If you like this article, read more about Milwaukee-area history and architecture in the hundreds of other similar articles in the Urban Spelunking series here.

Like lamp posts and fire hydrants, the old police call boxes that once stood sentinel on street corners all across Milwaukee have been such a part of the landscape for so long that many people don’t even notice them.

But for the folks that do, they’re a treasure, reminding us of the continuity of city life here and, thanks to their decoration, of a time when we wanted even mundane things to not only work well but to look good. We wanted them to be something to be proud of.

The heavy cast-iron boxes perched atop tall bases contained telephones from which police and school crossing guards could call in to their local precinct house, in the days not only before cell phones but before two-way radios.

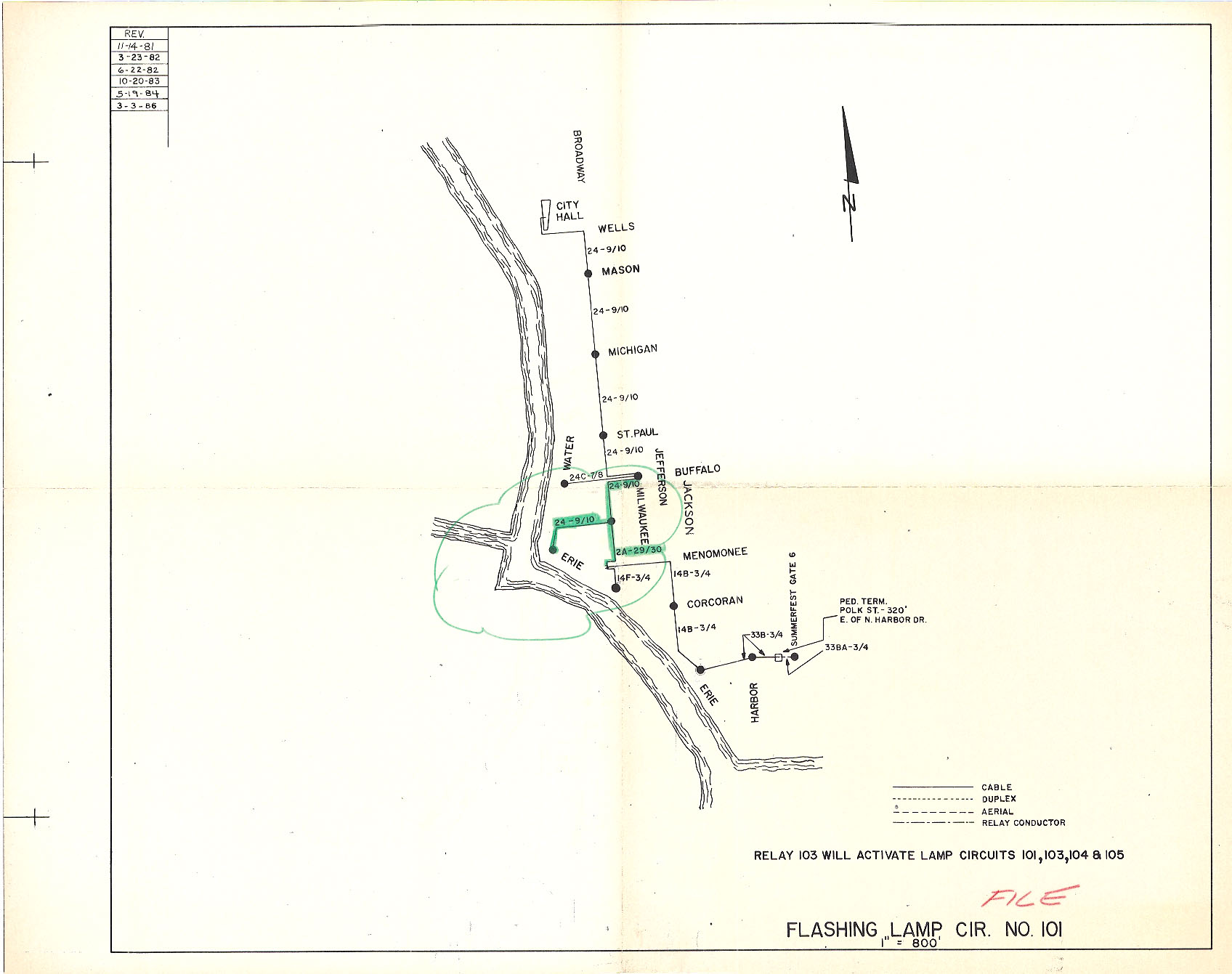

There have been multiple designs over the years and there were also red fire alarm boxes, too, that allowed anyone to call in an emergency with a little click. Each fire alarm box, when activated, would transmit to firehouses a code that, when matched to a specific card in a file, would identify the location of the box and the companies expected to respond.

For a time there were also combo police and fire boxes.

At one time there were more than 2,500 call boxes dotted around the city, hard-wired into a network of cables that covered more than 500 miles.

"In some locations the boxes are still used by the police," says City of Milwaukee Department of Public Works’ Electrical Services Manager Bryan Pawlak, who works in the Infrastructure Services Division of Transportation Operations-Electrical Services, Communications.

But, Pawlak says that rumors that the disused boxes sometimes serve other functions, involving streetlights or traffic signals, are untrue.

Now that the system is mostly non-functional there are fewer and fewer boxes on the street every year.

"Theft and damages are a problem," says Pawlak, who adds, "I don’t have readily available data regarding a potential recent increase," when I note the seeming increase in social media posts about thefts.

In July 1992, the Journal reported that drivers had plowed into 28 call boxes already that year, noting that call boxes have been suffered all manner of vandalism for decades, including being cut down with saws, covered in graffiti, knocked over with cars and their locks jammed with chewing gum.

The city does remove some boxes, Pawlak says, but also works to main the existing ones.

"The City removes the boxes when they are damaged and in need of repair," he tells me.

"Sometimes they are removed when they are no longer in service or when we do not have spare parts for repairs. Whenever possible we make use of existing parts from other out-of-commission boxes. They are very labor intensive."

The boxes trace their roots in Milwaukee to the late 19th century.

While a 1992 Milwaukee Journal article notes that the red fire alarm boxes date back to 1868, and green police ones followed 30 years later, Manager of Central Drafting & Records at City of Milwaukee Yance Marti reminds us that before the police boxes were police "pagoda" boxes – like one you can see at Milwaukee Public Museum’s "Streets of Old Milwaukee."

Rather than call boxes, these were tall slender booths in which beat cops could stand at the ready, with access to a telegraph. Marti believes these came on the scene in the early 1880s and endured until about 900 of the later, phone-equipped boxes appeared around the turn of the century.

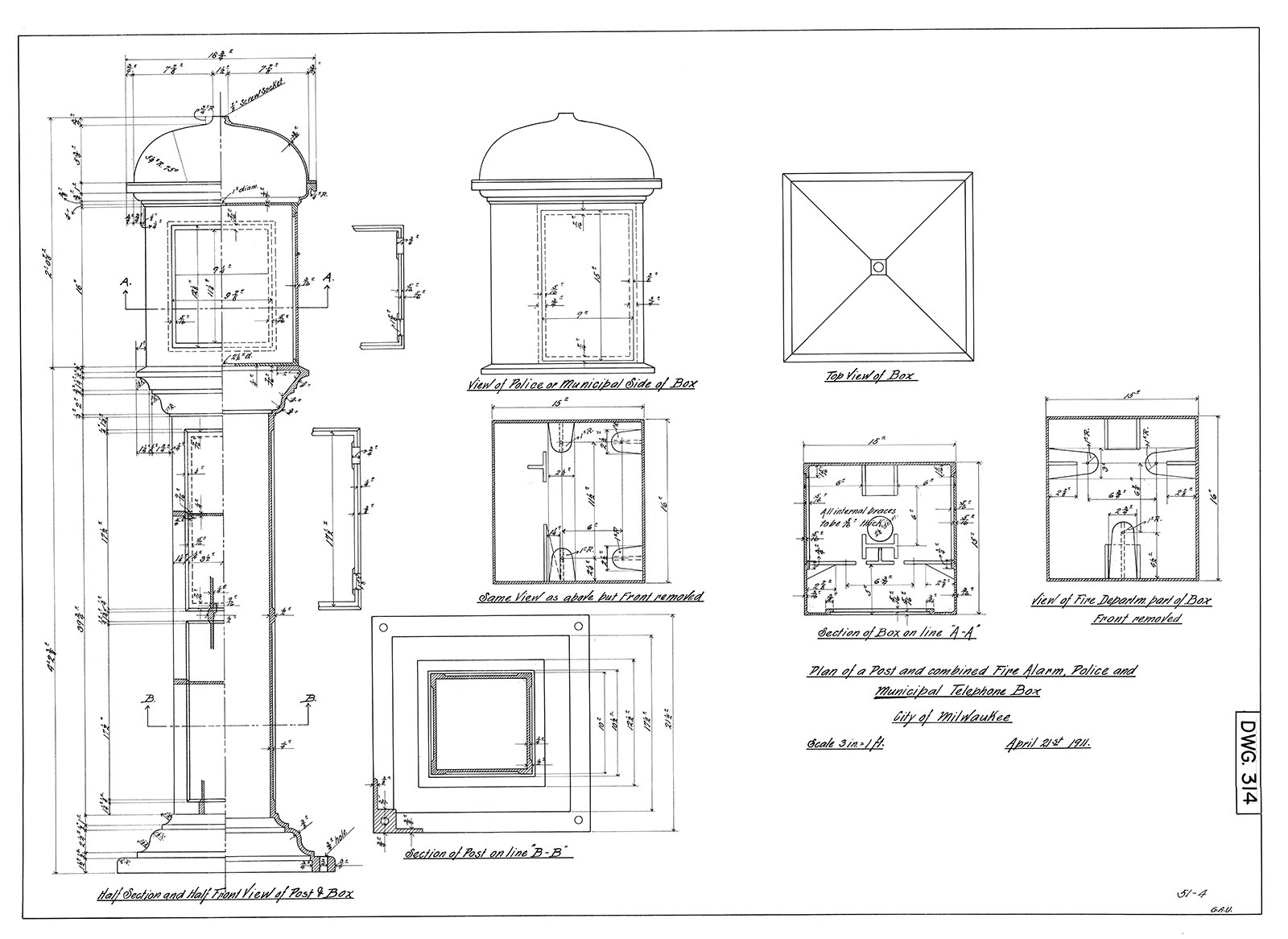

The police and fire systems were joined together in 1911, according to the Journal, and after World War II, slimmer, more modern-looking aluminum boxes began to appear.

But those aren’t the ones we love.

Instead, the hulking, yet ornate, boxes that have long since been painted blue date to the second decade of the 20th century, when they were designed by Oscar Kleinstuber, who patented the design.

Kleinsteuber was part of a respected Brew City family. His father Charles operated a machine shop on the site of the Journal Sentinel building at 3rd and State Streets. In his shop he cast some of the parts used by his neighbor Christopher Latham Sholes in his groundbreaking typewriter design.

Oscar worked for years as the city’s assistant superintendent of fire alarms, while his brother Monroe held the same post for police alarms and their brother Hugo was Monroe’s assistant.

But lest you think Hugo lived in his brothers’ shadows, consider that he is credited with one of the very first automatic traffic signals in the country, which was installed at 16th and Wisconsin.

Oscar, was promoted to supervisor of the combined police and fire alarm system in 1913 and, with Hugo’s help, set about designing new boxes. The design was patented in 1915, and 105 years later, his boxes can still be seen around Milwaukee today.

Though the little balls at the top no longer light up to alert officers of an incoming call, the look of the boxes changed little over the decades, and these sturdy classics remained on the scene even when slimmer iron boxes and, later, the sleeker but more workaday aluminum ones arrived.

Initially, the Kleinstuber Combination Post Company manufactured these vintage boxes. By 1920, the Fire and Police Alarm Post Company opened its factory at 45th and Mitchell Streets. Over the years, boxes were made by other companies, too, including Chicago’s Federal Electric Company and Milwaukee Malleable & Grey Iron Works.

While most of those later versions are long gone, somewhere in the neighborhood of 1,200 older boxes are still on the scene delighting those of us that love them.

The fire boxes didn’t endure.

Unlike police call boxes, the public had access to the fire alarm on those boxes, which made sense so that fires could be reported.

But false alarms cost precious resources, like time and money, and could be deadly if they prevented firefighters responding to real emergencies.

What's inside... (PHOTOS: Milwaukee Department of Public Works)

"About 95% of culprits are escaping scot free," Fire Chief Richard Seelen told the Journal in 1986, "and we have no way to apprehend them."

The paper reported that 10,962 false alarms were pulled from boxes in 1985, costing the city $283,806. Plus the annual maintenance on the boxes cost $69,235, with another $15,285 spent to repair them.

"The boxes have considerable historic value and have been in demand by collectors and history buff in cities where the box alarm system has been dismantled. Another possibility is to rent the underground cable system," Seelen told the paper.

In 1986, of 11,515 alarms pulled at fire boxes around the city, a whopping 10,402 were false alarms.

In November 1986, the City’s Finance and Personnel Committee approved spending $129,856 to take out 752 fire call boxes and another 227 combination fire and police boxes. The goal was to get rid of all 2,500 by the end of 1988.

They were gone by spring 1987 and replaced by the 9-1-1 telephone system.

More than 30 years later, we’re fortunate to still have police call boxes on the landscape. And, says DPW’s Pawlak, they’re not going anywhere for now.

"As we recognize the historic and aesthetic value of these call boxes," he says, "the City attempts to preserve as many of them as possible."

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has be heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.