Cheers! It's Bar Month at OnMilwaukee – so get ready to drink up more bar articles, imbibable stories and cocktailing content, brought to you by Potawatomi Casino Hotel and Miller Lite. Thirsty for more? To find even more bar content, click here!

Though the name of this series is urban spelunking, I readily admit, with regret, that I don't get to visit too many actual caves. The crumbling beer caves beneath the old Falk Brewery are one exception.

The beer caves adjacent to the Miller Inn, 3931 W. State St., at Miller Brewing are another. These caves, unlike the examples at Falk on the South Side, however, are open to the public.

The caves, dug into the ground and lined with vaulted brick ceilings served the same purpose: in pre-refrigeration times they offered cool, consistent temperatures required for storing – and sometimes for fermenting – beer.

While the public is allowed – nay, welcomed – into the Miller Caves as part of the company’s popular brewery tour, the current cave, with its bend to the right and then to the left, is just a segment of what was a larger complex of caves.

Here’s the gist of the story ...

Before there was Miller, there was the Plank Road Brewery, owned by Charles and Lorenz Best, who dug the first sections of caves beginning in 1850, using what was the Belgian method of tunneling into soft soil.

First used in Belgium’s Charleroy Tunnel in 1828, the method divided the area to be dug into sections and the central section was always in a more advanced state of excavation in relation to the outer sections. The top sections were completed first, allowing the construction of the supporting vault early on.

The Bests dug their tunnels 62 feet below ground, with 36-inch-thick brick and limestone walls and vaults. They were 15 feet wide and 12 to 18 feet tall.

When, five years later, the Bests sold the brewery to Frederick Miller, the latter continued tunnel construction, completing roughly 600 feet of underground beer storage tunnels by 1885. In here, Miller could store 12,000 oak barrels.

In addition to Miller and Falk, other Milwaukee brewers built caves, too, including Schlitz, which dug underground vaults at 3rd and Walnut in 1850 that could store about 150 barrels of beer, and Gettelman, near Miller, which excavated enough tunnel in 1856 to store about 800 barrels. Other brewers – like Pabst and Blatz – did the same.

According to an internal history penned by a Miller staffer, "The caves were constructed for fermentation, aging and storage of lager beer. The term ‘lager’ is derived from the German ‘lagern,’ meaning to stock or store. Lagering had been practiced since at least the 7th century, when European monks discovered it was possible to store beer in mountain caves possessing a low uniform temperature during the warm spring and summer months.

"The practice of cutting ice from lakes and storing beer in underground cellars or vaults originated in Germany. Following this pattern, beer in the Miller Caves was kept cool with ice cut from local ponds and lakes during the winter. In the summer, sawdust and hay were used to insulate the ice, which turned the caves into a giant refrigerator. In the winter, the caves were sometimes opened to allow cold air to flow in, but the beer was never allowed to freeze."

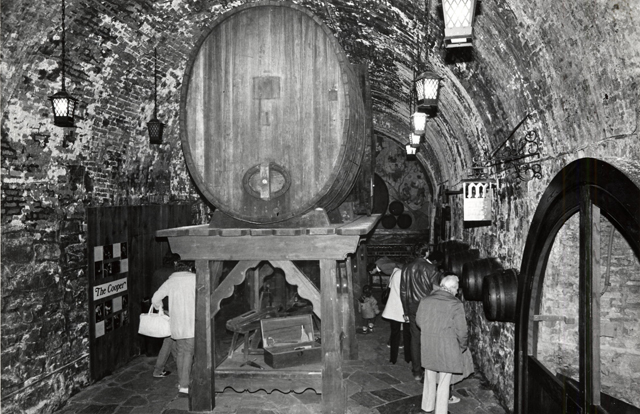

The lager was aged in big wooden tanks and transferred to round or ovular oak barrels bound with iron hoops and coated with a sealer like varnish or pitch. The barrels were stacked horizontally onto skids and the caves were sealed tightly to keep the cold air in.

The lager was aged in big wooden tanks and transferred to round or ovular oak barrels bound with iron hoops and coated with a sealer like varnish or pitch. The barrels were stacked horizontally onto skids and the caves were sealed tightly to keep the cold air in.

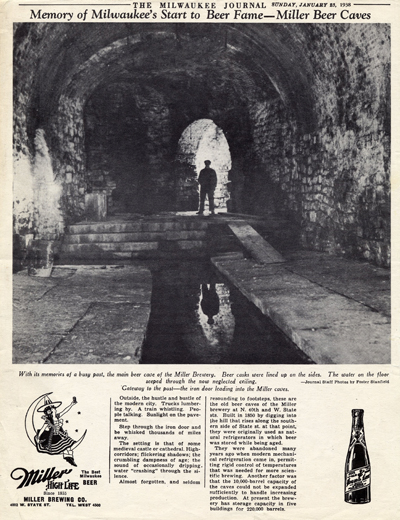

Because mechanical refrigeration began to arrive on the scene at the end of the 1880s and the beginning of the 1890s, the caves became obsolete. Because of that, and the fact that they’d begun to leak, Miller sealed off the caves in 1908 and while it might be a stretch to say they were completely forgotten, they definitely weren’t much discussed for decades. A 1938 advertisement talked about the cave and included a photo of a man standing in one of them.

The caves were thrust back into the Miller Brewing consciousness when, during the construction of an elevator in 1946, a shaft was being dug and the caves were, ahem, rediscovered. The following year, the company began to clean and reinforce the caves and by 1951 – stocked with blankets, potable water and generators – they were set up to accommodate up to 500 people as a bomb and air raid shelter.

"Frederick C. Miller, who was the grandson of founder Frederick J. Miller, was really passionate about these caves," says Miller Guest Relations Manager Kindra Loferski. "So much so that he wanted to host nice dinners in here for his executives, which seemed unheard of to have a nice dinner in a musty cave, but he wanted to do that and he did do that, so he opened the caves back up."

That was in 1952, as part of Fred Miller’s drive to create a brewery tour. Other brewers around the country had been doing such tours for decades – Budweiser, for example, was doing them as early as the 1880s – though Miller may have been the first in Milwaukee to offer them.

"They found coopers' tools in here, so they knew they were doing work on the barrels as things had been stored here," says Loferski. "They cleaned it all up."

Miller restored about a third of the total caves. They covered the old dirt floors with slate, replaced old gas jets with electric lights and added historic displays, much like the little dioramas you can see today.

"When he did open it back up (on Oct. 19, 1953) and start sharing them with people, they had kind of an unveiling and a re-inauguration of the caves, and Liberace was here to sing," says Loferski. "It was a big deal. Fred Miller was really proud of it."

After a series of dinners hosted by Fred Miller, the caves became the tour headquarters in 1954. The space was renovated again in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s and got another facelift in 2008, when acoustic panels were added (you can see them if you look really closely) and a mural with a holographic video program was installed.

Look at the diagram below and you can see some sections that were filled in.

According to a 1991 geological study, some of the tunnels probably failed sometime during the "forgotten" years, 1908-1946, when the caves were sealed. Some tunnels may have begun to fail even before the caves were shuttered. It appears these sections were filled in during the period, 1946-47, that Miller was restoring the caves.

All of the cave openings – except Tunnel G (the current State Street entrance) were sealed off in 1908. The entrance we use today to enter the caves was shuttered with a steel door.

Other cave sections were filled in during the early ‘90s restoration after water leakage began to lead to failure. The spaces were walled off and backfilled with concrete.

Nowadays, when you see tunnel openings in the cave, like one off to the left when you first enter, one on the right side of the main cave just past the fountain and one on the left side at the far end of the main cave, near the mural, they are sealed and the tunnels behind them most likely filled.

"There might have been a small extension out here," says Loferski as we stand just inside the entrance to the caves. "We keep some supplies in here, but it is no longer a tunnel.

"I don't think this was a tunnel," she says of the one facing us as we entered the caves. "I think this was just a façade, because it would have paralleled the bigger cave down there, and I think structurally, it would have been probably difficult to have dug it that close to the bigger one. It looks like a cave extension, and it's made to look like that. It is a nice way for us to display our cooper, because that's exactly what the caves were used for."

To the right of the mural is a cave entrance that is still open, though the tunnel only runs a few yards and opens into a space in the adjacent Miller Inn building.

So, basically, when you’re in the Miller Caves, what you see is what you get.

While there were once tunnels that went fairly deep into the bluff you can see outside, nothing really remains of them, except the sense history and mystery.

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has be heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.