Though not quite at the dizzying rates that once made it the best-selling beer in the country, the "beer that made Milwaukee famous" is quickly becoming a favorite again.

It's been a little over a year since the reformulated "classic" Schlitz returned to the market and its popularity thus far has exceeded expectations.

"The response has been overwhelming," says Kyle Wortham, senior brand manager for Schlitz.

Bringing back the iconic brew was a risky venture, especially in a marketplace dominated by heavyweights Miller and Budweiser and the ever-growing demand for microbrews. Still, the company felt that it was a risk worth taking.

"We would get letters and calls all the time from people who loved the brand," Worthington says. "A lot of people talked about remembering a more simple time and how the big brews don't taste like they used to.

"Schlitz was the No. 1 beer in the world. That was the inspiration behind it, in a market void of flavor in a mass-brewed beer, we wanted to find the formula and give it back."

With that, research began. And it was no easy task. The recipe wasn't stored in a long-forgotten filing cabinet and the team set out to track down old brewery workers, brewmasters and others familiar with the product.

Brewmaster Bob Newman put together a number of sample batches, based on the gathered information and, finally came up with a finished product. When he did, it won the approval of the old-timers.

"They validated it and gave it their seal of approval," Worthman says. "It was as close as we could get without the written formula."

With the recipe perfected, it was time to launch. The company focused on the Midwest, where Schlitz established its roots during the early part of the 20th century; Chicago, Milwaukee and Minneapolis were among the first. When the beer came to Milwaukee, shopkeepers couldn't keep it on the shelves.

Some stores had waiting lists for the beer and sold out before inventory would arrive. Eventually, production was transferred to Milwaukee -- it had been being brewed at a Miller facility in North Carolina -- and supply is plentiful, and the beer is still selling strong.

"We never expected that," Wortham says. "We wanted to run before we walked. We're very happy. It was a good problem to have."

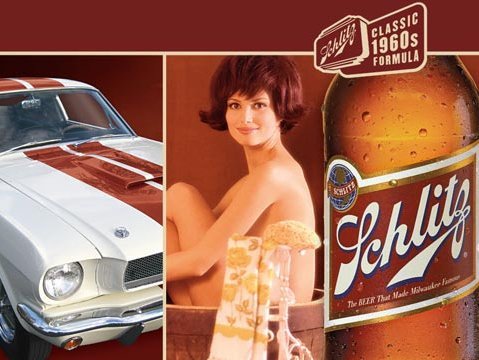

There was an advertising campaign, but -- at least by industry standards -- it was subdued. Instead of the non-stop advertising campaigns employed by the major brewers, Schlitz instead chose to employ a strategic marketing plan that played heavily on nostalgia.

"We don't need a special label that turns blue when the beer is cold or a special mouth for a wider pour," Wortham says. "This beer has a real identity. With 100 percent accuracy in this industry, you can predict a flash in the pan. Companies spend millions and flood the marketplace. We took the reverse approach; we started small and meaning full. Schlitz has very deep roots."

Schlitz was once the mightiest of Milwaukee's breweries and an innovator in the brewing industry.

But for the last three decades, until last summer's re-introduction, Schlitz was a "discount beer;" the kind that frat brothers picked up for a cheap night of binge-drinking. When it came back, the new-old beer was sold at a premium price point, comparable to big-label offerings like Miller Lite and Budweiser.

"This is a beer that shared shelf space with the brands from St. Louis and Milwaukee," Wortham says. "Unfortunately, it dropped in price. This beer and the way its brewed warrant the premium price."

The new-old Schlitz was released in its famous brown bottle; which the company originally introduced in 1912 in order to prevent light from spoiling the beer. With the exception of Miller High Life, most brewers now sell beer in brown bottles. Bringing back the familiar packaging, Worthman says, was a key component of the plan.

The formula recreates a flavor that was once one of the best-selling beers in the United States and the trademark of one of the city's biggest corporate legacies.

Joseph Schlitz was just 20 years old when he came to Milwaukee from Mainz, Germany. He got his start by working as a bookkeeper in August Krug's brewery and took over the company following Krug's death in 1856. Just two years later, Schlitz married Krug's wife, and changed the name of the brewery to the Joseph Schlitz Brewing Company.

Schlitz was one of a handful of breweries in Milwaukee during the early years, but expanded its market after the 1871 Great Chicago Fire. Schlitz quickly sent thousands of barrels across the state line to Chicago, which lost most of its own breweries in the blaze. As the city rebuilt, Schlitz opened a distributorship in the city, and the brand grew quickly thereafter.

The company continued to grow, even after Schlitz's death in an 1875 shipwreck. By the early part of the 20th Century, Schlitz was producing a million barrels a year. In 1903, Schlitz surpassed its crosstown rival, Pabst, to become the No. 1 selling beer in the United States, a position the company held until the onset of prohibition.

When the federal ban on booze went into effect, Schlitz stayed afloat by producing non-alcoholic items, including a line of chocolates. Once the ban was lifted, the brewery was one of the first in town to resume production. Quickly, the company regained its position as the country's top seller and would stay there until a 1953 strike -- that effectively closed all of Milwaukee's breweries during the summer -- allowed Anheuser-Busch to take over at the top.

"All the breweries in Milwaukee closed down because of that strike," says Leonard Jurgenson, an unofficial historian of Schlitz. "When you close down in the summer months, your closest competition steps in and Anheuser-Busch became No. 1."

After the strike, Schlitz briefly regained the top spot in sales but fell back to No. 2 again and stayed there until the 1970s, when things began to unravel for the giant. The company was operating 11 breweries and none were operating at capacity. Schlitz was paying more for barley and other costs were going up.

To save money, the company changed the brewing process, but that led to flat beer that wouldn't keep a head. To counteract that, Schlitz added a seaweed extract. But when left in the bottle for a few weeks, the additive solidified, leading to "floaters" in the beer.

"All of that killed the market," Jurgenson says. "Schlitz never recovered from that."

A workers' strike in 1981 was the final nail in the coffin for the once-mighty brewer, and Detroit-based Stroh bought Schlitz a year later. Stroh closed the Milwaukee facility, ending more than a century of tradition.

Aside from being a titan of the brewing industry, Schlitz also had a major presence in Milwaukee. The Uihlein family was a major benefactor in the community and you could find somebody employed by Schlitz on just about every block of the city.

"In the ‘50s and ‘60s, you either had a relative or friend working at the brewery," Jurgenson says. "Everybody knew somebody that worked at the brewery. It touched everybody. Not just beer; distribution, all the things that go with it."

The fabled Schlitz Hotel and Palm Garden were among the hottest spots in town during their heyday. The Uihleins also sponsored the first years of the original Great Circus Parade, complete with the fabled 40-horse hitch pulling the Schlitz Bandwagon.

The beer was big in town. Sure, Miller and Pabst had a presence but Schlitz was king.

"We served it at my wedding," Jurgenson says. "If you were having an event, a wedding or something big, it was expected you would have Schlitz."

The Uihlein family ran the company until the end and treated its employees like members of the family. The owners knew employees by name and everybody was treated as an equal, whether they were executives or on the maintenance staff.

"That was the important thing," Jurgenson said. "The Uihleins took very good care of their employees; they appreciated them."

In an odd twist of fate, Pabst -- once itself a titan on the Milwaukee brewing scene -- bought the Schlitz brand from Stroh in 1999. Now a brewery in name only, Pabst contracts with Miller to brew the beer.

The former brewery complex, located just north of the old Park East Corridor, was reconfigured into the "Schlitz Park" office complex. When Schlitz made its return a year ago, a kick-off event was held at Libiamo, formerly the Brown Bottle Pub, in what's left of the old facility.

Not long after its reintroduction, production was transferred to Miller's Milwaukee brewery. The decision made financial sense, considering the brand's popularity in Milwaukee and the Midwest, but it was more of a nostalgic call for the company.

"It wasn't so much business but more of it makes sense," Wortham says. "That was more an emotional decision as opposed to profits."

With the beer being brewed again in Milwaukee, things have come full circle. Schlitz is no longer the king of the industry, but it is returning to its Milwaukee roots and another generation of beer-drinkers are experiencing what their fathers and grandfathers did before.

A year after its launch, Schlitz is selling well and exceeding original estimates and projections by over 100 percent. Not long after the bottles were launched, the draft version became available in Milwaukee bars and has also sold well.

"I'll be the first to admit that I was naive," Wortham says. "It's good to hear folks say this is a real beer. This wasn't about finding the new drinkers; we wanted to bring it back to folks that remembered it the most."

For now, Schlitz will remain available in select markets. After Milwaukee, it was reintroduced in Madison and La Crosse and recently became available in Oshkosh, Appleton and the Fox Valley. As of now, there are no plans to expand nationally, but that could change.

"If demand gets there, sure," Wortham says. "But we're happy where we are right now."