Let us remember stained glass painter Maria Herndl at her happiest moment. The artist deserves to be better remembered than she is – more than just a footnote or entry with a scattering of old newspaper clippings.

We find Marie (as she liked to be called) at her most victorious in front of a stained glass painting first titled "Queen of the Elves," or as it was later known, "The Fairy Queen." She has many other impressive works bearing her name and a couple than can still be viewed. But this beautiful 6-x-9-foot piece of mystery and controversy spends most of its existence in a basement, forgotten and unclaimed.

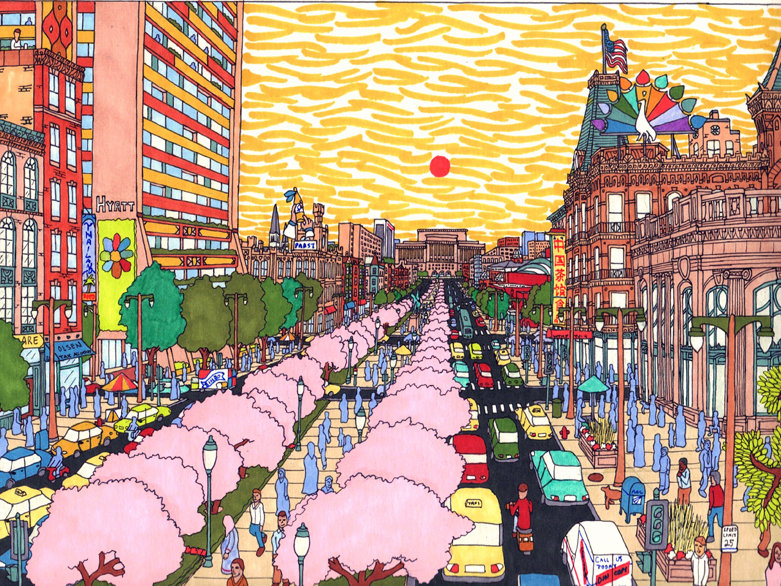

We look in on Marie at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago, also known as the World’s Fair. She is being handed a bronze medal for this work and several diplomas. "The Fairy Queen" has now been seen by thousands of people from around the world and, in the next year, will hold a special place in the Field House in Chicago. Years after that, it will be featured at the Exposition Art Gallery Building in Milwaukee.

Marie Herndl

As a girl in Munich, Marie was the daughter of teachers and showed artistic talent early on. She is allowed into the Royal Art Institute, where, in the advanced classes, she was the sole woman under the tutelage of school director F.X. Zettler. He only lets her in his prestigious stained glass courses after creating a partition so the other male students would never be distracted by her.

Herndl then apprenticed with Gabriel Meyer Studio, and her first major sale is said to be "Brunhilde at Worms," which goes to a prominent Bavarian castle. She also contributed to a painting of King Ludwig I of Bavaria. By this point, she may have already created "The Fairy Queen," which is seen to contain her name and city of artist origin. However, it was uncommon for stained glass artists to sign their work. Marie Herndl may have picked up that point of pride from one of her next employers in America.

Marie states in one article that she worked in New York for famed stained glass art masters John LaFarge and then Louis C. Tiffany. Even without documentation, this latter claim is likely. The famed studio head Tiffany often employed single women (if you got married you got fired) and in 1892 even hired more women after the male glasscutters union went on strike. One of these off and on-again female workers named Clara Driscoll has now been cited as guiding the women, and likely designed and created some of the most famous pieces for Tiffany’s studio, with the namesake taking the credit.

All the work records were intentionally destroyed in 1930, and the studio later died with Tiffany, so we’ll never know for sure if Herndl was part of this workforce.

What is known is that LaFarge and Tiffany published countering essays upset with the organizers of the 1893 Columbian Expo for not having a dedicated space in the Palace of Fine Arts Building to stained glass art. Tiffany stubbornly sets up an exhibit elsewhere on the Midway. Herndl’s success must have felt vindicating for her if they crossed paths.

When she was still in New York, Herndl was responsible for several works for prominent families. Some are like "Sword Dancer" and several poet windows created for the opulent music room of infamous railroad executive, lawyer and Republican Representative Edward Lauterbach. They may have been lost in a nasty divorce and the demolition of the Fifth Avenue and 78th Street townhouse in 1923.

"Good Shepherd"

In 1893, "The Fairy Queen" is installed in the Woman’s Building at the World’s Fair. It is a deeply colorful, lithe and contemplative piece. Former Smith Museum curator and college professor Rolf Achilles is one of the last people to have spent any great amount of time examining the piece and notes that "the painting on the glass is very thick like a canvas, not in the Mayer of Munich Style ... and quite different than Tiffany's Studio, too. She was her own artist."

Herndl told one reporter that the initial sketches were made from her sister and seven friends as models. It is a nighttime scene at the pond’s edge in the wooded grove. The central crowned figure is accentuated with a halo of light. She is surrounded by winsome handmaidens. They are natural and nude except for a strategic length of sheer cloth covering lower nether regions.

It is this bare nature that causes 75 years of woes for "The Fairy Queen." After the window was placed and cataloged in the Expo guide, Herndl was approached by Mrs. Candace Wheeler, one of the lead directors of the Woman’s Building – which was a sort of compendium of all the other Theme, State and World buildings in "the White City". It expounded the achievements and skills of women while also segregating all of them from the men.

"That is not a proper picture," Mrs. Wheeler lectured her. "It may go in Germany, but it won’t do for the Woman’s Building at the World’s Fair. If you insist on exhibiting it, you will have to give that central figure a decent dress … Whitewash her, paint her, anything, but you must cover her from the knees to the throat. We don’t mind the other figures but that central one must be dressed."

"The Fairy Queen"

Marie Herndl refused quite forcibly. This story got into the newspapers, and managers took action. The artist returned to find her piece moved to the Afro-American women’s exhibit and facing the wrong side out.

This was meant to be a double insult; with the exception of the Haiti Building, there were limited exhibitions dedicated to the accomplishments of darker-skinned people of the day. Organizers reasoned that it was too soon after slavery was abolished to be fair to anyone in the black community. Frederick Douglass campaigned to lecture at the World’s Fair but was turned down. Many of the exhibit halls contained exhibits showing the world’s people in primitive and cartoonishly racist ways (even for that time). Specifically speaking, the Afro-American women’s exhibit was meant to be a diminished, intentionally out-of-the-way place.

Herndl somehow negotiated with the exhibitors of the Electric Building to have the "Queen of the Elves" moved there.

This turned out to be one of the most popular places at the Expo both with daytime and evening audiences. Here, Edison and Westinghouse and Tesla were vying for attention with advances in incandescent bulbs and AC current technology. The stained glass painting took prominent display and won two medals and a certificate from the well-known Russian juror Professor Krupsky.

Jumping ahead to 1899, Maria Herndl was lured to the German Athens known as Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Commissions were already awaiting there. This was relatively the same calling as taken by fellow Munich resident and Expo artist Cyril Colnik, best known for his studio’s architectural ironworks in Milwaukee and whose artifacts can still be seen at the Villa Terrace museum along the lakefront.

Herndl should have been as famous as Colnik, but had some factors working against her. Herndl was a persistent, single woman who spoke in broken English. She preferred the company of her cats and worked in "a bohemian confusion" studio. She not only designed her windows but also assisted in most of the labor firing the glass and foiling the windows into shape. She stated that she would insist on re-firing the glass panels over and over until it was right. Her first studio and team worked on Mitchell Street, but she would move shop and separate residence several times in the next decade.

One time, she successfully counter-sued a Downtown landlord who rented her a second-floor studio on North Milwaukee Street. The landlord proceeded to let an early automobile factory move in downstairs, and the vibrations were so terrible that it was not suitable for a stained glass creation space. Herndl paid to the end of December but abandoned the space. When the landlord sued, the artist countered and won in court. She was not a person to take advantage.

Unlike Colnik, there is no catalog of Herndl’s work or documents archived. Most of the information here is generated from brief news articles and probate records. It is known that she created works for St. Louis patrons and churches while she attended the 1904 World’s Fair to display two personal works, "Hans Christian Andersen" and "George Washington."

One of her smaller St. Louis windows is currently for sale on eBay. It is a 21x25-inch portrait window called "Flight into Egypt" which was pulled from a demolished Catholic girls’ primary school. The current asking price is $19,500.

Marie Herndl wrote President Theodore Roosevelt and suggested that while they were both in St. Louis for the World’s Fair, she would like to paint his portrait. Somehow, Marie thought that was enough and approached the private residence Roosevelt was staying. She was promptly arrested by the Secret Service as a crank. After the dust had settled, apologies were made, and supposedly a session was indeed held. Herndl’s windows at the Fair later won awards and can still be found.

"Hans Christian Andersen" was bought by 100 individual art patrons and donated to the Central Public Library in Milwaukee. It is Herndl’s second most touching work and can be seen in the southern window of the Children’s Room there. An examination of the detail reveals gnomes and translucent fairies.

"George Washington"

The other window, "George Washington," shows the future President astride his horse while General Steuben and LaFayette advise him. Herndl sent countless letters urging the government to install it in the U.S. Capitol. They finally relented and even invited her to create two circular skylights featuring seals of the original 13 colonies. While some accounts say these seals exist, it is unknown if she ever finished this work in the year she died.

The Washington window is currently in a cafeteria-like chamber of the Senate, last publicly noted as needing repair after a 1971 bomb attack at the U.S. Capitol caused some of the window’s faces to fall out. The skylights may be in the Senate Press Room, but no images of them can be found.

During her early period (1899-1902) in Milwaukee, Herndl created six windows for the Christ King chapel at the St. Francis de Sales seminary. This was during a time when the area was still unnamed and not surrounded by much. Her connection to the project, aside from the Germanic founding priests and the heavily Germanic parish, may have been the great art patron King Ludwig I of Bavaria once again, who gave the seminary things like front doors and a chandelier from his own castle.

Christ King chapel at the St. Francis de Sales seminary

The six stained glass windows themselves are definitely Herndl’s with delicate detail, vibrant color, deep perspectives and original composition. In the corner of one window is a beehive, an early symbol of the Catholic Church as example for how to live (chaste and devoted to work), eloquently and with a sense of togetherness. Another window has gothic script containing the names of the window’s patrons, and another has Marie Herndl’s big font signature at the bottom.

Among the lost artifacts from the Milwaukee years is a series of windows commissioned by Patrick Cudahy in 1911 as a secondary wedding present for his daughter Elizabeth and son-in-law August J. Beck. The primary gift was a very gothic looking house he bought just a few doors down from Villa Terrace. Herndl’s staircase windows reportedly depicted the seasons with Cudahy’s children playing in them. The house itself has since changed hands and remains in a separate family’s trust, but it is likely the windows did not remain there.

"The Fairy Queen" had a fabulous early life, but by 1909, Marie Herndl was fervent to sell it to the Milwaukee Auditorium (now Theatre) which was just opening. She tried again the next year with an asking price of $1,650 – roughly $40,000 in today’s market. They refused on the grounds that the nudity might harm the well-being of children attending events. In 1911, public subscription was being raised to install it in Plankinton Hall in the Auditorium for $1,800. Nothing transpired.

Then, one day in 1912, it supposedly landed on the Auditorium’s doorstep unannounced and without a home. The board again decided they could not show it and placed it in the infamous hell of basement storage. For a time, it would have shared space with a sister art piece, the infamous missing Germania statue. "The Fairy Queen" would outlive Germania – languishing in storage for 47 years.

The timing is not clear on this, but the window may have landed with the Auditorium after Marie Herndl’s death on May 13, 1912. Newspapers noting her passing reported she died at her home and did not give a cause. The death certificate and probate records at the Milwaukee Courthouse reveal a different story.

Early in 1912, Marie saw a doctor almost every day in pain and very feeling constipated. When she was admitted to St. Joseph’s Hospital in late April, a doctor told her that there was a malignant tumor in her colon (likely in modern terms an advanced case of colitis and perhaps colorectal cancer). It was at her bedside that her will was made with an appointed lawyer. During a second laparotomy surgery in 15 days, Marie Herndl died of shock.

Her official will lists an inventory made of all worldly possessions worth turning into liquidity. The medals and diplomas were listed among the furniture but deemed worthless. Herndl specifically leaves them to a friend named Feffie Hand Martin. What records do not show is what became of any artwork or stained glass tools not at her home. If she still kept a separate art studio, it was not included in the ledgers.

The funeral and burial at Holy Cross Cemetery was attended by a handful of nuns from the hospital, and Herndl’s will left funds to just a few friends with the rest ($1,200 after bills were paid and death taxes taken – roughly $29,000 in today’s dollars) going to the city’s "worthy poor." Two estranged cousins learned of her death and tried to get their share, but the money had already been distributed to several single mothers whose husbands ran out on them.

In 1959, "The Fairy Queen" was brought out for a special party at the Milwaukee Auditorium’s 50th anniversary. Its presence made all the papers, and again the board nervously shelved it. The Milwaukee Press Club considered buying it, but then gave up.

In 1967, a cash-strapped board asked the director of the Milwaukee Art Center (soon to become the Milwaukee Art Museum) Tracy Atkinson for an assessment and inclusion in the Center’s collection. In a rather droll account by Jay Joslyn in the Milwaukee Sentinel, Atkinson decreed, "These are not nudes – they are naked women."

Atkinson advised the Auditorium Board that there was a market for such things on the East Coast and that they should photograph it for circulation to dealers. Instead, an aspiring local nightclub owner and river environmentalist named Tom Terres came to the rescue.

Terres purchased "The Fairy Queen" to be the crown jewel at a riverboat restaurant and adjoining 10-story hotel on the Milwaukee River – right above the dam and across from what is still known as Caesar’s Pool. But Terres appears to have struggled in financing such a venture, fighting re-zoning measures and cleaning up the dirty riverbank. He settled for building a concrete restaurant in the shape of a riverboat with a second floor apartment where he could live out his retirement.

"The Fairy Queen" was indeed committed to the main window of the jazz-filled restaurant mostly known as the Riverboat Cocktail Lounge for the next 35 years. It changed hands and names a few times before the last incarnation known as Melanec’s Wheelhouse. As progress marched towards that area of the Milwaukee River in the mid-2000s, the last operator sold the property, and the Wheelhouse was razed as a clean-up effort and a return to nature.

The glass painting was seemingly forgotten again, but in fact, it had been donated to the Chicago Historical Museum. The CHM in turn loaned the work to the Smith Museum of Stained Glass Windows at Navy Pier. This is where our one good image comes from, as photographed by Rolf Achilles.

The unconventional Smith Museum space had a long run that ignominiously ended when Navy Pier decided to make renovations for more commercial interests. In 2014, "Fairy Queen" was carefully conserved into a crate and currently rests in a storage facility in Chicago. There are no current plans for the artwork to be brought out into the light.

The one good portrait we have of Marie Herndl comes from the 1899 Milwaukee Sentinel, on file at the Milwaukee Public Library who kept clippings to research the Andersen window.

Marie states, "You can get color on canvas, oh yes. But never such color as you can get on glass, for even a dull color takes on wonderful tones when you have it with the sun shining through. And there is always the joy of getting some richer and deeper tone in the painting or the firing and then the joy of blending all these into a great picture which will never grow dim."

In one last article from 1911, Marie said, "For a long time, I had a hard time; the ways of the artist are not always bright nor is the work as easy as some imagine. If I had a daughter, I would not advise her to take up the work. The work is so hard that unless one is determined and diligent as well as in love with it, failure is certain."