It seems only fitting that a movie called "The Homecoming" would serve as a real-life homecoming of sorts as well. That’s exactly the case for the project’s director Paulina Bugembe, a Milwaukee native who jokes she spent most of her early years being raised by The Movie Channel and HBO.

"When I was a kid, my dad was a huge Schwarzenegger and Stallone fan," she said. "So I watched a lot of action movies as a kid. And then I was also really into "Star Wars" and a lot of fantasy and sci-fi films. I kind of watched everything, to be honest. But it wasn’t until I got older that I started to venture into more thematic, less fantastical stories."

Bugembe was also "a big Japanese animation nerd," which eventually convinced her to study Japanese and even head to Japan, where she worked as an engineer. Unfortunately, the recession hit, and like so many, she lost her job.

"Everyone growing up told me science and engineering, that’s the stable way to go, and here I am, laid off with no job," she recalled.

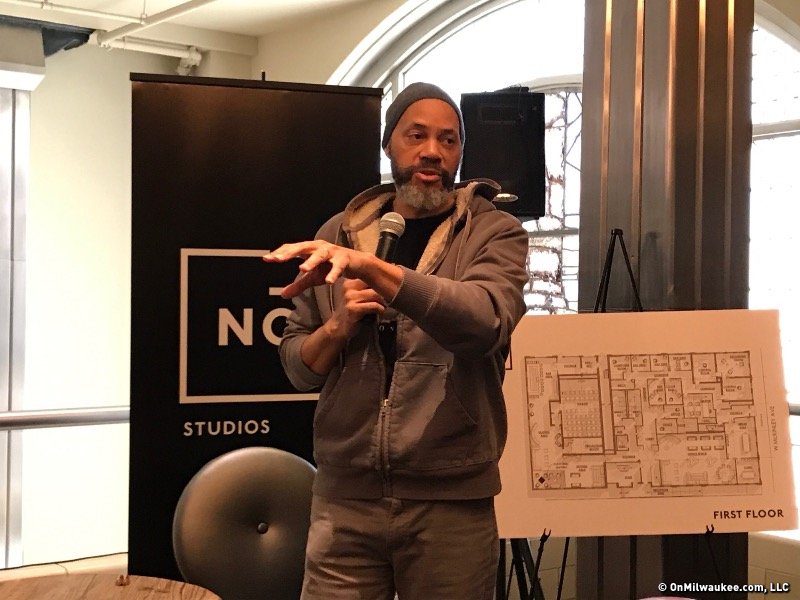

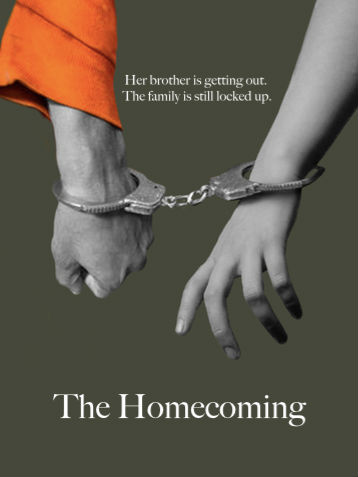

Frustrated and confused, she spent some time in Hawaii working odd jobs, recalibrating her life and finding her way back to one of her earliest passions: filmmaking. So Bugembe headed to L.A., where she’s now working on her Chapman University thesis film, "The Homecoming," the story of a young woman coming home to Wisconsin to plan a welcome home party for her younger brother, who’s just getting out of prison. It’s a very personal project for Bugembe, one that not only brought her back to Wisconsin to film but also came from her own family’s complex and complicated emotional experience with an incarcerated loved one.

The film is still in production – in fact, there’s a GoFundMe page dedicated to raising extra funds – but Bugembe still found time to talk to OnMilwaukee about "The Homecoming," life with prison and the frustrating state of diversity behind the camera in Hollywood.

OnMilwaukee: What about movies really intrigued you and made you want to pursue it as a career?

Paulina Bugembe: I think it’s the power to move people. I’m a crier at movies. I cry, and I laugh … pretty much when the filmmaker wants me to. The fact that movies were able to make me feel things, I think, was probably the biggest draw for me.

On top of that, as I got older and older and more socially conscious and things like that, you can change people’s lives with film. You can introduce people to topics they don’t really know about or understand in a way that’s not so confrontational as just lecturing someone about their belief system and whatnot.

I think that’s the strength of cinema – especially now in the current Hollywood climate of superhero movies. That’s the part that they get now, where you can effectively change people’s minds and get them to think about their lives through entertaining them. Which, to me, is pretty fantastic.

OnMilwaukee: "The Homecoming" is based on your real experiences, correct?

Bugembe: Yes, my younger brother has been in and out of jail. He’s made mistakes, and I think that I relate to the main character a lot because I still have this really strong belief that, when my brother pays his debt to society, he can lead a better life. He can lead the life we all want to lead: the American dream, having a family, having a career. I still believe that.

When a lot of the stuff was going down with my brother, I used to have a more naïve spin on it. I used to beat myself up about if I had just been in Wisconsin – if I hadn’t been living my life in Japan or doing my thing in Hawaii – he wouldn’t be where he is. And I learned the hard way that that’s just not true. I learned that I don’t have control over that; I can’t just fix that. That’s kind of why I wrote the movie – and that’s when I wrote the movie too. I was kind of working through those control issues and that disappointment at the time.

OnMilwaukee: What was that like trying to take those complex emotions fresh at that time and hone them into a narrative and into characters?

Bugembe: It was definitely a process. I’d like to think that in the script we ultimately came up with, Andy is her own person. Yeah, a part of her came from me, and some of the characters, part of them came from my family, but through their help, it became a definitely more universal story. Because everybody has that family member that feels like they’re lost, someone tries to save them, is disappointed and has to learn that they have to find their way. Whether it’s a prison story or an addiction story or a mental health story, the core of the story is universal.

OnMilwaukee: When it comes to issues in America and entertainment, we tend to not like complexity. We like the simple stories and characters, whereas the reality is infinitely more complex than that.

Bugembe: Exactly. And I think what gets missed in that simplification of the issue is how much having someone that you love in prison affects the people outside of prison as well. Gosh, when my mom is asked, "How’s your son?" sometimes she doesn’t even know if she should answer, what she should say – especially if someone doesn’t know if he’s in prison. You become kind of isolated in a way.

We’ve reached out to a lot of groups dealing with people who have loved ones who are incarcerated, and one woman said it really well – and we kind of borrowed part of what she said for the tagline – that we all feel like we’re in prison. We’re treated like criminals when we go visit loved ones in prison; we’re searched and patted down. It’s not like in the movies where you start in a lobby, and you jump cut into the visitor’s room. That whole situation in between, you have cops telling you to turn around, lift your arms up and patting you down; if you’re a woman, it’s almost to the point of violation. And it’s like I’m not the one who’s in prison here; I’m just visiting someone.

There’s a lot of that stuff that doesn’t get shown or people don’t really know about. They don’t know the amount of money it costs to stay in touch with someone who’s in prison. It’s terrible; it’s absolutely terrible. There’s good people out there who have family members in prison that shouldn’t have to go through this either.

OnMilwaukee: Were there any movies or TV shows that came to mind when you were putting together the story and the film?

Bugembe: I would say the biggest one would be "Middle of Nowhere" by Ava DuVernay. I thought she caught a lot of the complex side of it. It’s definitely a different dynamic, in that it’s the relationship between a husband and wife versus a brother and a sister.

But the thing I really appreciated about that film is that she caught the dynamic of the person on the outside who has all the access to this information and is investigating how can they get them out and get them a job and almost their naivety and how that gets crushed by the system. And how the person inside knows how the system works and knows the truth. And that dynamic is so real.

We tend to think, as the family members of the person who is incarcerated, our situation is different; we can figure it out, and we can figure out the system. But it’s only through a harsh reality, similar to the one her character goes through in "Middle of Nowhere," that you realize that the system is rigged. And once they’re in there and they’ve gone through that, it’s definitely not going to be easy when they come out.

OnMilwaukee: It’s interesting you bring up Ava DuVernay because she’s been a key name in this conversation going on right now about diversity in filmmakers, how there are so few female and African-American filmmakers – or at least not the opportunities. Your film is almost entirely female-produced. How is it trying to push forward in that industry that’s struggling to give those voices an outlet on a larger scale?

Bugembe: I think it’s twofold. On top, it’s a matter of people just hiring who they see. A large number of executives are older, white males, and they kind of hire who they know. And the only way to kind of break that, I feel, is to either make your own thing or just do good work. I’m one of those people who lives on the idea of just do good work and something will happen. Someone will take notice. Despite seeing all these numbers saying there’s no women, I’ve been fortunate enough that opportunities have come to me based on my work. So the only thing I can believe in is my work.

The other part of it to me is an access thing. I did casting today, and the lead of my film is a biracial African-American woman. We also have a correctional officer, and the number of submissions that we got … we have over 200, 300 straight white males that applied for this correctional officer that has three lines and one page of dialogue, and we had maybe 30 African-American woman who submitted for, you know, the lead of this movie.

I’m sitting with my producer and I’m thinking to myself: How is this? Part of it is, yes, maybe people they’re only hiring what they know or have seen for so long. But then again, why do I only have 30 people to choose from? Is it an access thing, access to the knowledge of how to start a career in this industry?

So I think it’s twofold, coming from the top but also an access thing. I liken it to surfing. Growing up in Wisconsin, surfing is only really something people do in the movies. It’s like a conceptual thing: No one actually does that in real life … until you move to Hawaii, and you see people doing it every day of their lives. And then you’re like, "Wait, I can do this! I can become a surfer even though I’m from Wisconsin." For me, it’s similar in film and movies. People from Wisconsin or the Midwest or places where they don’t have access to other people who’ve made it, they don’t really believe they can make it.

As much as it is a gigantic cliché to say that one has always had a passion for film, Matt Mueller has always had a passion for film. Whether it was bringing in the latest movie reviews for his first grade show-and-tell or writing film reviews for the St. Norbert College Times as a high school student, Matt is way too obsessed with movies for his own good.

When he's not writing about the latest blockbuster or talking much too glowingly about "Piranha 3D," Matt can probably be found watching literally any sport (minus cricket) or working at - get this - a local movie theater. Or watching a movie. Yeah, he's probably watching a movie.