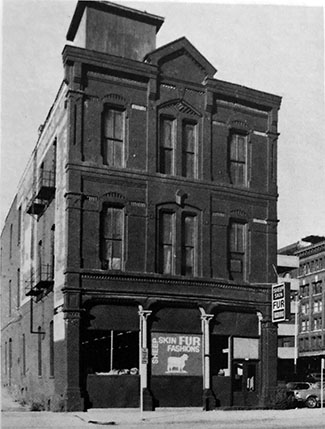

One of the older buildings in Downtown Milwaukee has stood sentinel at 320 E. Clybourn Ave. for nearly 150 years, weathering good times and bad, as buildings have come and gone around it, leaving it the only thing on its square block, aside from a parking ramp.

Across the street, an entire block was erased by the I-794 freeway spur that slices between Downtown and the Third Ward.

Now, the three-story Italianate cream city brick commercial building – with striking brownstone details – designed by landmark Milwaukee architect Edward Townsend Mix and erected in 1874, is getting the attention it deserves.

The building will become home to the Central Standard Craft Distillery tasting room, bottle shop and innovation distillery with a 100-gallon pot still, as well as an events space and a floor of office space for lease ... making it one of the loveliest urban distillery buildings anywhere, along with Michter's Fort Nelson distillery in downtown Louisville.

Though the structure was occupied for most of its life, in recent years it fell vacant, its future seemingly more questionable with each passing year.

"We started looking about a year ago and for us, it was just finding the right spot," says Evan Hughes, co-owner (with Pat McQuillan) of Central Standard, which is moving because its current building in Walker’s Point was recently sold for a new Adventure Rock climbing facility.

"This wasn't initially on our radar. We looked all over town, even outside in the suburbs. We did our due diligence and saw some really good stuff.

"We started understanding all the stuff coming up around here this year, and we were like, ‘all right, let's actually make the jump.’"

In addition to the new Huron office building across Broadway, there is a Kinn hotel getting underway on the corner of Broadway and Michigan, plus, says Hughes, new hotels just about everywhere nearby, from the Springhill Suites to the Hilton Garden Inn to the Westin to the Cambria to two new hotels under construction a block east.

The Historic Milwaukee Inc. retail shop and walking tours headquarters is also located nearby.

Central Standard owners Pat McQuillan and Evan Hughes.

"So much of our business is tourism and there’s so much here. The neighborhood's very vibrant, we love that the Huron building's going up, there's a restaurant in the first floor. We love being kind of at that crossroads of Downtown."

While the location is perfect (Central Standard’s production and aging facility is further west along Clybourn Avenue ... so, maybe there’ll be a Clybourn Avenue Single Malt someday), Hughes, who has a passion for history, loves the building itself, too, and has already been digging into its history.

"We walked in, and you could imagine it," he says as we stand in the wide open first floor. "When the door opened on this building, we walked in and just felt it. We were like, ‘this is it.’ There’s no better place."

That must’ve been how Edward Townsend Mix felt, too.

Born in New Haven, Connecticut in 1831, Mix moved to Andover, Illinois with his family five years later, before moving again when he was 14, this time to New York City, where he studied architecture with Sidney Mason Stone and Richard Upjohn.

In 1855, Mix went to Chicago and partnered with William W. Boyington, but soon after, he decided to strike out on his own and to do so in Milwaukee, where he joined a very small cadre of formally trained architects. Within eight years, he was appointed State Architect, serving for three years.

By this time, Mix was the fashionable choice to design mansions for Milwaukee’s elite, churches for its congregations and civic structures like the National Soldiers Home – where his Gothic Revival Old Main is currently being renovated into veterans housing – the sadly demolished Everett Street Depot for the Milwaukee Road and public schools.

His work on the Mackie and Mitchell Buildings on Michigan Street between Broadway and Water is some of his most recognizable.

Mix was also in demand beyond Milwaukee and his works include the Kansas State Capitol in Topeka, Villa Louis in Prairie du Chien and Montauk in Clermont, Iowa for that state’s Gov. William Larrabee.

When the Wisconsin Leather Company – founded by William Allen and Edward P. Allis (yes, that Allis) in 1846 as the Empire Leather Store – wanted to expand, it bought two lots on what was then Huron Street.

But in an interesting twist, and one hinted at by the fact that a stone near the gable of the building is inscribed with Mix’s name and the date 1874, it appears that Mix owned the building and rented it to Wisconsin Leather Company, which by then was one of the biggest tanneries in the country (and from which Allis had exited 20 years earlier).

In another interesting twist, according to the National Parks Service report prepared in 2004 as part of the process to add the building to the National Register of Historic Places the following year, "In 1874 Mix and his neighbor to the east agreed to build one wall on the line between their two properties and share it in perpetuity. This wall straddled the lot line, with half of its depth resting on either lot. The east side of this wall was not utilized until 1883, when Mix sold the half-thickness of the already erected wall to J.S. Richter for use as the west wall of a three-story structure."

While this sort of arrangement was not unheard of, what is notable is that long after that 1883 structure has been demolished (sometime in the 1970s, it seems), the west half of that shared wall can still be seen and resting at the foot of it along the sidewalk is the sole other remnant of the razed building: three rusticated stones stacked vertically with a carved stone element resting atop it (pictured at right).

"That came back on our survey," says Hughes with a chuckle, "and the surveyor was like, ‘you don't own that.’ Just leave it."

By the late 1880s, Wisconsin Leather Company was struggling financially and moved across Broadway to the new Loyalty Building (now home to the Hilton Garden Inn). Soon, the Clybourn building became home to the Charles L. Kiewert Co., a brewery outfitter that dabbled in other businesses, too.

Founded in 1870 as Kiewert and Ladwig, Kiewert Co. was, by 1892, dealing its brewery machinery, appliances and materials, including hops and malt and bottling line equipment, throughout the western United States.

Born in the Kashubia region of what is now Poland but was then West Prussia in 1846, Kiewert was the son of a mayor in the area and came to Milwaukee in 1862, where he studied law and was admitted to the bar in 1867. Soon after, he changed careers, becoming a traveling salesman for a few years before launching his brewery supply business.

In 1869 he married Amelia Geuder and they had three sons and one daughter.

Interestingly, Kiewert's brothers Emil and Robert were liquor dealers and distillers, having bought the Menomonee Valley Distillery in 1874.

In addition to the brewery supply trade, Charles Kiewert also seems to have been active in the kind of businesses he sold to.

In 1885 he was a partner in a malt extract company that bought the Muntzenberger brewery in Kenosha to produce New Era beer under license.

In Milwaukee, he leased the former Engelhardt Brewery building on Windlake Avenue, but doesn’t appear to have run it as a brewery. The same was true in 1900 in the Wisconsin Dells, where Kiewert purchased a brewery that had been damaged by fire but never got it back up and running.

Seven years previous, Kiewert partnered with maltster William Froedert and brewers Jacob Lutz and Theodore Knapstein to buy Twin City Brewing in Wisconsin Rapids after its founding partners went bankrupt.

Kiewert was a busy man. In 1898 he was re-appointed to the board of trustees of the city’s museum by Mayor David Rose. At the same time he served as president of the Milwaukee Musical Society and also of the influential Deutscher Club. He also appears to have been active in real estate, platting the Riverside subdivision in Watertown, where he also donated land that became Riverside Park in that city.

In 1909, his company – still occupying the Clybourn Street building – was advertising the sale of flaming arc lamps, which might be a business related to another one for which his company became known, this time thanks to his son Robert.

Robert W. Kiewert was, according to Robert Grau’s "The Stage in the Twentieth Century," "an important figure in the film industry, whose influence has extended into other fields ... having made a study of carbon conditions for many years, (he) affiliated himself with the great Berlin house, Gebrueder Siemens & Co., the largest carbon factory in the world. It was this same Mr. Kiewert who suggested to Herr Viertel, of Berlin (the technical director of Siemens & Co.), the new bio carbon, and the same was developed as a result of Mr. Kiewert’s operations. No one needs to be told what these bio carbons have meant in the progress of the moving picture."

This development was utilized by the Charles L. Kiewert Co. to manufacture lighting elements for motion picture projectors, boosting the nascent film industry.

This development was utilized by the Charles L. Kiewert Co. to manufacture lighting elements for motion picture projectors, boosting the nascent film industry.

A company brochure boasted, "the BIO Carbon is the only real improvement in projector carbons that has been made in the last 10 years, and is especially designed for the projection of motion pictures," adding that the Kiewert carbon burned longer, brighter and softer.

"That the Bio carbon will produce motion pictures at least 50 percent better than is otherwise possible is the opinion of all who have tried it, and it is the accepted standard of the best operators in the country."

When the elder Kiewert died in 1912 at the age 66, a newspaper obituary noted that he was involved in "many other small firms" besides the company that bore his name, but his passing spelled the demise of the company, which seems to have faded away in the years soon after.

By the dawn of the 1930s, the Clybourn Street building was home to Tindall, Kolbe and McDowell, which imported and sold coffee, tea and spices, including Imperial Brand coffee, packaged in special china containers.

By the dawn of the 1930s, the Clybourn Street building was home to Tindall, Kolbe and McDowell, which imported and sold coffee, tea and spices, including Imperial Brand coffee, packaged in special china containers.

A decade later, that company was leasing space to the General Merchandise Company, which manufactured and sold "novelties."

As World War II came to an end, Johnson Controls was using the building for storage and shipping, but by 1947, Stein’s Kosciuszko Furniture – headquartered on Lincoln Avenue – had a warehouse store there.

Though the furniture store changed names – it was also called Maxons for a time, as well as Whittings – it endured until the early 1960s, when the Weidig Display Studio moved there from 416 N. Milwaukee St. in order to expand its business designing and constructing custom displays.

From the early 1970s onward, the building housed Sheepskin Fur Fashions, another company whose name, but not its business, seems to have changed a bit over the years.

In the 1990s, White Thunder Wolf, a retail shop selling Native American objects, including clothing, occupied the first floor, and, after renovation work, including removing the exterior paint, it was replaced in 2001 by From Afar, in which owner Karen Hembrock sold furniture, artwork, crafts and other objects from around the globe.

Since that shop closed years ago, the building has apparently been vacant. But, thankfully, that’s about to change.

Hughes shows me the basement (above) first, despite the fact that other than installing a kitchen, it’s unclear what will happen down here. But it’s cool to peek into the space beneath the sidewalk and to see the astonishing stone foundation that appears as a solid as a ... well, you know.

Also interesting to note is that there were once much larger windows in the west wall, where there must have been light wells, or the grade was much lower (or both).

There’s also a remnant of what Hughes guesses was a fireplace down here (pictured below).

The three main floors are all quite similar, with windows in the front and west facades, and a row of heavy wood pillars running straight down the center. The floors tend to slope away from these toward the exterior walls and Hughes knows why.

"Structurally, the middle is down to bedrock," he says, "and the sides are on footings, so the sides settled. It is a 150-year-old building."

In the back corner there’s an old hydraulic freight elevator that will be replaced and you can still see the water tank next to it on the first floor (pictured above). Next to it is the old loading dock door (the doorbell is still there, outside). Further along that same wall, toward the front, is an old walk-in vault, installed by Milwaukee’s Bayley & Greenslade.

I’m a huge fan of the upper two floors because each has a pair of slender, elegant windows in the central bay of the three-bay facade.

"The first floor's going to be our tasting room, and our visitors center," says Hughes. "We will distill up here, too. We'll make all the products that we serve out of here.

"The second floor (pictured above) is going to be for private events. We'll be able to do weddings up there, corporate events, birthday parties. We don't know yet where we're going to be, capacity-wise, but it could be up to 160. The third floor (pictured below) will be office space. We're planning on having the elevator run through the roof, because we want to do a deck. The views from up there are incredible. The roof is actually in great shape.

"We'll have our architect chosen next week and they'll actually tell us what we're going to do with the space."

Hughes and McQuillan are aiming to be open by July, says the former.

"That's what we're pushing for. We have a pretty aggressive schedule once we close. We're making a lot of progress; everything's going really well.

"Last year was our best yet; we get better every year. Hopefully that continues."

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has be heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.