This series originally ran in April 2016 for Milwaukee Day, but in honor of Milwaukee's birthday, we're re-running it to highlight the 21 people, moments and ideas that have defined Milwaukee and continue to shape the city. This is part 3 of 4. Happy birthday, MKE! Read Part 1 and Part 2.

11. Bay View Massacre: 1886

Also known as the Bay View Tragedy, the Bay View Massacre started on May 1, 1886, when 7,000 building-trades workers joined with 5,000 Polish laborers to go on strike against their employers in demand of an eight-hour work day. Within two days, 14,000 workers had joined forces in solidarity, gathering at the Milwaukee Iron Company rolling mill in Bay View (located at Russell and Superior on Jones Island).

The workers and their families, including children, camped in the nearby fields, and on May 4, the Kosciuszko Militia arrived. When the crowd approached the mill, they were fired upon and seven people died, including a 13-year-old boy. Since 1986, members of the Bay View Historical Society, the Wisconsin Labor History Society and other community groups have held a commemorative event to honor the memories of those killed during the incident.

12. Golda Meir in Milwaukee: 1906-1921

Golda Meir – teacher, stateswoman, politician and the fourth Prime Minister of Israel – was born in Kiev, Russian Empire (present-day Ukraine) in 1898. She later moved to Milwaukee with her family, where they operated a grocery store on the city’s North Side.

Meir attended the Fourth Street School – now Golda Meir School – from 1906 to 1912. During this time, she organized a fundraiser to pay for her classmates' textbooks and graduated as valedictorian of her class. She went on to graduate from Milwaukee’s North Division High School and later Milwaukee State Normal School (now University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee). After graduating with a teaching degree, she taught in Milwaukee public schools.

Meir later moved to a kibbutz in Palestine in 1921, with her husband, Morris Meyerson.

In 1967, Meir was elected Prime Minister of Israel, after serving as Minister of Labor and Foreign Minister. Meir was the world's fourth – and Israel’s first and only – woman to hold the office. Former Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion used to call Meir "the best man in the government." She passed away from lymphoma in 1978.

13. Milwaukee's socialist era and the creation of the parks: 1910

Emil Seidel was the first Socialist in the nation to be elected as mayor of a major city in 1910 after serving two terms as a Milwaukee city alderman. According to the Wisconsin Historical Society, he and his compatriots were dubbed sewer socialists, due to their back-to-the-basics strategies.

Seidel once said, "We wanted our workers to have pure air, we wanted them to have sunshine, we wanted planned homes, we wanted them to have living wages, we wanted recreation for young and old, we wanted vocational education, we wanted a chance for every human being to be strong and live a life of happiness. And we wanted everything that was necessary to give them that playgrounds, parks, lakes, beaches, clean creeks and rivers, swimming and wading pools, social centers, reading rooms, clean fun, music, dance, song and joy for all."

During his time in administration (one two-year term) Seidel brought about the first public works department, and Milwaukee's city parks system came to fruition. Once known as the Metropolitan Park Authority, the Milwaukee County Park System today boasts over 140 parks totaling nearly 15,000 acres that make our city and brighter and better place.

More socialist leaders followed Seidel's term, including Victor Berger (the first Socialist congressman), Daniel Hoan (mayor), and Frank Paul Zeidler (mayor). Milwaukee's Socialist era came to an end in 1960 with the election of Henry W. Maier, a Democrat.

14. The creation and destruction of Bronzeville: 1900-1950s

As black Americans headed north seeking employment, most settled along Walnut Street, which became known as Bronzeville. It became the primary location for many black-owned businesses, including barbershops, restaurants, taverns, exotic nightclubs and social clubs. And because it catered to racially mixed clientele who were looking for "exotic" entertainment, it brought in significant outside dollars to the depressed, discriminated economy. Some remember it as a place where people could sleep out on the porch when the nights were hot, and nobody locked their doors.

But during the late '50s and early '60s, a large portion of the neighborhood was destroyed and community members were displaced to make room for the I-43 expressway which cut directly through the center of the neighborhood. With the additional collapse of the industrial economy, the area never recovered. Currently there is an effort being made to redevelop the neighborhood along North Avenue's business district in an attempt to resurrect its dormant spirit.

15. Defining boundaries, inside and out: 1955

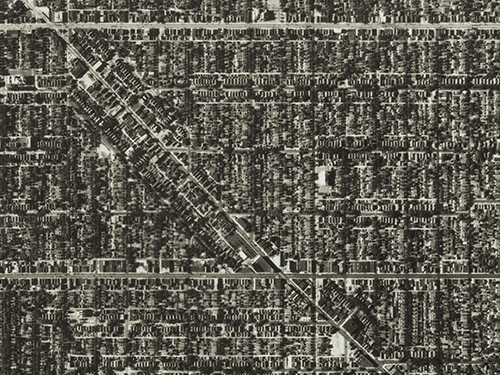

The city's internal boundaries were strongly refined and reinforced because of the routing of Milwaukee's freeway system, which was often used as an excuse to destroy struggling neighborhoods and divide communities. According to the U.S. transportation secretary, Anthony Foxx, "We now know — overwhelmingly — that our urban freeways were almost always routed through low-income and minority neighborhoods, creating disconnections from opportunity that exist to this day." According to research by Raymond A. Mohl for the Poverty and Race Research Action Council, "In Milwaukee, the North-South Expressway cleared a path through sixteen blocks in the city's black community, uprooting 600 families and ultimately intensifying patterns of racial segregation." Even today, the effect of freeways through the city occasionally bubble up with freeway takeovers being a highly visible part of current protests.

The density and community of Bronzeville was destroyed as the city took vast swaths of land to develop the freeway system. The area is just now starting to bounce back. Click the images to enlarge.

While roads defined the interior, annexation was responsible for growing the city limits. Perhaps more importantly, it was part of growing the city's tax base. The Village of Bay View, the Town of Lake and the Town of Milwaukee were among the earliest acquisitions in 1887, and parts of the town of Granville were among the later acquisitions in 1955 (though the official boundaries between Milwaukee's share and what eventually became known as Brown Deer were not made official until 1962).

The potential for annexation was far reaching, particularly in the '40s and '50s during Frank Zeidler's mayoral leadership, even going out as far as the city of Waukesha. Through Zeidler's efforts, the city's area doubled in size, but many outlying communities wanted to disassociate themselves from Milwaukee's poverty and resisted becoming a part of the city. Annexation of limited portions of land, such as the annexation of the town of Greenfield, created odd city borders where the city appears to leak around unacquired cities. Milwaukee also incorporated the town of North Milwaukee; West Milwaukee and South Milwaukee remain.

Milwaukee also annexed small portions of the Town of Oak Creek and the Town of Wauwatosa.

But while Milwaukee's external boundaries now remain mostly static, the internal boundaries are constantly in flux. The destruction of the Park East Freeway, the recent debate about saving or scrapping the Hoan Bridge, and the newly developing lakefront gateway and neighborhood bonding efforts such as Connect 53212 all offer opportunities for the city to redefine, separate or galvanize the community.

Part 4 - Civil rights, Summerfest, sculptures, schools and sports