trees would be preserved with a retaining wall.

However, all that was ever built was the lone building at Jefferson and Ogden. And all that remains of the original convent is a simple bell tower in the parking lot – and a history display in the lobby.